Chanoyu and Zen Landscapes

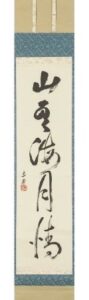

In the realm of Chanoyu, an essential component of a Tea gathering, is a kake-jiku, 掛軸, hang-scroll, that is displayed in the tokonoma. The kakejiku may have calligraphy or a picture in sumi, 墨, ink, drawn with a fude, 筆, brush, on haku-shi, 白紙, white-paper. Calligraphy, sho-dō, 書道, write-way, is preferred, especially when written by a Zen Buddhist priest, whose writings are called boku-seki, 墨跡, ink-traces. The calligraphy is often Zen words or phrases. The Iemoto of families dedicated to Chanoyu are usually ordained Buddhist lay priests, and their calligraphy is deemed equal to that of priests.

For a Cha-ji, 茶事, Tea-matter, in which a meal and tea is served, only the kakejiku is displayed in the tokonoma during the meal, and is replaced by flowers when tea is presented. When first entering the Tearoom, one goes directly to the tokonoma to see what is displayed, and silently bows to the scroll as though it were a teacher who will offer words of inspiration. Thus, the preferred scroll contains Zen words, and the teacher is present only in spirit.

Zen-go, 禅語, Zen-words, are varied and wide, often with expressions that cannot be understood except through deep experience. It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words, but a word is worth a thousand pictures. Mountain.

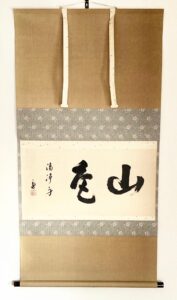

Kake-jiku, 掛軸, hang-scroll, ‘San-shoku Shō-jō-shin’, 山色清浄身, Mountain-form/color Pure-pure-body, one of the 32 physical aspects of the body of the Buddha. Hō-un-sai, 鵬雲斎, ‘Phoenix’-cloud-abstain, XV Oiemoto, Urasenke. Before 1976.

The Kanji for shoku, 色, in the phrase, ‘san-shoku shō-jō-shin’, is also the Buddhist term – rūpa, meaning form; material element; form of existence; etc. Rūpa, ‘form’, refers to one of the five Skandhas (cosmic elements), according to Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism. These elements are eternal cosmic forces and are without a beginning or an end.

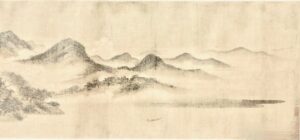

In Zen, there is an expression, ‘San-un kai-getsu’, 山雲海月, Mountain-cloud sea-moon, which represents ma-gokoro, 真心, true-heart, devotion, and i-mi, 意味, mind-taste, significance. Another familiar Zen phrase is ‘Haku-un yū-seki wo idaku’, 白雲抱幽石, white-cloud wraps secluded stone’.

The Chinese and Japanese word for a landscape painting is san-sui-zu, 山水図, mountain-water-picture. And it is true that the picture is usually of mountains or some land feature, and water. However, often clouds or mists are part of the image, and there are paintings of mountains and other land features with clouds. There are paintings of mountains in which clouds are the prominent feature, and these could be called cloudscapes, un-kei, 雲景, cloud-view.

These revered Chinese paintings were collected by the aristocracy in Japan. One such group was the Ashikaga family, and Ashi-kaga Yoshi-masa, 足利義政, Sufficient-advantage Righteous-govern, displayed them at his villa which became Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple. Chinese landscape paintings, tea bowls and other fine pieces were displayed in the Tō-gu-dō, 東求堂, East-request-hall. The largest of the four rooms in the Tōgudō was dedicated to the veneration of Amida: Butsu-ma, 仏間, Buddha-room.

