Furo: Style and Form

Water for making tea is heated in a kettle that is heated over a charcoal fire set in a hearth. The hearth was a standard open square in the floor called an i-ro-ri, 囲炉裏, surround-heart-inner, filled with ash and various implement to support different vessels, which were also hung above the fire. In Chanoyu, the hearth was called a fu-ro, 風炉, wind-hearth.

The earliest form of kama was supported directly on the furo. The kama of the Ki-men-bu-ro, 鬼面風炉, Demon-face-wind-hearth, has a quarter-round flange called a hane, 羽, wing, sits on the furo atop an upright perforated collar called a koshiki, 甑, [wok] ring support. Such furo are also called kiri-kake, 切掛, cut-hang, and kiri-awase furo, 切合風炉, cut-together wind-hearth.

Shaku: measurements in traditional Japanese arts and crafts are taken with two bamboo measuring sticks called mono–sashi, 物差, thing-distinction. These two rulers are both called shaku, 尺, span, and are different lengths. They are part of a metric system, with each unit divided into tenths: one shaku divided into 10 sun, 寸, 10 bu, 10 分, rin, 厘. The two shaku are kane-jaku, 曲尺, bend-span, which is equal to 11.93 inches, and kujira-jaku, 鯨尺, whale-span, is equal to 15 inches. The length of the kane-jaku is 8/10 the length of the kujira-jaku. They relate to each other 8:10, which may be identified as ya-ta, 八咫, eight-span, as with the sacred Shintō Ya-ta Kagami, 八咫鏡, Eight-span Mirror, which is symbolic of infinite vastness.

The full height of the furo/kama from the bottom of the furo to the top of the knob of the lid of the kettle is 9 sun kujira. The height of the furo by itself is 5.8 sun kujira; the furo height from its bottom to its shoulder is 4.8 sun kujira. The height of the kama to top of the knob is 4.4 sun kujira. It is as though the koshiki is part of the kama, and that the kama/koshiki ring is sitting atop the shoulder of the furo.

The relationship between the heights of the furo and the kama is 10 to 9. The relationship of 10:9 echoes the full height of the furo/kama of 9 sun kujira. The height of the kama from its bottom to its rim is 3.7 sun kujira, and it relates to the height of the furo from its bottom to its shoulder is 4.8 sun kujira, their relationship is 8 to 10. The number eight is symbolic of Infinity in Space.

From the kama bottom to the bottom of the hane is 1.4 sun kujira. The height of the kama from bottom of hane to the top of the knob is 4 sun kujira. The relationship between the full height of the furo of 9 sun kujira, and the kama from hane to the top of the tsumami is 4 sun kujira, and the furo is 5 sun kujira. The ratio is 4:5, which is also 8:10, that can be identified with ya-ta, 八咫, eight-span, like the sacred Shintō Ya-ta Kagami, 八咫鏡, Eight-span Mirror, symbolic of infinite vastness.

One of the early forms of the open bowl furo, which was inspired by Rikyū, is the mayu buro, 眉風炉, eyebrow wind-hearth. This deep bowl has upright walls with a continuous circular rim and an oblong hi-mado, 火窓, fire-window, at the shō-men, 正面, true-face. There is no opening at the back. The himado, by its name fire-window, may have been intended to be the opening for putting in wood to stoke the fire in the hearth without removing the kama.

The portable brazier used in Chanoyu is called a fu-ro, 風炉, wind-hearth. The furo supports a kama, 釜, kettle, which contains water that is heated by a wood or charcoal fire within the furo. A furo is essentially a portable bowl made of fireproof material that is intended to hold a sumi-bi, 炭火, charcoal-fire, and therefore may also be called a hi-bachi, 火鉢, fire-bowl.

The single most important difference between the furo and the hibachi is that the furo has an opening in the side of the bowl called a hi–mado, 火窓, fire-window. Some hibachi are wooden boxes with metal or plaster liners and may be fitted with other containers and drawers. Hibachi have been part of Japanese culture thousands of years. The common hearth for heat and cooking historically is a four-sided opening in the floor filled with a bed of ash, and called an i-ro-ri, 囲炉裏, enclosed-hearth-inner.

