Lunar New Year and Kagami Mochi

Ga-ran-dō, 伽蘭洞, Help-orchid-cave, set with utensils for the Lunar New Year of the Dragon, 2024. Kake-mono, 掛物, hang-thing, Ryū-hi Hō-bu, 龍飛鳳舞, Dragon-leap Phoenix-dance. Kake hana-ire, 掛花入, hang flower-receptacle, bamboo, by Nishi-kawa Bai-gen, 西川楳玄, West-river Prunus-mystery. Buri-buri kō-gō, ぶりぶり香合, full-full incense-gather. Kagami mochi, 鏡餅, mirror mochi. Ya-hazu gama, 矢筈釜, arrow-nock kettle. Ha-ssoku, 八足, eight-leg, hinoki, 桧, Japanese cypress, Shintō offering stand. Usu-ki, 薄器, tea-container, masu, 升, box measure, calligraphy by Hō-un-sai, 鵬雲斎, Phoenix-cloud-abstain. Mizu-sashi, 水指, water-indicate, ceramic, by Makoto Ya-be, 誠矢部, Truth Arrow-guild. Cha-wan, 茶碗, tea-bowl, ceramic with black glaze by Kuro-da Tatsu-aki, 黒田辰秋, Black-field Dragon-autumn.

Japan follows both the solar and lunar calendars, and observes some events twice. A prime example is the New Year; Shin-nen, 新年, New-year, which is also called Shō-gatsu, 正月, Correct-month. The lunar calendar New Year is Kyū-shō-gatsu, 旧正月, Old-correct-month, which begins on the first day of the first month of the lunar year. Because of the differences between the solar and lunar calendars, the date of the lunar New Year varies from year to year. In 2024, the lunar New Year occurs on February 10. Although the observances and celebrations for the lunar New Year are not as lavish as those on January 1, they follow observances related to the phases of the moon. This is especially important in Buddhism and Shintō.

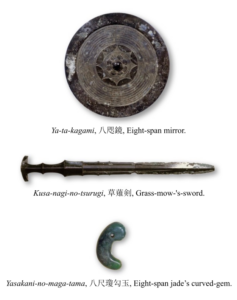

In Shintō, the moon was born of the right eye of Izanagi, a primal deity of creation, and was named Tsuki-yomi, 月読, Moon-count. The sun was born of Izanagi’s left eye, and was named Ama-terasu, 天照, Heaven-brightener. Their younger brother was born of the nose of Izanagi, and was named Su-sa-no–o, 須佐之男, Necessary-help’s-male, and rules the sea. Like many siblings, they disagreed on major issues. Amaterasu was outraged by the destructive nature of Susano-o, and concealed herself in the Ame-no-iwa-to, 天の岩戸, Heaven’s-rock-door, plunging the world into darkness. The eighty myriad gods assembled to coax her to come out, and Uzu-me, 鈿女, Ornament-woman, revealed her gender and danced and chanted much to the amusement of the gods. Curious, Amaterasu rolled back the stone, and Ta-jikara-o, 手力男, Hand-strong-male, held her fast. To appease Amaterasu, the gods gave her a mirror, a sword, and a string of curved jewels. These three treasures became Japan’s imperial regalia called the San-shu no Jin-gi, 三種の神器, Three-kinds of Sacred-implements.

An important element for the New Year observances is the kagami mochi, 鏡餅, mirror mochi, to welcome the first sunrise, gan-jitsu, 元日, origin-sun/day, of the New Year. The kagami mochi is composed of two rounds of mochi, displayed with other objects on a sanbō, 三方, three-directions, which is also san-bo, 三宝, three-treasures. The ‘three treasures’ of the three implements of the imperial regalia, may be represented by the offerings displayed on the sanbō.

In some areas of Japan, the start of the new year is observed on Kyū-shō-gatsu, 旧正月, Old-true-month, which is the first day of the first month of the year, according to the lunar calendar. As with the solar New Year celebration, Kagami mochi, 鏡餅, mirror mochi, is displayed for the Lunar New Year, as a Shintō offering to Ō-toshi-gami, 大歳神, Great-year-god, also called Toshi-toku-gami, 歳徳神, Year-virtue-god. Ōtoshigami is the daughter of Su-sa-no-o no Mikoto, 須佐之男命, Necessarily-assist’s male’s lord, and Kamu-ō-ichi-hime, 神大市比売, God-great-city-like- lady.