Japan has greatly appreciated Chinese art and culture, and collected many fine works of art, including landscape paintings. The Japanese Kanji for landscape are san-sui, 山水, mountain-water, and a picture is san-sui-zu, 山水図, mountain-water-picture. Another Japanese word for landscape is fū-kei, 風景, wind-view. Because such Chinese works were costly and affordable only by the wealthy, hanging scrolls replaced the image of the landscape with words that implied the landscape. For Chinese Buddhism, the land itself was the manifestation of the Buddha. In Hōunsai’s writing, san shoku, the mountain’s form, the land, is the absolutely pure body of the Buddha, shō-jō-shin. This is the veneration of the world.

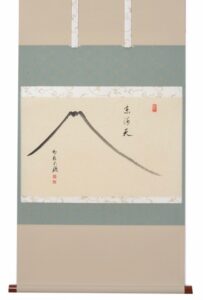

Kake-jiku, 掛軸, hang-thing, ink drawing, Fu-ji-e, 富士絵, Noble-warrior-picture, with calligraphy, ‘Tō-kai-ten’, 東海天, East-sea-heaven, by Ari-ma Yori-tsune, 有馬頼底, 有馬頼底, Have-horse Trust-depth, head priest of Shō-koku-ji, 相国寺, Phase-country-temple, Rin-zai-shū, 臨済宗, Confront-relieve-sect, Kyōto. Photo courtesy of Sen-ki-en, 千紀園, Thousand-history-garden.

Black ink calligraphy on the white paper may suggest that the word is the mountain and the paper is the cloud. The image of Fuji is a kind of cloudscape, un-kei, 雲景, cloud-view.

Fu-ji-san, 富士山, Noble-warrior-mountain, is very near the sea, however, many depictions show the mountain rising above a sea of clouds. Those images showing the sun rising above the mountain are seen from the west of Fuji. The name of the dormant volcano, ‘Fuji’, is thought to derive from an Ainu word for ‘fire’. The word fuji is also written with the Kanji, 不二, no-two, meaning peer-less.

The profile of Fuji-san, is like the Japanese number for eight, hachi, 八, which is derived from geometry and one/eighth of a circle. It is a great symbol for Infinity in Space, sue-hiro, 末広, ends-wide, and emblematic of abundance.

In the abbot’s drawing of Fuji, the white paper may be identified as a sea of clouds. His red stamp in the upper right of the image, may suggest the rising red sun. The calligraphy, Tō-kai-ten, 東海天, East-sea-heaven, identifies the east, where the sun appears to rise from the sea, and ten, 天, also means ‘sky’. Poetic license.

Sacred mountains often have an association with the Buddha. One extremely important mountain in Buddha’s life is Vulture peak, Gādhrakūta, in Japanese, Ryō-ju-sen, 霊鷲山, Spirit-eagle-mountain, is a renowned Buddhist, Hindu and Jain pilgrimage site. It was the Buddha’s favorite retreat in Rajagaha. It’s also said to be the place where he preached his Lotus Sutra, Ho-ke-kyō, 法華経, Law-flower-sutra, and the Heart Sutra, Han-nya-shin-kyō, 般若心経, Carry-young-heart-sutra. Hannya is Japanese for the word Prajna which means wisdom. At a height of 400 meters, it has a panorama view of the land.

The Buddha chose caves and high places for his meditation and preaching. Another Buddhist who chose such locations was Bodhidharma, called Daru-ma, 達磨, Attain-polish, in Japanese.

Kake-jiku, 掛軸, hang-scroll; ink drawing of Da-ru-ma, 達磨, Attain-polish. Stamp illegible. The drawing of Daruma may have been intended to have a Zen priest write some inspirational calligraphy.

It is thought that Daruma meditated and attained enlightenment in Damo Cave in the Shaolin Mountains in China.

The entrance to the Damo Cave faces south, so that when one faces into the cave, they are facing north. Old images of Daruma depict him facing to the right, which means that Daruma would be facing east.