The hibachi is intended to supply a fire for general warmth, and may be fitted with a support for a kettle for hot water or a vessel for cooking. The hibachi is made of metal or ceramic and wood that is fitted with a metal liner. The hibachi may be filled with a bed of ash, hai, 灰, to support the fire which is usually made of wood or charcoal, sumi, 炭: sumi–bi, 炭火, charcoal-fire. In the hibachi, smoothing and leveling the ash is called hai-narashi, 灰均し, ash-level, which is accomplished with a flat metal spatula with a straight edge. A variation has teeth to make raking scored lines.

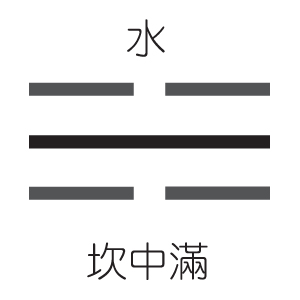

Chanoyu has been influenced by various traditions such as Buddhism and Shintō, including divination which has its origins in Taoism. The most familiar way of divining is the I Ching, which I found intriguing when I was in high school.

The I Ching in Japanese is the Eki–kyō], 易経, Change-sutra. The Ekikyō has various signs, one of which is called a ke, 卦, divination sign, which in English is called a trigram because it is composed of three lines. There are eight signs, hakke, 八卦. In the center of the ash bed in the furo, is drawn one of the eight trigrams, Kan, 坎, pit or hole, which is the sign for Water. In the Old Arrangement of the eight trigrams, Kan is located in the north, and therefore, its presence in the furo, establishes that the furo is ideologically located in the north. When the teishu sits in front of the furo, the teishu is facing north.

There are many kinds of supports for pots and kettles that are most often made of iron or other strong metal, as well as ceramic, and are set in the ash bed. A common support is a trivet called a go-toku, which consists of three posts attached to a ring. The gotoku is used with either the posts or the ring upright. Vessels used with the hibachi have handles to easily move them, and to allow arranging the charcoal fire with hi-bashi, 火箸, fire-rods.

In Chanoyu, a kettle/kama is supported on an upright collar of the furo, or is set on a gotoku. It is believed that the furo and kama originated in China, however, there appears to be no survivors from the past resemble the typical ancient Japanese furo. Furo/kama are known primarily in Japan, where they have existed since the 13th century. The furo is essentially a wide sphere with an opening at the top, and is raised on three feet. Earliest examples where made of iron, tetsu, 鉄, and often were used in Buddhist temples, and were quite large compared to later furo/kama. To this day, furo are made in iron, bronze, and other metals, ceramic, and wood.

The earliest furo had a form that supported an iron kama, kettle, called a kiri–kake bu–ro, 切掛風炉, cut-hang wind-hearth, as well as called kiri-awase bu-ro, 切合風炉, cut-join wind-hearth. [See picture at top.] These furo have an upright collar called a koshiki, 甑, that supports the kama. This is found in modern times, where a round bottomed wok sits on a ring collar over a fire. The term koshiki refers to an upright circular band or collar that is present on kama as well as furo. In some early continental metal and ceramic vessels, the koshiki have small perforations for the passage of air or steam. The furo has larger openings bowl at the front and back called hi-mado, 火窓, fire-window, that along with the koshiki supply air to the fire, that may be the sources of its name fu ro, 風 炉, wind hearth. These openings allow smoke to escape from a wood fire, whereas charcoal gives off very little smoke if fired correctly.

The form of the furo/kama may have been inspired by the bottle gourd. The familiar form of the furo/kame is unusual, in so much that there are devices that do the same thing, heat water. The bottle gourd is one of the most important sacred symbols in Taoism, as it represents heaven and earth, water and food, water, and fire. The Kanji for hyō-tan, 瓢箪, has the Kanji for gourd, hisago, 瓢, which is a gourd for drinking water, and the Kanji, hako, 箪, which refers to a container for eating rice. The ideal Taoist life was to have a container for water and a container for food – rice. The form of the furo/kama could be almost anything, so its similarity in form to the bottle gourd makes it seem more profound, and unites Tea with Taoism, and not Zen Buddhism alone.

The himado of the furo has many different shapes. Some are floral, some resemble fangs.

