Chanoyu in Mid September

The asa-gao, 朝顔, morning-face, morning glory is one of the flowers that is not usually displayed for a Tea gathering because of its association with Sen no Rikyū. It was widely known that Rikyū had grown some fine morning glories, and Toyotomi Hideyoshi asked him for an invitation to enjoy some Tea and the morning glories. When Hideyoshi arrived, there were no morning glories to be seen in the garden. When Hideyoshi entered the Tearoom, he saw in the tokonoma a single morning-glory flower.

There have been many stories about this incident, of which, some are without merit. In Japan, morning glories are grown in pots, as are many plants. Rather than “ripping up all the morning glories from the ground”, Rikyū had put them out of sight and chose one to display in the tokonoma for the Tea gathering. It is thought that morning glories are impossible to cut and put into water in a vase. Untrue. If it were indeed a challenge to do so, the Japanese have figured out how to do it. One thought had the flower still attached to a long vine in the garden and drawn through a window in the tokonoma, and rested on a boat shape container hanging from the ceiling. No! A window in the tokonoma was a later creation of Rikyū’s follower, Furu-ta Ori-be, 古田織部, Old-ricefield Weave-guild, and Rikyū’s grandson, Sō-tan, 宗旦, Sect-dawn, is said to have created the first boat-shaped bamboo hanging flower container.

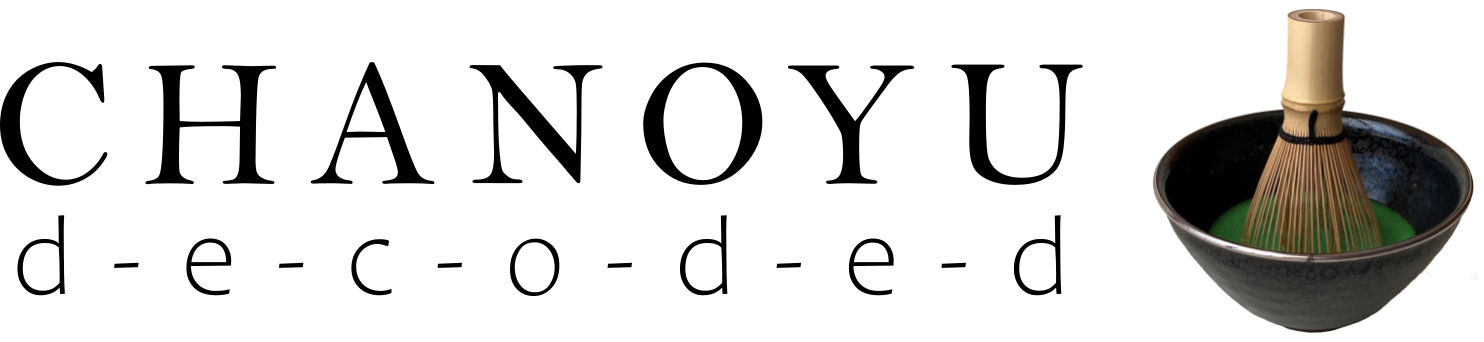

The 9th month is identified with one of the twelve Asian zodiac signs, the Inu, 戌, Dog. Like all the signs, the sign of the Inu is also identified with the years, hours, days, and times. The Buddhist guardian of the sign of the Inu is A-mi-da Nyo-rai, 阿弥陀如来, Praise-increase-steep Like-become.

The fukusa is an essential utensil in Chanoyu as it is used to purify other utensils. Someone may acquire a fukusa for a particular year with a design reflective of the year, such as one of the twelve Asian zodiac animals, and use it for the New Year Teas. Quite often the ‘New Year animal’ fukusa is not used again throughout the year. Perhaps one exception when that year’s fukusa is used in Ro-biraki, 炉開, Hearth-open, held in early November beginning the ro season. A good time to use that year’s fukusa is during a month with the same animal sign, or for a guest who may have been born in that year.