It is said that Daruma left an image of himself in cave; Daru-ma men-peki-ishi, 達摩面壁石, Attain-polish face-wall stone. When a person sits in front of the tokonoma with a picture of Daruma, that person sees themself mirrored as Daruma.

The ideal yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, measures 9 shaku kane-jaku square. The width of the tokonoma, ideally in the north wall toward the east, is half the width of the wall, 4.5 shaku, and the depth is half the width, 2.25 shaku. The total width of the three walls of the tokonoma is 9 shaku. Perhaps the nine shaku may be identified with the nine years Daruma meditated in the cave.

When the Buddha was meditating under the sacred tree, pipal, facing east, he saw Venus rising and he attained enlightenment, jō-dō, 成道, become-way. This occurred on the morning of the 8th day of the lunar 12th month, called rō-hatsu, 臘八, sacrifice-eight. The Kanji, 臘, in China, refers to year-end sacrifices to the gods.

The yojōhan may be identified with both the lunar and solar calendar. The 8th day of the lunar 12th month is in middle of the back wall of the tokonoma where a kugi, 釘, hook, for hanging the scroll is located.

Daruma cave, in Chinese, Da-mo-dong, 達摩洞, Attain-polish-cave, is located near the mountain peak above Sū-zan Shō-rin-ji, 嵩山少林寺, Lofty-mountain Small-grove-temple. This is a prime example of a Buddhist temple that has a san-go, 三号, mountain-name. Sū-zan, 嵩山, Lofty-mountain, is one of the five sacred mountains in China. The temple and cave are located in Dengfeng, Zhengzhou, Henan. At the cave are three stone figures – Daruma and two acolytes.

Below Wuru Peak is the cave in which Daruma meditated for nine years, and the Shaolin Monastery, (Jpn. Shō-rin-ji), 少林寺, Small-grove-temple, in the valley below. Shōrinji, renowned for its kung fu, was established in 495. Bodaidharma arrived from India in 527, and by his example created Chan (Jpn. Zen), 禅, Meditation Buddhism. In China, Bodhidharma is called Damo. The natural cave is called Damo Cave, as well as Nine Year Cave.

San-gō, 山号, mountain name is a title placed before the name of a Buddhist temple. The origin of the temple name is the name of the mountain on which the temple was located. Temples are given mountain names because mountains are objects of worship for the Japanese and are easily associated with Buddhism. In China, Buddhist temples were often built on the tops of mountains, perhaps to be closer to the ‘divine’ realm of deities.

A Buddhist temple does not have to be located on a mountain, but still has a sangō. For example, the Zen temple of Ryō-an- ji, 龍安寺, Dragon-peace-temple, known throughout the world for its stone garden, has the sangō of Dai-un-zan, 大雲山, Great-cloud-mountain, even though it is not located on a mountain, but is does include the word ‘cloud’. There are famous Zen masters who bear the name of the temple where they studied and practiced, and thus they bear the name of the mountain after which the temple was named. A good example is the often-quoted Tang dynasty Zen priest and master teacher, Baizhang Huaihai (Jpn. Hyaku-jō E-kai), 百丈懐海, Hundred-(ten shaku) Heart-sea. He is known simply as Hyakujō, which is the name of the mountain in China where his temple was located.

The founder of a Buddhist temple is called a kai-san, 開山, open-mountain. The ceremonial gate of a Buddhist temple may be called a san-mon, 山門, mountain-gate, as well as san-mon, 三門, three-gate, which is a temple gate that has three entrance ways in the gate. The three entrances are likened to the three ways, san-dō, 三道, that one must pass to gain enlightenment.

Mountain climbers climb mountains because ‘they are there’. Mountain tops can be cold, windy, and with a lack of oxygen making it challenging to simply breathe. Yet, climbers will endure and some perish. It should be remembered that the Buddha, after starving himself to near death, understood that the mortification of the body to enrich the soul is not the way to enlightenment. The two adages ‘No pain no gain’ and ‘There is no joy unless one has suffered’ are fallacies. Babies are joyful. Yes, they cry when hungry and wet. Pain will out. We learn to suffer.