Ka-tō-mado, 火燈窓, fire-lamp-window, also ka-tō-gata, 火燈形, fire-lamp-shape.

Kō-za-ma, 香狭間, incense-narrow-space. Openwork in construction is called sukashi, 透. A furo with a himado in the shape of a lotus would be symbolic protection against fire, as the lotus is a plant that grows only in water.

Kō-za-ma, 格狭間, style-narrow-space, flamboyant style of architectural ornamentation that may be an opening or relief design that resembles an opening. This design was part of the structural base of Buddhist furniture and sculpture. The motif is generally low and wide and has a symmetrical s-curve and geometric elements, with a point at the middle of the top. In essence, the design appears to be the cross-section of a lotus flower, ren–ge, 蓮華, or hasu no hana, 蓮の花, lotus ’s flower.

The lotus flower and leaves are essential design motifs in Buddhist art and design, as it is upon a lotus that one is born into Buddhist paradise. This design is present in several display stands used in Chanoyu: Fukuro Dana, 袋棚, Bag Shelf, also called Shi-no Dana, 志野棚, and Rikyū Fukuro Dana, 利休袋棚, Jō-ō Mizu-sashi Dana, 紹鴎水指棚, and are the basic structure of the Kō-rai Dai-su, 高麗台子, and Kō-rai Joku, 高麗卓.

The opening of the himado seen together with the symmetrical openings in the koshiki may evoke the appearance eyes, me, 目, above an open mouth, kuchi, 口, resembling a face, kao, 顔. This is true of many kiriawase buro, so that it may have been an intentional design. If this is so, what creature does the face represent? The same could be true of the openings at the back of the furo, if with a smaller mouth.

With certain furo, there is between the two ‘eye’ openings in the koshiki a symmetrical cluster of small openings that may appear to be a kind of flower, hana, 花. In some models, there are six openings around a single opening. Although anatomically incorrectly located, it suggests a nose, hana, 鼻. Perhaps it is a suggestion of wordplay on hana, nose, 鼻, and hana, flower, 花.

The earliest and most familiar motif of the tsumami of the kama no futa is the ume, 梅, Japanese apricot, that is used identified as ‘plum.’ Ume flowers have fiver round petals, not six as in the usual openings in the collar of the furo.

If indeed holes in the koshiki allude to a flower, is a particular flower implied? There are a number of flowers that might be identified: ume, 梅, Japanese apricot, kiku, 菊, chrysanthemum, tessen, 鉄線, iron wire, sakura, 桜, cherry, hō-sō-ge, 宝相華, treasure-aspect-flower, etc. As the openings of the furo are intended to allow smoke and incense to escape, perhaps these small openings in fact are intended to represent fragrant flowers.

It is thought that the hōsōge is not intended to be a specific flower, although it does have its origins in the middle east and is found in Persian fabrics, lacquerware, metalwork, etc. This floral motif has variously four, six, or eight petals, often with a prominent center.

If the himado represents a mouth, could the mae–gawara, 前瓦, fore-tile, which is located directly behind the himado opening represent a tongue? In general, the maegawara is white ceramic, but for some iron furo, the maegawara is red ceramic. Why the difference? The maegawara is believed to have originated in the kawarake, a shallow saucer from which one drinks o-mi-ki, お神酒, hon.-sacred-sake, at a Shintō shrine. The kawarake is imbued with some sanctity. After one use the kawarake is discarded and is often broken, which is one reason why the maegawara is not a complete circle. Some Chinese lion incense burners, when depicted in color, have the tongue colored red, which relates to the red maegawara in certain furo. Even though the maegawara may not represent a tongue, as having been a vessel for drinking omiki, it does come into contact with the mouth.

Shita-gawara, した瓦, (down / tongue)-tile may relate to the mae gawara, 前瓦, fore-tile: shita may be wordplay. Before the ash is put into the furo, a round tile is placed in the bottom, and is called soko-gawara, 底瓦, bottom-tile.