As pictured, the kagami mochi display consists of two rounds of mochi, a daidai, 橙, bitter orange, ura-jiro, 裏白, back-white, fern fronds, shi-hō-beni, 四方紅, four-direction-red, a square of white paper edged in red, and the entire arrangement is placed on an offering stand, san-bō, 三方, three-directions, also written sanbō, 三宝, three-treasures.

There are an endless number of styles and adornments of kagami mochi offerings. In a way, it is similar to detailing a prototypical Christmas tree. The essential component is two settled rounds of mochi of different sizes, one larger than the other. If there are standard proportions of mochi, it seems to be a ratio of 10 to 15.

Kagami mochi offerings at Mei-ji Jin-gū, 明治神宮, Bright-peace God-palace, dedicated to Emperor Meiji. These offerings may be regarded as the most authentic, consisting of two rounds of mochi placed a folded piece of wa-shi, 和紙, harmony (Japan)-paper presented on a plain wooden stand, sanbō, 三方, three directions. This simplicity is at the heart of Shintō, and reflects the essential offerings of rice to deities.

Mochi is made by steaming mochi gome, 餅米, mochi rice, sweet rice, which requires water and fire. The steamed rice is pounded into a single sticky mass that is divided into desired portions. Basic Shintō offerings of rice, salt, and water, are called ku-motsu, 供物, offer-things, which are also called shin-sen, 神饌, god-meal. Rice and salt are naturally white, which is another important Shintō aspect.

Paper, kami, 紙, which is usually white, is part of offerings, and protects the sanbō from staining. Some Japanese paper is made with sodium chloride, which is a kind of salt, shio, 塩, and salt is one of the essential Shintō offerings. The rectangular piece of paper is folded in half to make two layers. The two layers are made by folding the sheet of paper slightly askew to show it is in two parts. The aspect of suehiro, 末広, ends-wide, is evoked, symbolic of Infinity in Space.

The offering of kagami mochi can be adorned in countless ways, with the addition of various auspicious and even ‘cute’ alterations turning the mochi into snowmen called Yuki-Daruma, 雪だるま, Snow-Dharma, and other characters. One important addition is tied mizu-hiki, 水引, water-drawn, red and white paper strings around the middle of the two mochi, and tying them into auspicious bows.

The mizuhiki bow establishes a shōmen, which the mochi alone does not have, other than the sanbō stand, which does have a distinct shōmen. The sanbō is also in two parts: the tray and the supporting base.

The Shintō sanbō is most often made of natural, plain wood, hinoki, 檜, cypress, and is composed of a eight-sided tray, o-shiki, 折敷, fold-spread, and supporting eight-sided dai, 台, stand, that has openings on three sides. The side of the base with the seam, toji-me, 綴じ目, join-eye, has no hole, and is the shō-men, 正面, true-face, front, when offered to deity.

The stand is made of wooden sheets cut and bent and joined at a seam secured with mountain cherry bark stitches, which is a process called mage-mono, 曲物, bend thing. A preferred type of hinoki is kuro-be, 黒檜, black-hinoki, Japanese arborvitae, Thuja standishii.

Thin hinoki planks are softened in boiling water for several minutes until they bend easily, then rolled around a cylinder to shape the plank into a hoop. Two thin planks are formed at the same time and are joined into one.

An old container made of magemono is the wappa, 輪っぱ, ring-, a circular wooden ben-tō bako, 弁当箱, distinguish-right box, and lid, food container. It may be the origin of the mage-ken-sui, 曲建水, bend-build-water, vessel for discarded water in a Tea presentation.

Regarding the seam of wooden objects, the rule is ‘maru mae kaku muko,’ 丸前角向, round fore corner opposite. It should be noted that in the kagami mochi display, the ‘front’ of the sanbō is facing away, toward deity so that the viewer is seeing the back of the sanbō.