One aspect of the fukusa in the above picture that may seem inappropriate for a Tea gathering not celebrating the New Year are the motifs of shō chiku bai, 松竹梅, pine bamboo prunus. However, these emblems of celebration and renewal are appropriate any time of the year for the proper happy occasion.

The month of September corresponds somewhat closely with the lunar 8th month. However, September is the 9th month, and so, details of the 9th month are to be considered.

From left: Sei-shi Bosatsu, 勢至菩薩, Strength-attain Grass-buddha. Center: A-mi-da Nyo-rai, 阿弥陀如来, Praise-increase-steep Like-become. Right: Kan-non Bo-satsu, 観音菩薩, See-sound Grass-buddha.

The lunar 9th is identified with the Asian zodiac sign of the Inu, 戌, Dog. The Buddhist guardian of the sign of the Inu is A-mi-da Nyo-rai, 阿弥陀如来, Praise-increase-steep Like-become, who is also the guardian of the adjoining zodiac sign of the I, 亥, Wild Boar. The two signs are joined together to create the sign of Inu-I, 乾, Dog-Boar. This Kanji is also read Ken, and has several meanings including Heaven, which seems most appropriate to be identified with Amida.

In the above diagram of the yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, Amida is located in the northwest corner of the room. The monthly worship day of Amida is the 15th with the full moon. As guardian of both zodiac signs of the Dog and Boar, Inu-I, the presence of the full moon of both months is in the middle of the dōgu tatami. This is where the furo is located in the 10th month – for the Tea presentation of naka-oki, 中置, middle-place.

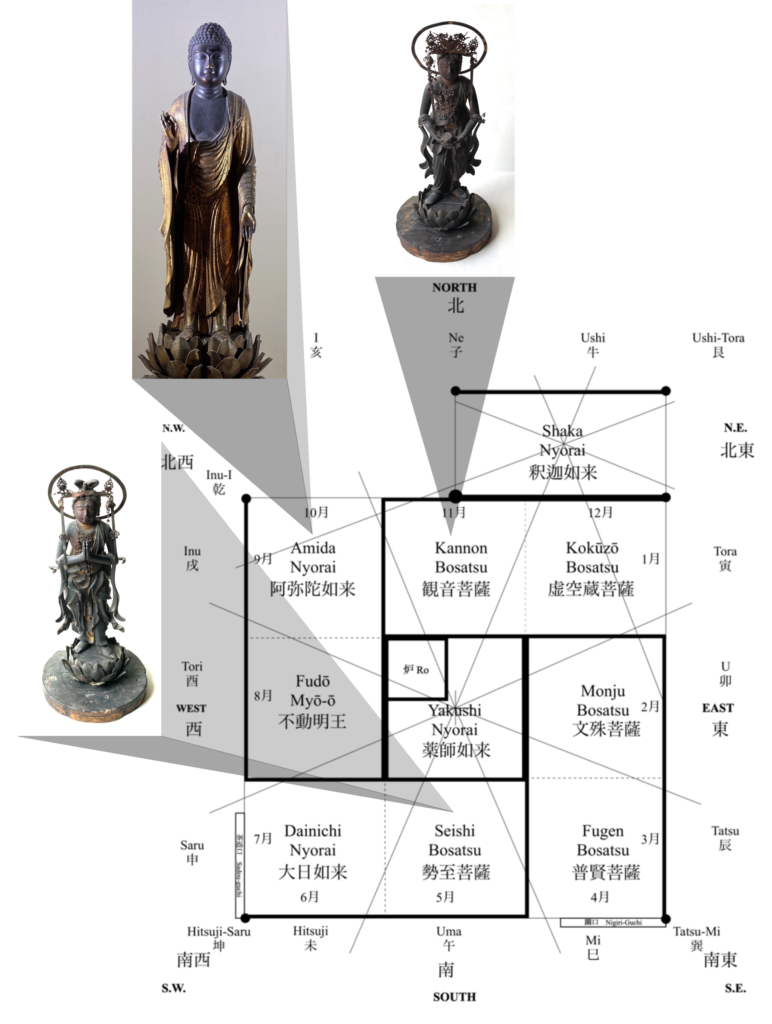

Amida is frequently depicted accompanied by two Bo-satsu, 菩薩, Grass-buddha, Sei-shi Bosatsu, 勢至菩薩, Strength-attain Grass-buddha, to his right, and Kan-non Bo-satsu, 観音菩薩, See-sound Grass-buddha his left.