Most important is the large furo and kama, which became obsolete when Tea, Chanoyu, began to be presented in a room that had tatami floor covering. The huge furo was too large, but the large kama was treasured and could not be abandoned. The ro was formalized to accommodate the temple’s large kama. The furo was not completely neglected, but was used in the 10th month when it was placed in the center of the tatami, and a slender mizusashi was set to the side. This style of Tea presentation is called naka-oki, 中置, middle-place. By placing the furo in the middle of the tatami, it is like the kō-ro, 香炉, incense burner that is placed in the middle, as it is on a Buddhist altar.

Copies of the haggard furo usually retain the bridge of the himado and the demon-mask lugs and rings. The intention is to retain the characteristics of the Buddhist temple furo. It should be remembered that the 10th month in Japan is called Kan-na-zuki, 神無月, God-less-month, when all the Shintō deities assemble in Izumo. However, the Buddhist deities remain in their shrines and temples, so that perhaps the center placement of the furo, in which incense is burned, enhances the Buddhist atmosphere.

The old large temple furo, like the kama, was made of iron, and iron rusts and falls apart. The furo was a kiri-kake buro and in time might have lost part or all of its koshiki collar and could no longer support the kama. The kama, too, may have lost part of the hane or flange that rested on the rim of the koshiki. Such a broken down device was ideal reflecting the decline of autumn, and was called a yatsure bu-ro, 窶風炉, timeworn wind-hearth.

Because the furo could no longer hold up the kama, it needed a support for the kama, so a gotoku trivet was used. It was set in the ash bed of the furo, and a smaller kama was set on it. This began the want for a more attractive ash bed in the furo. Because the Japanese appreciate the distressed look of the yatsure buro, it has been copied numerous times, and made to appear to be old. Although in ruins, it still has enough life to supply a fire to heat water for tea. The openness of the yatsure buro may have inspired the creation of the open furo, such as the mayu buro, in that it requires a gotoku.

It is believed that the furo and kama originated from incense burners, kō-ro, 香炉, and the furo is also an incense burner as it is the custom to burn byaku-dan, 白檀, white-sandalwood, in it. Many kōro are in the form of a lion with an open mouth for the fragrance to escape. Perhaps also related to the furo with its three feet, may be the three-legged frog, a symbol of wealth and immortality beginning in China. In Japanese, frog is ga-ma, 蝦蟇, shrimp-toad, and kaeru, 蛙, frog. A popular image found in incense burners is the mitsu-ashi no kaeru, 三足の蛙, three-leg’s frog.

There are pairs of lugs on both sides of the furo as well as on the sides of the kama. The kan of the kama are detachable [See introduction picture of kan on the kama], whereas the kan of the furo are attached although free to be moved, and are called furi-kan, 振鐶, swing-metal ring. The kan are intended to be used to move the furo as well as the kama, although this activity is to be avoided when moving the furo, as the kan may be damaged due to its heavy weight. The furo should never be moved when the kama is on top of it.

An early variation of the kirikake buro is the ki-men fu-ro, 鬼面風炉, demon-face wind-hearth. The furo has ring handles on the sides that are intended to move the furo. The metal rings, kan, 鐶, are attached to the furo by lugs that are called kan–tsuki, 鐶付, metal ring-attach. The form and style of the kantsuki varies greatly from simple geometric form, or elaborately detailed heads or faces. The most frequent name for this style is ki–men, 鬼面, demon-face/mask.

The motif of an animal head or face holding a ring in its mouth is an ancient model seen in many different cultures. Some are purely decorative, while others function as devices to carry the object. In many cultures, the animal is a lion, however in China and later in Japan, the face may be a stylized “demon,” dragon, bird-like, etc.

The word “demon” can be confusing to some people. The character, 鬼, has several interpretations. In Buddhism, there are two fierce warrior type humanoids with frightening faces at the gates of temples that guard the entrances and frighten away non-believers. This pair of beings are the Ni-ō, 仁王, Benevolent-kings. Their grimacing faces resemble some of the ‘demons’ of the kimen.

There are other faces that do resemble lion masks, and these appear on countless incense burners and other objects of Asian art. These creatures are not necessarily lions. They may be one of the nine sons of the Dragon King in Chinese culture: Ryū–sei Kyū–shi, 竜生九子, Dragon-born Nine-child.

