Tanabata and Taoism

by Tanya Valentine, guest contributor

“True observers of nature, although they may think differently, will still agree that everything that is, everything that is observable as a phenomenon, can only exhibit itself in one of two ways. It is either a primal polarity that is able to unify, or it is a primal unity that is able to divide. The operation of nature consists of splitting the united or uniting the divided; this is the eternal movement of systole and diastole of the heartbeat, the inhalation and exhalation of the world in which we live, act, and exist.” ~ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Tanabata, 七夕, seven-night, which takes place on the seventh day of the seventh month, is one of five seasonal events of the year and is widely celebrated throughout Japan. Because of the discrepancies between the solar and lunar calendars, the marking of the festival varies; in many regions it is celebrated within the standardized Gregorian calendar, the solar calendar, which places the earliest of celebrations on the 7th of July. However, when celebrated as a lunar event, the festival usually takes place during the month of August, notably preceding and, perhaps, preparing for Obon, which is held on the fifteenth day of the seventh month.

Tanabata is also known as Hoshimatsuri, 星祭, Star Festival, and the celebration has become a known as a time for displays of bamboo and tanzaku. Tanabata has come to be largely associated with the tale of the Weaving Maiden and the Cowherd. This story is often directly derived from the legend related to the Qixi Festival from China. As such, in Japan the festival is celebrated in a variety of ways in different regions. In some areas, the festival is associated with praying for marriage and children, in other areas, all manner of activities related to weaving, craftsmanship, and the protection and harvest of crops are the focus.

The folktale of the Weaving Maiden and the Cowherd, which in modern times appears to be at the heart of the Tanabata observance, explicitly outlines the causes and conditions for both the couple’s separation, as well as their desired reunion. It is the tale of these two beings and the aspect of reunion that is the focus here, particularly as it relates to the practices of Neidan, 内丹術, Taoist Inner Alchemy. Neidan is also known as Jindan, 金丹道, the golden elixir. Dan has been variously translated as cinnabar, vermillion, elixir, and alchemy. Elixir may be another way of identifying that is which is sometimes described as ‘Fundamental Nature’.

As a practice, Neidan is concerned with cultivating a variety of physical, mental, and meditative states aimed at attaining the highest form of enlightenment, that is, full immersion in the undifferentiated state of cosmic consciousness. The practices outlined in the Neidan tradition are methodical, they are step by step processes that include a great deal of purification practices. It is of extreme import that no step be skipped lest it leave practitioners unable to navigate the plethora of threshold experiences embedded in the transmutation of energies. These processes include subtle body meditations and astral energy guiding practices that give the practitioner the opportunity to connect, via meditations, with Heavenly and Earthly energies.

Of central importance in understanding the Neidan practices is the Taoist conception of the three vital energies that animate the physical body. These are san-bō, 三寶, three treasures, which are defined as:

Jing – all that we arrive with at birth. It is the life essence that forms our structural and energetic makeup. Jing is intimately connected to our constitutional well-being, to our ancestral lineages, as well as the potential to reproduce.

Chi – identified as the vital organizational force within our body. It carries In and Yō energies, in their various configurations, throughout the body.

Shen – the animating and organizing force at the center of consciousness, what is often referred to as spirit.

These three treasures are closely associated with three areas in the body referred to as dantian. The meaning of the word is variously translated as elixir field, cauldron, furnace, sea of chi, energy center, etc. Three main dantian are located in the belly, the heart, and the head.

Taoist practitioners of Neidan believe that it is essential to learn to cultivate shen, in part, this is done by balancing chi and preserving jing. The preserving, balancing, and cultivating practices come in a variety of forms both external, i.e., Chi Kung, Tai Chi Chuan, Tao Yin, Zhan Zhuang, etc., and internal practices such as Neidan. There are a great number of texts and illustrations that provide instruction on how to preserve, balance, and cultivate the three main energies, the vast majority of which are written in a coded language of metaphor and allegory.