Rai-go, 来迎, Come-welcome, is the approach of Amida, Seishi, and Kannon. This occurrence is manifest in the yojōhan with the confluence of the Buddhist guardian deities. Amida is in the northwest. Kannon is in the middle of the north, and Seishi is in the middle of the south.

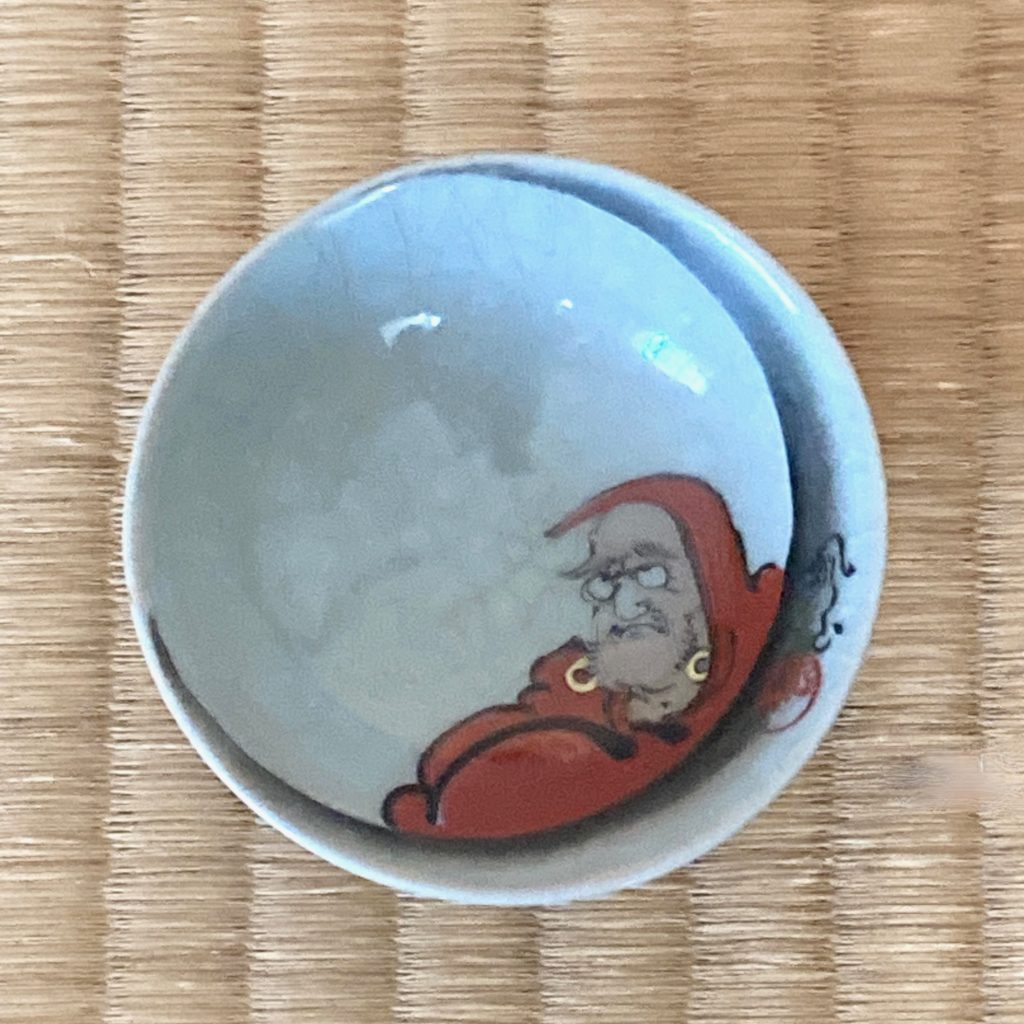

Daruma and the Ninth Month.