In Japanese culture, and that influenced by China, there are very few creatures that hold rings in their mouths. Such a creature is the Chinese inspired ninth son of the Dragon King called Shō–zu, 椒図, Mountain ash-plan, or Pepper-picture. Although his beast face is somewhat lion-like, his full form is like a frog’s. Other creatures that are associated with Shōzu include, spiral shellfish, clams, and mussels. He likes things closed, and forbids others to enter, therefore holds in his mouth the ring of the gate. Frogs and shellfish are creatures associated with water, which acts as a protection against fire, and appropriate for a fire bowl.

The door of a gate may have a metal ring that hangs down from a lug, and may be intended to be a knocker to rap alerting those inside of one’s presence. Perhaps the furo’s upright ring is meant to show that it is not to be used, as no one is allowed in. This would be in keeping with the Yō aspect of the furo, that it can not be entered. The hanging rings of a mizusashi may indicate that they can be used to summon and therefore enter, which is in keeping with the In, receptive aspect of the mizusashi.

When there is a fire in the furo, the kan are raised up and leaned against the shoulder of the furo. When the kama is removed from the furo, the kan of the furo are lowered to hang down. Hanging kan manifest the negative, In , 陰, principle, while kan that are upright manifest the positive, Yō, principle. Some formal style mizusashi also have kan that are made of the same material as the mizusashi. The kan of a mizusashi are left hanging. The In and Yō nature of the kan are in accord with the nature of water and fire. Water is a prime manifestation of In, as Fire is a prime manifestation of the Yō principle.

The Nine Sons of the Dragon King are more prominently associated with a temple bell, bonshō, 梵鐘, Buddhist-bell, also called tsuri-gane, 釣鐘, hanging-bell. Some bells have a dragon-like form, ryū-zu, 竜頭, dragon-head, loop to suspend the bell. Designs on some bells include fields containing nine bosses, which may be identified with the Nine Sons. The temple bell resembles somewhat the kama of Chanoyu, and there are kama which have the appearance of a temple bell.

The furo requires openings to allow air to fuel the fire within. As the objects were created to be well-made and refined in appearance, the air openings were made with elegance and were somewhat symbolic in design. The principle front opening was established to correspond with one of the three feet and thereby identifying it as shō-men, 正面, true-face. This opening is called the hi–mado, 火窓, fire-window. The back of the furo has the other two supporting feet and an air hole that is smaller than the front opening. The designs of the koshiki openings vary, but suggest floral, wave, and geometric patterns.

A key development in the form of furo was the loss or the rusting away of the koshiki of ancient braziers, which made it impossible for the furo to support the kama. This loss led to the use of a go-toku to support the kama in the furo. Eventually, the enclosed style of the furo gave way to an open bowl with a supporting gotoku. Although air could easily circulate through the space between the kama and the wall of the furo, the himado opening was retained.

Dō-an, 道安, Way-peace, Rikyū’s son, is identified with a style of furo that resembles his father’s mayu-buro, but without the brow of the mayu opening. It could be that a mayu-buro was lifted by holding the brow, as it looks to be a perfect handle, and the brow bridge broke away. Rather than discarding or restoring the furo, the scars might have been smoothed over and finished like the rest of the bowl. Evidently, it was admired, with its new look. However, it came about, the “Dōan buro” was copied countless times in all sorts of material, with as many variations. Nevertheless, the lack of the brow lends a sense of sabi.

The diameter of the inside of the opening of the kiri-kake buro koshiki is 5.5 sun kujira. The diameter of the inner opening of the mouth of Rikyū’s choice of mage mizu-sashi, 水指, bend water-indicate, is 5.5 sun kane-jaku. The openings relate to each other 8 to 10, which may be identified with ya-ta, 八咫, eight-span, as with ya-ta-kagami, 八咫鏡, eight-span-mirror, the Shintō symbol of infinite vastness. Note in the picture the handles of his-haku, 柄杓, handle-ladle, span the openings of the furo and mizusashi. The furo opening is the same as the distance between the fushi, 節, node, and the moon-shape end of the hishaku, and the mizusashi opening is the same as the distance between the fushi and handle end of the hishaku.