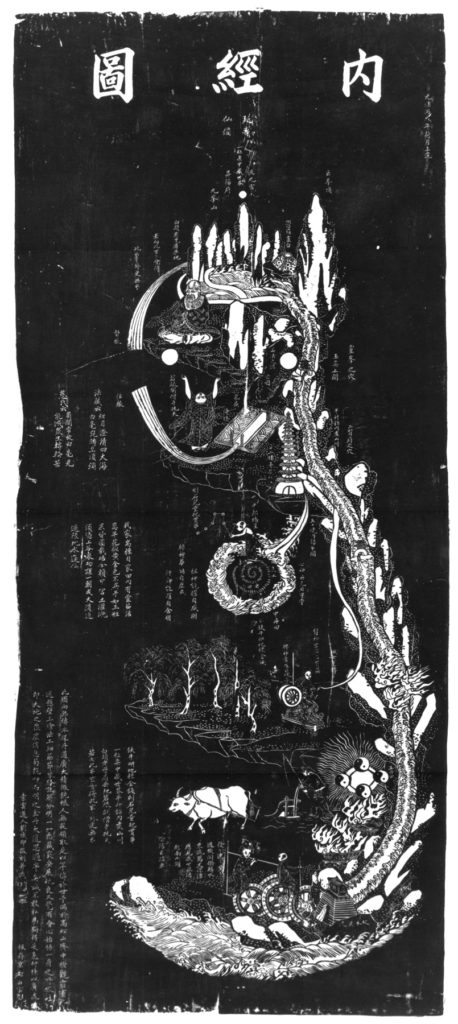

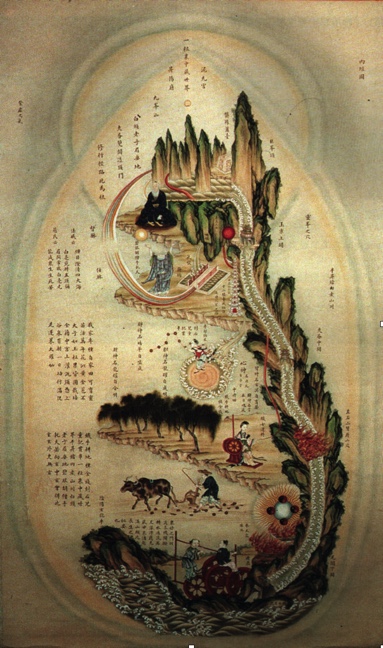

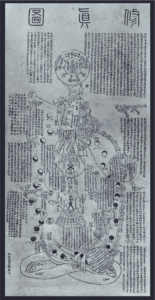

For the purpose of this article as it relates to Tanabata, the drawings known as the Neijing Tu, 內經圖, Chart of the Inner Warp, and Xiuzhen Tu, 修真圖, The Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection will be presented specifically as they relate to the Weaving Maiden and the Cowherd metaphors. Both of these diagrams are known by a number of other names, for example, the Neijing Tu has been variously translated as, Diagram of the Internal Texture of Man, Diagram of the Inner Scripture, Chart of the Inner Passageways, Diagram of Internal Pathways, Chart of the Inner Warp, Chart of the Inner Landscape, and Chart of Inner Luminosity. Likewise the Xiuzhen Tu has been translated variously as, Illustration of Developing Trueness, Diagram of Cultivating Perfection, and the Chart for the Cultivation of Reality.

The exact provenance of the Neijing Tu diagram is unclear, though it is thought that all extent copies are derived from a stele located in Beijing at the Baiyun Guan, White Cloud Temple. The stele was theoretically based on a scroll from a library on Mount Song located in Henan. Mount Song is a sacred Taoist mountain and is host to a great number of Taoist and Buddhist temples. It is notably the home of the Shaolin Monastery where the first patriarch of Chan Buddhism, Bodhidharma, lived and practiced for a time.

The Neijong Tu stele, dated 1886, exists due to a priest named Liu Chengyin, who, having seen it painted on a scroll, became fascinated. He describes his motivation for the stele’s depiction in this way:

“…by chance, it was hanging on a wall. The painting was finely executed… I examined it for a long time and my comprehension grew. I began to realize that exhalation and inhalation, as well as expelling and ingesting, of the human body are the waxing and waning as well as the ebb and flow of the cosmos. If you can divine and gain insight into this, you will have progressed more than halfway into your inquiry of the great Way of the Golden Elixir. In truth, I did not dare not keep this [painting] to myself alone. Therefore I had it engraved on a printing plate for wider dissemination.”

It would appear that most, if not all, modern copies of the image and text are based on the White Cloud Monastery stele. The image provides a full array of instructions and directions for Taoist practices related to both the Microcosmic and the Macrocosmic formulas for the creation of the Immortal Self.