On the 21st day of the 9th month in 527, Bodhidharma came to China by boat from India, disembarked at Guangzhou. At this time, Wu-di, 武帝, War-emperor, of the dynasty of Liang, 梁. Beam, was the imperial head of China, and a great supporter of Buddhism. On the first of the 10th month, Emperor Wu invited Bodhidharma to come to the capital city of Nanjing. Their meeting was the circumstance when Bodhidharma was un-willing to respond favorably to the emperor’s claims of his contributions to Buddhism. Perplexed, the emperor asked Bodhidharma, “who are you?” Bodhidharma answered, “Fu-shiki”不識, No-consciousness.

The following quote, alluding to the moon, from Bodhidharma’s Memorial text that was allegedly composed by Emperor Wu: “Vowing to spread the Dharma, he came east from India, planting his staff in China. He expounded the wordless truth, like a bright candle in a dark room, like the bright moon when the clouds open.”

For much of Buddhism’s early history, Indian monks lived and practiced in small groups in the forest. They gathered in larger groups once a month under the full moon to honor the Buddha and Bodhidharma, the ‘blue-eyed barbarian’, may have been among them. Because Bodhidharma is the first Patriarch of Zen (Chan) Buddhism, the sutra that greatly informs that practice, the Shurangama Sutra, is of great importance. In this is the sutra, the Buddha discusses the quandary attached to the ‘finger pointing at the moon’.

The Buddha told Ananda, “You still listen to the Dharma with the conditioned mind, and so the Dharma becomes conditioned as well, and you do not obtain the Dharma-nature. It is like when someone points his finger at the moon to show it to someone else. Guided by the finger, that person should see the moon. If he looks at the finger instead and mistakes it for the moon, he loses not only the moon but the finger also. Why? It is because he mistakes the pointing finger for the bright moon.”

Take dai-su, 竹台子, bamboo support-of, with bronze and iron fu-ro / kama, 風炉 / 釜, wind-hearth; and bronze kai-gu, 皆具, all-tools: a vase-like shaku-tate, 杓立, ladle-stand, holding bamboo hi-shaku, 柄杓, handle-ladle, and metal hi-bashi, 火箸, fire-rods; bowl ken-sui, 建水, build-water [futa-oki, 蓋置, lid-place, hidden in the kensui]; lidded vessel mizu-sashi, 水指, water-indicate. In a formal Tea presentation, the take daisu is used in conjunction with a ha-kke bon, 八卦盆, eight-sign tray, that has designs of the eight trigrams of the Eki-kyō, 易経, Change-sutra.

Perhaps the chasen with fifty tines on the inside and fifty tines on the outside are symbolic of the In and Yō aspects of the Ekikyō. The Ekikyō sticks are sometimes placed in a holder that resembles the handle part of the chasen. In addition, the holder more clearly resembles the shaku-tate, 杓立, ladle-stand, that is part of the set of Tea utensils displayed on the ji-ita, 地板, earth-board, of the dai-su, 台子, support-of, and the naga-ita, 長板, long-board. When beginning a formal Tea presentation, the hibashi are removed from the shakutate, leaving the bamboo hishaku in the shakutate. The one bamboo ‘stick’ of the hishaku in the shakutate, may evoke the one stick of the fifty sticks that is set aside for the Ekikyō divination proceedings. In a very formal Tea presentation, the pair of hibashi are removed from the shakutate one at a time, which might suggest the dividing in half the forty-nine sticks of the Ekikyō.

Zei-chiku, 筮竹, divination stick-bamboo, zei-chiku tate, 筮竹立, divine-bamboo stand, some made of bamboo; also named zei-tō, 筮筒, divine-cylinder. There are variant lengths of the sticks: 1尺(30cm); 1尺2寸(36cm); 1尺3寸(39cm); 1尺5寸(45cm).