Clouds are mysterious. They appear to be white, but can appear to change color depending on the light. They can be seen, but they have no actual physical form. Water vapor has substance, but one cannot actually hold a cloud in the hand. Fog and mist are the same, without tangible form. Climbers pass through clouds, and may get a little damp from water vapor, but the cloud cannot be grasped. Perhaps an even greater mystery is snow. Falling flakes surely can be felt, but it cannot be fully held until it masses together, when it becomes tangible and can be weighty. It can crush objects. Shoveling snow can be an arduous task. In its ideal state, snow is white, or appears to be. Rain must have seemed truly magical. It is manifested out of the nothingness of clouds. Wind?

There must be forces that cause and create these conditions. Gods? They, too, are invisible. In ancient times, people believed that unseen spirits and animals had mystical powers. Shintō belief deifies the phenomenon, without necessarily depicting them in human-like form, except for certain deities, such as Amaterasu, the sun goddess. Shintō belief holds the view that all things have a divine nature. In early Japan, a mountain was a deity, as were trees, stones, etc. In Buddhist belief, there is a ‘human’-like representation for almost every thing and manifestation.

The actual Gin-kaku, 銀閣, Silver-pavilion, has the formal name Kan-non-den, 観音殿, See-sound, and is dedicated to Kannon. The structure was to be covered with silver leaf to compliment Kinkakuji, 金閣寺, Gold-pavilion-temple on the west side of Kyōto. In the foreground is the unique raked gravel garden called gin-sha-dan, 銀沙灘, silver-sand-open sea.

Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple, is the familiar name of Ji-shō-ji, 慈照寺, Mercy-shine-temple, in Kyōto. It’s San-gō, 山号, Mountain-name, Tō-zan, 東山, East-mountain, is also its geographical location. It was the retreat for shogun, Ashi-kaga Yoshi-masa, 足利義政, Sufficient-advantage Righteous-govern, where he devoted himself to the worship of A-mi-da, 阿弥陀, Praise-increase-steep, and Pure Land Buddhism. He also enjoyed traditional arts, incense appreciation, and Chanoyu. He created the Tō-gu-dō, 東求堂, East-request-hall, which had the first yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, room for Tea.

Photograph of the east side of the Tō-gu-dō, 東求堂, East-request-hall, at Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple, showing the shoji and the outside of the sho-in, 書院, writing-sub temple, alcove, of the yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, Dō-jin-sai, 同仁斎, Equal-virtue-abstain, tearoom, Kyōto.

Within the Tōgudō at Ginkakuji is the Butsu-dō, 仏堂, Buddha-hall, an eight-mat size room with an altar dedicated to Amida. The altar is identified as a Shu-mi-dan, 須弥壇, Necessarily-increase-foundation, which is an adaptation of the more familiar X-form Shumidan. The altar’s key feature is the partial balustrade on the base structure

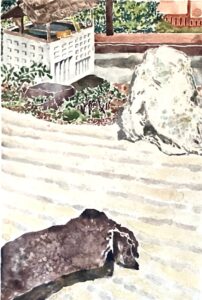

A garden that is identified as a kare-san-sui, 枯山水, dry-mountain-water, has a ground cover of white stone gravel called sha-ri, 砂利, Sand-advantage, gravel. There is an extraordinary coincidence with the word ‘shari’ for gravel, and the word for the relics of the Buddha, 舎利, hut-advantage. Ground covered with gravel is shiki-ishi, 敷石, spread-stone. The white gravel is known as shira-kawa ishi, 白川石, white-river stone.

There have been many changes to the buildings and in the arrangement of gardens of Ginkakuji. There are several gardens at the temple, and two of them are raked gravel. Outside of the Tō-gu-dō, 東求堂, East-request-hall, pictured above, is such a garden with stones and a renowned stone chō-zu-bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water-bowl, where one purifies the hands and mouth before entering the Amida Hall, and the Tearoom which is named Dō-jin-sai, 同仁斎, Equal-virtue-abstain.