The Diagram of the Inner Warp contains veiled metaphorical and allegorical instructions for a variety of practices that closely align the inner landscape of the practitioner with Nature, Earth, and the Cosmos. The image and accompanying text outline a systematic approach to the inner secrets of the Tao. They function like a map with many layers to guide the practitioner systematically through the varied stages and formulas involved in a plethora of healing exercises, meditations, energy attunements, and guiding of energies. Deeply hidden within the metaphors and allegories are representations of a variety of dimensions of existence outside the everyday constructs of time and space. Imbedded in the depiction of the human body as the universe, are instructions for refining the three treasures (shen, jing, and chi), as well as directions for navigating the inner cosmos so as to bring about unity of the heavens and humanity, and it ultimately draws the practitioner into the experience of ultimate oneness, or, put in Buddhist terms, the eternal unchanging treasure that is Tathāghata.

The Neijing Tu is a diagram of the spiritual approximation of the human form as viewed from the medial plane. Though it is not meant to replicate the physical anatomy, rather it is focused on a spiritual anatomy, there are anatomical markers to help the practitioner navigate the inner landscape. At the base of the spine are a boy and a girl with a Water Wheel. These two beings are representative of the male and female generative principles. Next to the Water Wheel is the Iron Ox, plowing a field. It may be tempting to think of this as the cowherd, but, the text accompanying the image describes this as “the iron ox plows the field where coins of gold are planted.” From an anatomical standpoint, this area corresponds with the digestive tract, one can imagine the furrows of the field are indicative of intestines. In this depiction the Iron Ox is reference to, amongst other things, the energetic channels that must be clear and open so that the water element of the kidneys can be carried up the spine via the breath.

On the chart, slightly above and to the right of the Iron Ox is the Weaving Maid, who is associated with the star Vega, she is spinning breath, life force, and Yin elements together so that they ascend to the upper dantian where these essences again undergo a process of alchemical transmutation. Slightly above the Weaving Maid is the Cowherd, who is associated with the star Altair and is depicted as holding the Seven stars of the Big Dipper while standing on a spiral path that may indicate a Taoist rendition of the shamanistic dance ritual, Yubu, 禹步, Yu the Great’s Paces. Depictions of Yubu can symbolize the practitioner spanning the three realms of Earth, Human, and Heaven in continuity, while the handling of the Big Dipper points to a variety of allegories for spiritual development, as well as teachings regarding the Pole Star.

The Weaving Maid’s thread extends past the Cowherd up the spine to the inner aspects of the skull and the upper dantian where the energies and vital forces it carries are transmuted and refined into rarefied elixir that must cross the Magpie Bridge to travel back to the heart region wherein the Cowherd resides.

On the most basic level, the diagram describes a reversal of energy flow. In nature, water typically flows down and fire rises up, whereas in the beginning stages of Neidan the practitioner is engaged with drawing In/water element forces up the energy channels corresponding with the spine, as well as bringing Yō/fire element forces down into the belly. A full accompaniment of Neidan practice includes a total of nine inner alchemy formulas to cultivate the inner Immortal Self.

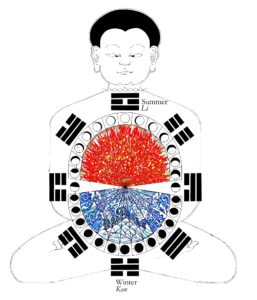

In the Neijing Tu diagram the Weaving Maid is a metaphor for the In aspects and the Cowherd is metaphorically representing Yō aspects. A simplified account of these two beings would show, amongst other things, the alchemical conjunction and harmonizing of In and Yō via reversal of the, ☵, Kan,water, and ☲, Li, Fire elements in the body. With ☲, Li, Fire, below and ☵, Kan, Water above, the cauldron within the active dantian are able to create a steam thought to promote longevity in the body and clarity in the mind. The union, or marrying, of the forces represented by the Weaving Maid and the Cowherd harmonize the practitioner’s opposite poles, so that they may continue on the path towards creating the Immortal Self.

“The marriage of Kan and Li is the secret magical process which produces the child, the new man (person)”. – Lu Dong Pin (Source: “The Secrets of the Golden Flower”, Wilhelm, Richard.)