When beginning a divination, one of the fifty sticks is set aside, and the forty-nine sticks are divided in half, approximately, as the bundle is of an uneven number. Thus, two groups, one is In and one is Yō, and resemble, in a way, the inner and outer tines of the chasen.

The sticks were originally made of medo, 蓍, yarrow, Chinese lespedeza, divination sticks, and medo-hagi, 蓍萩, yarrow-bush clover; also medogi, 筮, also read zei. The sticks may be made of various materials, predominantly, bamboo. At times, surely, bamboo cooking skewers are used.

Yarrow, a familiar plant in much of the world is Achillea millefolium, commonly known as yarrow. It is a flowering plant in the family Asteraceae. Other common names include old man’s pepper, devil’s nettle, sanguinary, milfoil, soldier’s woundwort, and thousand seal.

Yarrow is an herb. The underground parts are used to make medicine. Yarrow is used for fever, common cold, hay fever, absence of menstruation, dysentery, diarrhea, loss of appetite, gastrointestinal (GI) tract discomfort, and to induce sweating. Some people chew the fresh leaves to relieve toothache.

An ancient group of autumn flowers found in poetry and art are the aki no nana-kusa, 秋の七草, autumn’s seven-grasses. Hagi, 萩, bush clover; o-bana, 尾花, tail-flower, commonly called susuki, 薄, eulalia; kuzu, 葛, arrowroot; nadeshi-ko, 撫子, smooth (hair)-child, pink; ominaeshi, 女郎花, woman-son-flower, patrinia; fuji-bakama, 藤袴, wisteria-culottes; asa-gao, 朝顔, morning-face, morning glory. In the Heian period the asagao was the name given to the ki-kyō, 桔梗, (plant)-stem, balloon flower (Platycodon grandiflorus).

Ki-kyō, 桔梗, (plant)-stem, balloon flower (Platycodon grandiflorus), Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Right: kikyō buds about to open.

The kikyō and asagao were often used interchangeably for both the morning glory and the balloon flower. The kikyō was mentioned in the poems of the Manyoshū, and the morning glory known today was imported to Japan from China in the later Heian period. In the Genji Monogatari, The Tale of Genji, it said that the baby’s mouth was like an asagao that was about to open, which is surely like the ball-like bud of the balloon flower / kikyō. The word kikyō has an age-old homonym, 帰京, ‘return to-Capital’. The kikyō is the subject of many poems in the 8th century, Man-yō-shu, 万葉集, Ten thousand-leaves-compilation.

The mouths on the tigers differ, as the one on the right is open, a-gyō, 阿形, praise-form, and the one on the left is un-gyō, 吽形, ‘mm’-form; and manifest the Hindu and Buddhist primal sounds of aum. This all-encompassing sound is an Asian aspect that has its equivalent to the western alpha to omega, which approximate the same primal sounds. Note that the tiger’s closed mouth is in the shape of the Greek letter omega, Ω. I was at an advanced age when I realized that omicron and omega were, in actuality, o-small and o-big.

Yoga teaches that the ‘ultimate sound’ word aum or om is made of three characters. The first character is om, 唵, which is identified with Dai-nichi Nyo-rai, 大日如来, Great-sun Like-become, who is the universe made manifest. The word, 啞, is identified with A-mi-da Nyo-rai, 阿弥陀如来, Praise-increase-steep Like-become, the Buddha of the western Goku-raku Jō-do, 極楽浄土, Ultimate-pleasure Pure-land. The word, 吽, is identified with Fu-dō Myō-ō, 不動明王, No-move Bright-king, who is the wrothful manifestation of Dainichi. In the diagram of the yojōhan, the locations of Dainichi and Kokūzō are in opposite corners of the room.

The character om, 唵 is composed of mouth and cover, for the sound of aum from a closed mouth to begin to open the mouth to utter the only sound an open mouth can speak. The character, a, 啞, is composed of mouth and follow, for the sound change from ah oh uu. To closing the mouth to intone the character, 吽, is composed of mouth and ox, for the sound of mmmm.