Gin-sha-dan, 銀沙灘, silver-sand-open sea, sand garden at Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple, Kyōto. By its name, the sand is likened to an open sea with waves. Historical accounts indicate that the ‘mountain’ of sand was much lower in the past, and has been identified with the moon.

The garden of a cha-shitsu, 茶室, tea-room, is called a ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, which is very different from the raked gravel gardens of Buddhist temples. The roji is a garden with moss covered ground, evergreen shrubs, a pine tree (according to Rikyū), and a meandering path of tobi-ishi, 飛石, flying-stones. It must be made dewy prior to the arrival of guests. Perhaps, the Buddhist white gravel garden is present in the Tearoom in other forms.

Gardens play a significant role in Chanoyu and belief systems, especially in Buddhism, Zen Buddhism. In particular, raked gravel, sha-ri, 砂利, sand-advantage, gardens called kare-san-sui, 枯山水, dry-mountain-water. Expanses of raked white gravel in Chinese gardens are part of park-like gardens with plants, rocks, trees, and paths for walking through the garden. Japanese Zen gardens of raked gravel are meant to be seen and not entered. They are like pictures to contemplate.

Some Zen temple viewing gardens in front of the main hall, are only gravel that is raked with evenly spaced straight lines. The majority of such gardens have one or more rocks that suggest the look of mountains. Some gardens include moss together with the rocks or in areas by itself. Some gardens, such as at Kōtōin in Daitokuji, where the garden is flat and covered entirely with moss, and has a single stone lantern near the center. A few small trees have been allowed to grow. An old drawing of the famed stone garden at Ryōanji shows that once it was covered with moss, but the moss was removed, and the garden was restored to its original graveled surface. Some moss was left near the major stones, out of sentiment.

Gravel-covered courtyards have been a prominent, if over-looked, feature of Shintō shrines. They, too, are featureless, and kept utterly clean of debris. Unlike the Zen raked gravel gardens, the Shintō and Buddhist and imperial, gravel courtyards and expanses are simply swept. Sweeping is endless. One might wonder why the Zen raked gravel gardens have such prominent parallel grooves.

Rocks are quite the opposite of clouds. The white gravel has been chosen in certain belief systems because it is white. Gravel has physical form, is hard and heavy. It can be piled up until gravity pulls it down.

Buddhists meditating at mountain top temples would see other mountain peaks above the low-lying clouds, and, while rare, may have had views looking across a sea. A sea of water, an ocean is seldom colored white, while clouds are, by nature, identified as being white. One of the enthralling aspect of clouds is that they can be of almost any color depending on the light. A richly symbolic aspect of clouds in Buddhism is sai-un, 彩雲, colorful-clouds. In Buddhism, the word ‘sai’ refers specifically to the go-shiki, 五色, five-colors, that represent all aspects of nature.

Assuredly, the raked gravel garden is identified with water, as its name indicates; kare san sui, 枯山水, dry mountain water. The ground of raked gravel gardens is generally flat and many have designs and patterns that imply mass and movement. However beautiful and fascinating the details, it is likely that the original layout was simply flat ground covered with white gravel. Imagination took over to have change. Early exceptions to the flat expanse are the inclusion of two conical peaks that adorn both Shintō and Buddhist gardens. Their identity seems to be open to interpretation.

The I-gyō-shū, 潙仰宗, Flow-revere-sect, was the first of the Tang Dynasty Ch’an Go-ie, 禅宗五家, Zen-sect Five-families. The five families/sects are: I-gyō, 潙仰, Flow-revere; Rin-zai, 臨済, Confront-relief; Un-mon, 雲門, Cloud-gate; Sō-tō, 曹洞, Official-cave; and Hō-gen, 法眼, Law-eye. These are collectively called the Go-zan, 五山, Five-mountains of Zen. Buddhist temples of a particular sect are often organized in groups of five, with one temple as its leader.