The sanbō, 三方, three directions, lacquered black with a red interior, calls attention to the nature of directions in the world. Both colors, red and black, are believed to dispel misfortune.

The tojime shōmen of the tray is on the opposite side compared to the base tojime, so that there are two tojime and two shōmen.

Three treasures are represented by holes in three sides of the sanbō. The empty space in the base may represent the noncorporeal Yō principle of the physical In, object, kagami mochi, offered on the tray.

The sanbō, in Shintō, also refers to the three offerings to deity, Umi no mono, Yama no mono, and Hara no mono, which are foods from these three sources. The three Shintō offerings are kome, shio, mizu, 米, 塩, 水, rice, salt, water.

These three offerings are present in Chanoyu in the service of ha-ssun, 八寸, eight-‘inch’, which refers to the measurements of the Shintō inspired wooden tray, ha-ssun bon, 八寸盆, eight-‘inch’ tray, used to serve them. Umi no mono is food from the sea and yamanomono is food from the mountain. The haranomono is the rice transformed into sake served as part of the hassun portion of the meal.

These three offerings are also present in the kagami mochi arrangement, mochi, 餅, rice, from the field, the konbu, 昆布, kelp, from the sea, the daidai, 橙, bitter orange, from the mountain. Other embellishments may include a type of fern called ura-jiro, 裏白, back-white, often written in Katakana, ウラジロ, as well as kushi-gaki, 串柿, skewer-persimmon.

The origin of kagami mochi is obscure, and open to interpretation and depends on the locale in Japan. Although it is an aspect of Shintō, kagami mochi is also offered at Buddhist temples. Some people obtain mochi and related elements at shrines such as I-se Jingū, 伊勢神宮, That-strength God-palace, which is most appropriate as the shrine is dedicated to Amaterasu Ō-kami, 天照大神, Heaven-brighten Great-god, and other deities pertaining to rice and produce. Taken home, the mochi is placed on the kami-dana, 神棚, god-shelf, or any appropriate place as offerings. Ideally, the mochi is offered on the 28th day of the 12th lunar month, because inauspicious date numbers, 29, 30, and 31 are avoided.

In general, it may be that two round pieces of mochi represent two months: the last moon of the year and the first moon of the Lunar New Year. The daidai could be the sun rising on Gan-jitsu, 元日, Origin-day, the first day of the Lunar New Year. The Kanji for daidai, 橙, is composed of ki, 木, tree, and nobori, 登, arise, agaru, 登がる, rise up. It is best to have leaves of the daidai still attached to the orange to show that it is alive. The sun is essential to all life.

The old Japanese word for the color orange was and is named after the citrus, daidai-iro, 橙色, bitter orange-color. The fruit can remain attached to the tree, turning orange in winter and green in summer. Having several generations of fruit on a tree, is emblematic of succeeding generations, even of humans. The name of this citrus fruit lends itself to sacred offerings as it is a homonym for dai-dai, 代々, generation-generation, which is emblematic of longevity and heritage.

The sections, ka-niku, 果肉, fruit-flesh, of the daidai vary in number, although nine sections appear to be an average. Nine is a highly significant symbolic number. The daidai has many tane, 種, seeds, which are relatively easy to germinate and propagate new plants. As with many different seeds, daidai seeds resemble somewhat the maga-tama, 勾玉, bent-jewels, which are one of the three objects comprising the Sanshu no Jingi, the Imperial Regalia of Japan.

While a dai-dai is placed above the kagami mochi, beneath the mochi is a fern called ura-jiro, 裏白, back-white, often written in Katakana, ウラジロ. The Latin name for this fern is Diplopterygium glaucum (Thunb. ex Houtt.) It is an evergreen vining fern and is used widely in Chinese medicine to aid in blood flow, treatment of tumors, fractures, etc. Other uses for this plant include harvesting its fibers for use in making paper and fabric. In southern Japan, the fern is used in making baskets.