To protect the tatami from the heat of the furo, it is placed on a wooden board that is usually lacquered black. The original board was the ji-ita, 地板, earth-board, of the dai-su, 台子, support-of, which has an upper shelf called a ten-ita, 天板, heaven-board, supported on four corner posts, hashira, 柱. The jiita was modified and created for use with the furo and the ro, 炉, sunken hearth. Boards were made smaller for supporting just the furo, and there are several styles of shiki-ita, 敷板, spread-board, that are about one shaku square.

The furo that is known from the time of Rikyū in the 16th century, was a smaller version of large furo and kama that were used in temples. Evidence of this still remains at Sai-dai-ji, 西大寺, West-great-temple, in Nara, where O-cha-mor Shiki, 大茶盛式, Great-tea-mound Rite, is presented. In the ritual, a very large furo and kama and equally large utensils such as the mizusashi, chaki, chasen, and especially large, oversized chawan. Some of the utensils are intentionally huge to delight participants who need held drinking from the enormous bowls. Pertinent, is that the furo and mizusashi are displayed on a very large daisu, that takes up much of a full tatami. These utensils, the furo and kama were part of Buddhist temple presentations of tea. However, the tea bowls are over-large exceptions, and manifest the abundance of Buddhist blessing.

The mask of the kantsuki may have origins in the Hindu deity, Garuda. In Japan, Garuda is called Ka-ru-ra, 迦楼羅, [phonetic sound]-tower-gauze. He is of great size, breathes fire, and eats dragons and serpents, and lives on Mt. Shumisen. There are many features of Karura that may have parallels with the kimen buro.

Karura wears snakes on his wrists, as a belt, a necklace, earrings and in his hair. Snakes are identified with the Naga serpents who guard the Buddha and Buddhism. In a battle with Indra, Garuda lost only one feather, which may be identified with the ha-bōki, 羽箒, feather-brush, the feather used when building the charcoal fire in the Tearoom. Garuda/Karura obtained a vessel of Amrita, elixir of immortality. Although Garuda’s head is bird-like, he has ears, fangs in his beak, and a prominent tongue.

Karura is featured in Shintō dance dramas called Gigaku and Bugaku, and there are ancient mask of Karura that strongly resemble the kantsuki of my kimen buro, with its eagle-like beak, prominent eyeballs, two large fangs. The kan rings of the furo as well as the detachable rings of the kama might suggest the form of snakes. The kama kan have a greater similarity as they are an open coil tapered at both ends, much like a snake. The flaming halo, Karura-en, 迦楼羅焔, Karura-flame, is depicted behind images of Fudō Myō-ō, 不動明王, Un-move Bright-king, who may be represented by the teishu in Chanoyu.

For all Tea presentations, incense is burned in the furo, and the smoke comes out of the himado. In Buddhism, dragons are water creatures that may breathe out clouds that are symbolized by the smoke from incense.

In China, one of the Ryū–sei Kyū–shi, 竜生九子, Dragon-born Nine-child, is= the creature, Xie-chi, 獬豸, which is a kind of lion with one horn on its head. In Japan it is known as kai-chi, 獬豸, and is the Chinese equivalent of the Koma-inu. The Japanese Koma-inu, 狛犬, [Koma is an ancient part of Korea]-dog, is as its name indicates is regarded as a dog. Quite often, pairs of Koma-inu or Kara-jishi are familiar guardians at the entrances to Shintō shrines. The creature with an open mouth ‘ah’ is placed on the right, and that with a closed mouth ‘hum’ on the left, that are aspects of In negative, and Yō positive. Katakana, ア , is drawn on the lid of the kama, to ‘open’ it whether it is open or closed. If the kama is kept closed, an increase heat, Yō, may cause the vessel to explode open, therefore the kama should stay open which is In. It remains In because of its Yō nature. The mizusashi has its lid closed, and stays closed, Yō, because there is no heat to ‘open’ it. It remains Yō because of its In nature.

The Koma-inu is often paired with a Kara–ji-shi, 唐獅子, Tang-lion-of, and placed in front of a shrine for protection. The Kara-jishi with its mouth open is located on the right side of the entrance, and the Koma-inu with its mouth closed is located on the left. The distinctions between the two creatures are often blurred. I have ceramic incense burner which the potter identifies as a Kara-jishi with an open mouth, has a horn on the top of its head, which is usually ascribed to the Koma-inu.