The Zen master, Izan, 潙山, was the successor of Baizhang Huaihai (Hyaku-jō E-kai,) 百丈懐海, Hundred-10 shaku (1,000), one of the great masters of Zen, whose concepts and teachings are greatly revered. For example:

A monk asked Hyakujō, “What is the special thing?” Hyakujō said, “Sitting alone on the mountain.” Doku za dai-yū-hō, 独坐大雄峰, Alone sit great-hero-peak.

The two Zen masters Guishan Lingyou/I(Wei)-zan Rei-yū, 潙山霊祐, Flow-mountain Spirit-help, (771-853), and Yangshan Huiji, (Kyō-zan E-jaku), 仰山慧寂, Revered-mountain Wise-tranquility, (807-883), joined together, and became the sect known as Igyō sect. Later, the Igyō sect was absorbed into the Rinzai Sect. Daitokuji is a Rinzai Sect temple. Perhaps the two ‘mountains’ in the raked gravel garden of Daisenin in Daitokuji, pictured above, represent the two founders of the Igyō Sect – Izan, 潙山, and Kyō-zan, 仰山.

Igyō-shū was named after the two mountains, I-zan, 潙山, and, Kyō-zan, 仰山, on which stood the temples of the founders. A unique feature of the Igyō-shū landscape was the creation of the ‘perfect figure’ or ‘circle’ created by the temple complex. One avails oneself of the image of the circle to express completeness and reality.

Kakejiku with calligraphy, ‘San-un kai-getsu jō’, 山雲海月情, Mountain-cloud sea-moon ’s essence, by Hō-un-sai, 鵬雲斎, ‘Phoenix’-cloud-abstain, XV Iemoto, Urasenke.

The passage is from the Heki-gan-roku, 碧巌録, Blue-cliff-record, a collection of Zen anecdotes and lessons, generally classified as Zen-go,禅語, Zen-words. The calligraphy is an interpretation of the landscape painting that represents the actual sacred Chinese landscape.

The Japanese Kanji for cloud, kumo, 雲, is composed of ame, 雨, rain, and un, 云, say; which is also the abbreviated Chinese character for ‘cloud’.

Tō-gu-dō, 東求堂, East-request-hall, Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple, Kyōto. The recessed alcove with a wooden seat is situated so that a person seated on the bench looks westward over the city of Kyōto, which is the location of Amida’s Goku-raku Jō-do, 極楽浄土, Extreme-pleasure Pure-land. The Tōgudō is dedicated to Amida. Note the raked gravel garden at the lower left of the foundation.

The building is set on a traditional Japanese architecture foundation, do-dai, 土台, earth-support, which is generically called a do-ma, 土間, earth-floor. The doma is made of a mortar called tataki, 三和土, three-harmony(Japan)-earth, hard-packed dirt (clay, gravel, etc.) floor; concrete floor. The materials include tsuchi, 土, soil, sek-ai, 石灰, stone-ash, quicklime, and nigari, 苦汁, bittern. Bittern is a concentrated solution of salts (esp. magnesium chloride) left over after the crystallization of seawater or brine, and water.

The entire structure is supported on wooden hashira, 柱, posts, floating on stones called, ne-shi, 根石, root-stone, as well as ke-so ishi, 基礎石, fundamental-foundation stone. The cement-like foundation is white for the appearance of cleanliness, but also emulate the whiteness of clouds. It is as though the structure is floating on clouds. Mountain tops. The sand wall is a curtain to prevent leaves and debris blowing under the raised floor which allows space for the sunken ro.