The coupling of the energies of Kan and Li can take place within the lower dantian (clay cauldron), the solar plexus(iron cauldron), the heart (jade cauldron), as well as in the Crystal Palace in the head. The marriage of these energies in different locations brings about different effects.

Note that in the above image the first quarter and last quarter moons, sometimes called the half moon, lie in the space between Kan and Li, i.e., in this depicition the quarter moons occur over ☳, Zhen, the Thunder and ☱, Dui, the Lake. It happens that the moon is in this, ☳, Zhen, first quarter phase during the lunar Tanabata observance. Within the Taoist conception of the seasons, the seventh day of the seventh moon marks the beginning of autumn. The beginning of autumn roughly corresponds with the figure’s right shoulder and the trigram ☷, Kun, Earth.

When observing the S-style diagram and the beginning of autumn in relationship to the Weaving Maid and Cowherd metaphors, it is interesting to note the correlation of the diagram with another Taoist conception of Neidan practice, this is known as Xiuzhen Tu, The Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection.

On the chart the circle on the right side of the shoulder and neck region bears the following inscription:

“This place is called the Yang Palace, the Heavenly Pillar, the Cavity of the Great one, the Jade Capital Mountain. In front of the sixth cervical lies the Palace of Thunder and Lightning (Leiting gong 雷霆宫); it is the strategic point for ascending to heaven and reaching the Yellow Dragon. Through this inverted path, one can access heaven and penetrate the dark and the subtle. Above and below are unblocked, the water of the Xiang flows in the opposite direction. The yang breath is essential for crossing this very important pass, the door of which is guarded by a Yin divinity. The true breath must reach the Bridge of the Magpies, and suddenly burst through and unlock this pass. Then the Cowherd and the Weaver meet and beget the infant, nourished by the mother’s milk.” (Translation from: “Taoism and Self Knowledge: Chart for the Cultivation of Perfection (Xiuzhen Tu)”, Despeux, Catherine, 2012.)

While not exact in terms of scale, one could imagine the two maps overlaid to show the instruction in the Xiuzhen Tu somewhat coincident with the mark for the beginning of autumn on ‘The S-style Taichi Diagram of Yin-Yang Fishes’.

Regarding the instruction in both diagrams, it is important to know the reference to the Bridge of Magpies has its correlate in the body which is enacted by the anatomic tongue arching up to touch the uvula and, ultimately, move beyond the hard palate to the cavity above the uvula. In Sanskrit this action is referred to as khechari mudrā. In the yogic tradition, engaging in this mudra encourages the rise of kundalini and the retention of the elixir of immortality. The root of the word khecara literally means ‘sky walking’.

From the Taoist microcosmic perspective, the Bridge of Magpies is one of several important metaphors for aligning and catalyzing the union of opposites within the practitioner’s inner landscape so that ultimately the cultivated and transmuted energy in the form of the Elixir of Immortality is able to flow back down into one of the prepared cauldrons. The Magpie Bridge also serves as a metaphor delineating the liminal space between Heaven and Earth, though it is not the only threshold experience the practitioner must activate and utilize.

Through utilizing the formulas as described in Taoist images and texts and following instructions given through direct transmission from a teacher, the inner alchemist becomes immersed in cultivating inner ingredients and purifying the necessary containers so that they can unify and mediate between Heaven and Earth and repeat the original organization process that birthed the Cosmos. As the practitioner advances in the purifying and directing of consciousness via specific meditations, they will experience crossing the typical boundaries of Time and Space. Via a variety of practices that induce threshold experiences, the adept connects with the Stars, the Ancestors, and the Earth essences. Through preserving jing, balancing chi and cultivating shen, a practitioner comes to know the true self as non-local, pure consciousness, or Universal Mind. It is at this point the nucleus of the individual mind fully dissolves and union with the Universal Mind is complete. From the Taoist perspective, this is how the Cosmic or Immortal Child is conceived.