The furo, with the front opening like a mouth, could imply that is making a sound. In Japanese, the sound of a kettle simmering over a fire is likened to matsu-kaze, 松風, pine-wind. The sound is regarded as comforting, primarily indicates that the temperature is right for making tea. However, what uttered sound could be implied by the shape of the himado opening?

Most himado have relatively large openings that are rounded at the bottom with scallop motifs along the top of the hole. These suggest teeth. The opening at the back of the furo is usually smaller and is often a round hole, although some have scallops.

If uttered sounds are implied, could the sounds have their origins in Buddhism, as in the utterance of sutras and other prayers? If the furo is identified with the creatures that are believed to be the nine sons of the Dragon Kings, the sound might be identified with a lion’s roar, which is likened to the voice of the Buddha preaching.

In Buddhism, the Buddha is often called a lion, such as the Lion of the Shaka clan. There are three essential sounds that are uttered before reciting sutras and other religions invocations, and are identified as a mantra. These three sounds are ah om hum, and for Buddhists they encapsulate all sound and are identified with the entire universe.

If these sounds could emanate from the furo, the sound that might be thought to come from the large himado could perhaps be ah. The sound from the smaller opening in the back, and which is often round, could be om, the o in particular. Other minds could rightly disagree with this entire thought. However, if these three sounds may be alluded to with regard to the furo, what of the hum?

The kiri-kake buro has three openings; the front himado, the back opening and maybe disregarded as an opening is the very top itself on which the kettle is placed. It is a closed opening. Could this be identified as representing the sound of hum?

When Buddhist chant, they elongate the vowel sounds for several or more seconds. The sounding is often shifting between ah oh hum. The hum is barely audible. The chant begins with ah shifts to om and back to hum followed by a breath. The mantra is continuously uttered, and with male voices the register is quite low.

If the maegawara is meant to evoke a tongue, it seems appropriate if the openings of the furo are intended to evoke sounds.

When the furo is moved to the opposite side of the Tearoom, it is called gyaku-gatte, 逆勝手, reverse-prevail-hand. In the furo, the trigram for water and north, Kan, locates the furo in the northeast side of the tatami, which would also locate Bi-sha-mon-ten, 毘沙門天, Attend-sand-gate-heaven, in the northeast and the Ki-mon, 鬼門, Demon-gate.

Is there are significance to the character and word mon, 門, gate, in the name of Bishamonten and Kimon? Bishamonten’s other name, Ta-mon-ten, 多聞天, has the word mon in it, but it has a different character, 聞, meaning listen or hear. The character has the mon, gate, radical, and the character for ear, 耳, mimi, as the ear is the gate of hearing.

The kantsuki of the furo and the kama might be likened to the holes in pierced ears, and many Buddhist deities have pierced ears. The Buddha himself, has long stretched earlobes to show that at one earlier time he was rich and had heavy gold earrings. The teishu may be the representative of various beings including Fu-dō Myō-ō, 不動明王, Not-move Bright-god, who has exaggerated pierced earlobes. Perhaps the kama and or furo with its kantsuki might suggest a connection with earlobes and possibly the Buddha or Fudō. The latter is more likely as he is surrounded by fire and flames.

Tea utensils displayed on the take dai-su, 竹台子, bamboo support-of. In the picture, the fu-ro dōgu, 風炉道具, wind-hearth way-tool, are as seen from the perspective of deity in the north.The furo would be on the right, and the mizusashi would be on the left. This is the original placement of the dōgu in ancient times in temples. A kirikake buro with its opening in the back, seen on the right, might suggest the open mouth of the guardian being on the right. The two feet of the furo facing toward deity, is the same as with an incense burner with three feet. There are in truth two shōmen. The principle one is for deity in the north, and a secondary one for humans in the south. Note that the hibashi are leaning toward deity – deity is the true master of fire.

The mizusashi on the left with its closed surface, might suggest the closed mouth of the guardian being on the left. These two aspects would suggest that they are the guardians of something sacred, like a temple or shrine, and that the teishu acts on behalf of the priest.

For further study see also: Furo:Tea and Rice, Furo Ro: Three Forms and Furo and Kama Changes