One of the features of some traditional Japanese official and religious architecture that is part of the foundation is a raised flat area with rounded edges and called a kame-bara, 亀腹, turtle-belly. In Asian mythology, the world is supported on the back of a great turtle that moves slowly through the universe. The turtle / tortoise is said to live for ten thousand years.

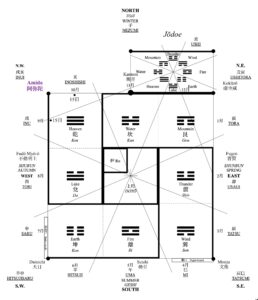

A ki-kkō, 亀甲, turtle-shell, was one of the first objects that was used in Asian divination, ki-boku,亀卜, turtle-divination, and was basis of the I Ching, Eki-kyō, 易経, Change-sutra. The Kanji, 易, was part of Rikyū’s name Sō-eki, 宗易. The Ekikyō is a foundation of Chanoyu, and contributes to the elemental identification of Tea utensils, as well as the yojōhan Tearoom. Aspects of the buildings of Ginkakuji are manifestations of Mount Sumeru.

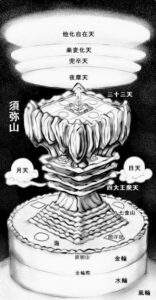

At the center of the Asian world is Mount Sumeru, which is sacred in Bon Religion, Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. In Japanese, it is called Shu-mi-sen, 須弥山, Necessarily-increase-mountain. It is the seat of many deities, and is the home of Indra, king of the gods. In Japanese he is known as Tai-shaku-ten, 帝釈天, Emperor-explain-heaven. The Kanji ten, 天, is used in Japanese to identify and Deva and Devi, male and female Hindu divine beings.

Illustration of Mount Sumeru, Shu-mi-sen, 須弥山, Necessarily-increase-mountain, and its multitude of details with mountains, seas, and temples.

Note: the top of the mountain is above the clouds that are supporting the disc of the sun, 日天, on the right, and the disc of the moon, 月天, on the left.

The illustration is a representation of Mount Sumeru/Shumisen, and highly stylized image depicting the description of Mount Sumeru/Shumisen in the ‘Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Dharani Sutra’. Ksitigarbha in Japan is known as Ji-zō Bo-satsu, 地蔵菩薩, Earth-keep Grass-buddha, guardian of the world until the Maitreya/Mi-roku Bo-satsu, 弥勒菩薩, Increase-rein Grass-buddha.

The hourglass form might suggest the Dai-ten-moku cha-wan, 台天目, Support-heaven-eye.

The earthly manifestation of Mount Sumeru/Shumisen is Mount Kailash (crystal?) in Tibet. It has the form of a pyramid and is nearly always covered with snow. Pilgrims may walk around its base, but are forbidden to climb it.

The diamond-square flat surface at the top of the mountain, which is labelled with the Kanji for San-jū-san-ten, 三十三天, Three-ten-three-heaven (Deva), in the illustration shows the ground divided into 9 squares. This may evoke the Kon-gō-kai Man-da-ra, 金剛界曼荼羅, Gold-strength-world Wide-weed-spread, and the yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, room.

Vimalakirti known in Japan as Yui-ma, 維摩, rope-chafe, who hosted a myriad of deities in his room that was the equivalent of a yojōhan, which is one of the origins of the yojōhan tea room. The illustration depicts a design that may be both a mandala and a yojōhan space. Yuima consulted with Mon-ju, 文殊, Literary-especially, about the seating arrangement for the myriad deities. Monju may be located in the east of the Tearoom where the guests are seated for Tea.

The Tearoom, especially the yojōhan chashitsu, may have physical as well spiritual associations with Sumeru/Shumisen. Examples include the ashes in the fu-ro, 風炉, wind-hearth, and ro, 炉, hearth, of Chanoyu, which will be investigated further.

For further study, see also: Chanoyu and Zen Landscapes Part 2, Furo: Four Sacred Mountains, Kakejiku:Three Forms, and Tokonoma and Imae