The Immortal Child, who will evolve into the Immortal Self, has as it’s precursor Chi-zi, 赤子, the Red Infant, who is the antecedent, or put another way, the ancestor, to the embryo that, via the nourishment and refinement practices of the Neidan adept, will become the Immortal Child. While the adept is both Mother and Father to the Immortal Self, the Red Infant also has a Cosmic Mother, commonly referred to as Xiwangmu, who is known by a great many names including ‘Queen Mother of the West’ (in some Taoist texts she is thought to be Doumu, 斗母, whose name means ‘Mother of the Big Dipper’, she is one of Chinese mythology’s foundational deities). Xiwangmu is often referred to as the ‘weaver of fate’, has been closely associated with the peaches of immortality grown at her palace on Mount Kunlun, and is often depicted with a host of familiars, primarily tigers, but also nine tailed foxes and three-legged crows. She finds her correlate in Sei-ō-bo, 西王母, of the Japanese pantheon.

It is thought that Xiwangmu may have taught Yu the Great, 大禹, many of his shamanic techniques including the Yu’s Paces, 禹步 which evolved into the practice of Bugang, 步罡, Pacing the Stars of the Big Dipper. The Neidan practices of gathering, absorbing, and metabolizing the light collected in the cup of the Dipper as it rotates is key to the evolution of the Immortal Child.

It is interesting to note that in a commentary titled Shiji Suoyin, 史記索隱, Seeking the Obscure in the Records of the Grand Historian, the Big Dipper is referred to as ‘the throat and tongue of Heaven’, this could perhaps indicate a Macrocosmic equivalent to the Magpie Bridge found in the Microcosmic concept of the Neijing Tu. In his work, The Practice of Bugang, Poul Andersen states “the Dipper is not only the universal outlet of the breath of life, but also the celestial baton which directs the alternations of time. It is seen as commanding the movements of the ‘seven administrators of time’.”

In advanced Neidan practices, the adept combines the flows in In and Yō with certain internal gates, trigrams, and stars in the Big Dipper in order to create particular openings in the cycle of time, liminal experiences which, as Andersen states, are: “a ‘crack in the universe’ so to speak, through which the adept may enter the emptiness of the otherworld.”

“Liminality is in many cultures, including the tearoom, a mystical meeting place of the human and divine worlds.” -Herbert Plutschow (Source: “An Anthropological Perspective on the Japanese Tea Ceremony’, 1999.)

The meeting of human and divine worlds, the material and the empty, is a meeting of polarities. Experiencing the meeting place, the space between worlds, allows the practitioner to burn off the dross of the mundane world and connect to the deeper rhythms of those who came before, to archetypal planes, and the universe as a whole. The container for the experience can be an indoor space such as the tea room, or outdoor setting in nature, but as is shown throughout the Neidan practice, it need not be limited to that which is outside of our own bodies. The body itself is a container, and within the body’s interiority are other containers that support liminal experience. Time and Space operate differently within the liminal, i.e. threshold, experience in part because our consciousness is operating differently. In the threshold experience we are no longer relying on our five senses as the means for perception.

“From the innerness of life one minute, one second is just as long, just as important as one thousand years. The morning glory lasting only a few hours of the summer morning is the same significance as the pine tree rose gnarled trunk denies the wintry frost…. Who then would deny that when I am sipping tea in my tearoom I am swallowing the whole universe with it and that this very moment of lifting my teabowl to my lips is eternity itself transcending time and space?” – DT Suzuki, (Source: Zen and Japanese Culture, Suzuki, DT, 1970).

This crossing between the mundane and sacred, or ephemeral nature of existence, is, in part, what allows for transcendence of ordinary consciousness and ordinary experience.

It is interesting to contemplate Tanabata not only as a story pointing to Neidan, but also to the practices which allow practitioners to travel between the world of form and formlessness, wherein the adept can consciously thin the veils between the worlds in order to more proficiently cultivate threshold experiences. In this way, Tanabata can be seen as a time for creating a ritual space that will magnify the threshold experience (and the cultivation of shen) in order to more easily welcome and commune with departed ancestors (who are pure shen) during the Obon season.

“In the Threshold we experience ourselves as a multiplex. We are both mortal and god, human and creature, wild and cultured, male and female, old and dying, fresh and reborn. We are rough and unmade, not held together. The Threshold is where grain and chaff, beater and beaten, are mixed. More explicitly, the Threshold is where we encounter death and can be renewed and restored through the unleashed primordial powers stored in the structures of the mind.” – Joan Halifax Roshi (Source: “The Fruitful Darkness: A Journey Through Buddhist Practice and Tribal Wisdom”, Halifax, Joan, 1993.)