The fern grows two fronds at the end of each stem, thus forming a sue-hiro, 末広, ends-wide, which is emblematic of Infinity in Space. The double frond has no fixed location, and symbolically directs blessings both inward and outward. Similarities may be present in the shifuku of the chaire. Some species of fern are used to make cord, the black-dyed, warabi-nawa, 蕨縄, fernbrake-rope, that ties garden fences and wraps seki-mori ishi, 関守石, barrier-guard stone, that block passage in the roji, teahouse garden.

As seen in the kagami mochi displayed in the image above, hoshi gaki, 干し柿, dried-persimmon, are often included in the arrangement. The fruit is a shibu-gaki, 渋柿, astringent-persimmon, that becomes sweet when dried over time. Ten persimmons are strung flat on a skewer, and called kushi-gaki, 串柿, skewer-persimmon, which is placed on top of the mochi. The inclusion of dried persimmons to the kagami mochi offering is often attributed to Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who’s health was improved by eating the dried fruits. It is thought the skewer represents the Ame-no-mura-kumo-no-Tsurugi, 天叢雲剣, Heaven’s-gather-cloud-sword, another object of the Imperial Regalia of Japan.

A kushi-gaki for kagami-mochi is composed of a bamboo skewer with 10 persimmons, divided into groups of 2, 6, and 2 fruits. It is said that the numbers made a phrase, ni-ko ni-ko, naka mutsu, 二個二個中六, two-pieces two-pieces middle-six, which is wordplay on the phrase, ni-ko ni-ko naka mutsu, ニコニコ仲睦, smile smile relationship friendly.

Kushi-gaki, 串柿, skewer-persimmon. In the autumn, millions of persimmons are dried for displays of kagami mochi for the New Year. Groups of eight persimmons on skewers are suspended on two straw ropes secured by two persimmons on each end. This is so that the rope does not slip off the ends of the skewer.

There are many varieties of persimmons, some are eaten fresh, while others are relatively inedible until they are dried and become very sweet. Fresh, sweet persimmons should be evenly round and the four-leaf sepal, kaki no heta, 柿の蔕, persimmon’s calyx, should be quite green and lie flat against the fruit. The shape of the calyx resembles the so-called hishi hana-bishi, 菱花菱, rhombus flower-diamond, the diamond-shape found widely in early Japanese design.

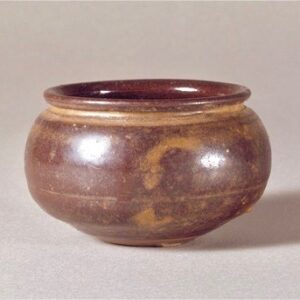

One of the most significant chaire is the ‘Kaki no heta’, 柿の蔕, Persimmon’s calyx, which was brought to Japan from China by Ei-sai Zen-shi, 栄西禅師, Splendor-west Zen-master. It was in this small jar that contained tea seeds that were planted by Myō-e, 明恵, Bright-blessing, at Kō-san-ji, 高山寺, High-mountain-temple, in Kyōto.

Ki-mamori, 木守, tree-protector, is a persimmon left on the tree for a bird to take away and scatter its seeds elsewhere aiding in proliferating the trees. The Kanji for persimmon, 柿, is composed of moku, 木, tree, and shi, 市, city, signifying that it is a planted tree, rather than growing naturally. ‘Ki-mamori’ is the name of a red Raku chawan made by Chōjirō, and named by Rikyū. The chawan was so-named because it was not chosen by any of Rikyū’s followers when they selected chawan made by Chōjirō.

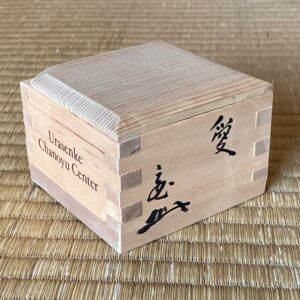

On February 20 is the lunar kagami biraki, 鏡開, when the mochi is broken open and eaten. Another meaning of kagami biraki, is breaking open the lid of a sake barrel, which occurs at celebratory occasions, like the New Year. The masu, 枡, box measure, pictured below, traditionally used to drink sake, is now used as a tea container as seen in the image of Garandō above.

For further study, see also: Chanoyu and the Mirror, Chanoyu and the Orange, Kagami Mochi, and Mochi Pounding for the New Year