Go-gatsu

Go-gatsu, 五月, Five-month, bears the old lunar name of Sa-tsuki, 皐月, Swamp-month. This is the time of ta-ue, 田植え, ricefield-plant, transplanting rice into flooded fields, 皐, swamp. The flower called sa-tsuki, 皐月, swamp-month, is the name of a type of azalea (Rhododendron indicum), which blooms at this time.

In 2022, the Tan-go no Se-kku, 端午の節句, Begin-horse ‘s Divide-passage, is held on May 5, which also begins the lunar month of the Snake, Mi, 巳. Tan-Go no Se-kku, is lunar festival, that is held on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, which in 2022 is June 3rd. This date more closely coincides with Bō-shu, 芒種, Grain-beard seed, occurs on June 6th. Bōshu is one of the twenty-four seasonal divisions of the solar year, and begins the lunar month of the Horse, which is the true source of the festival, Tango, Begin-horse. Bō-shu, 芒種, Grain-beard seed, and Tango no Sekku have no real connection, as one event is solar and one event is lunar.

Sho-bu-ro, 初風炉, first-wind-hearth, is the first use of the furo in the Tearoom. The traditional date for the official shoburo is May 10. The Buddhist deity who presides on the tenth day of each month is Nichi-gatsu Tō-myō-butsu, 日月燈明仏, Sun-moon Lamp-light-buddha. He preached the Ho-kke-kyō, 法華經, Law-flower-sutra, the Lotus Sutra, to twenty thousand buddhas. It is said that he had brilliance of the sun, moon, and lamps. It is believed that Tōmyō Butsu is one of the many names of Amida. Although the name of Tōmyō is relatively obscure, Amida’s name is supremely known, and surely has many associations with Chanoyu and the furo. The name, Amida is Amitabha in Sanskrit, which means ‘infinite light’.

Perhaps the date for the shoburo on the tenth of May is that it is approximately the last of the twenty-one days of cha-tsumi, 茶摘, tea-pick. Traditionally, tea is picked on hachi-jū-hachi-ya, 八十八夜, eight-ten-eight-night, after Ri-sshun, 立春, Start-spring. It is impossible to pick all of the tea on one day, so picking begins ten days before, and ends ten days after hachi-jū-hachi-ya. The total number of days is twenty-one, ni-jū-ichi nichi, 二十一日, two-ten-one days, and this is written in the Kanji for the names of many teas, mukashi, 昔, which is composed of twenty, 廾, one, 一, and day, 日, and read mukashi, past times.

Hachi-jū-hachi-ya occurs around the first days of May. This is calculated by the solar calendar. In year 2022, hachi-jū-hachi-ya is on May 2, and May 10 is eight days afterward. Eight is a very symbolic number, so maybe shoburo is eight days after hachi-jū-hachi-ya and chatsumi.

The original fu-ro, 風炉, wind-hearth, was the kiri-kake, 切掛, cut-hang, or kiri–awase, 切合, cut-gather, which has a kama, 釜, kettle, resting on top of a upright collar of the furo. A later development was the open bowl furo, such as the mayu bu-ro, 眉風炉, eyebrow wind-hearth, which required the use of a trivet, go-toku, 五徳, five-virtues, to support the kama, 釜, kettle. Tradition places the metal furo on a mirror-finish black lacquered wooden board, shiki-ita, 敷板, spread-board, and a ceramic furo on a black lacquered wooden board with graduated grooves, ara-me ita, 荒目板, rough-eye board.

Because it has no handle, a kama has lugs called kan-tsuki, 鐶付, metal ring-attach. The lugs are often in the form of head of an oni, 鬼, demon, which may actually be a dragon head, ryū-zu or tatsu-gashira, 竜頭, dragon-head. This is especially true with the ki-men bu-ro, 鬼面風炉, demon-face wind-hearth, which has demon/dragon head kantsuki with a loose ring held in the mouth. In Asian belief, dragons bring rain, and are closely connected with water, so that their images on the kama and furo act as protectors against fire. Further evidence is found with Rikyū’s un-ryū gama, 雲龍釜, cloud-dragon kettle, with its imagery of a dragon, clouds, and rain.

In the Western Han Dynasty, dragons were all three-clawed, and in the Song Dynasty, they became four-clawed dragons. With the passage of time, people combined the two when drawing dragons. The front two feet of the dragon have three claws and four claws on the hind legs. In the Yuan Dynasty, five-clawed dragons began to appear, but they were only reserved for the royal family. When people painted pictures of dragons, they were still three-clawed dragons or four-clawed dragons.

In China, doubled numbers such as three and three were considered unlucky, and had special ceremonies to appease the troubling spirits. The number five doubled was especially dangerous, and the dragons that lived in the rivers had to be appeased with offerings. So, the dragon boat festival was created to held on the fifth day of the fifth month. Japan adopted many cultural aspects from China, and some of the rites lost their dangerous protective natures to celebrations. The lunar events change when they are observed, because of the variable nature of the moon. Tradition wins over factual reality. In some places in Japan on May 5th, to celebrate Tango no Sekku, they have boat races, ryū-shū kyō-sō, 龍舟競漕, dragon-boat compete-rowing. Perhaps there is some connection between the dragon boat and the dragon head on the kama and furo, and their initial presence on Tango no Sekku. There is water in the kama.

There is also the consideration of the use of a gotoku. In the previous months of March and April the kama in the ro did not require the use of a gotoku to support the kama. These were the tsuri-gama, 釣釜, suspend-kettle, and suki-gi gama, 透木釜, through-wood kettle. The same is true of the kiri-kake buro, which does not have a gotoku to support the kama. Where a gotoku is not used to support the kama, Rikyū advised the use of a futa-oki, 蓋置, lid-place, in the form a gotoku to rest the lid of the kama.

Iris flowers are in bloom at this time of the year, and the most iconic is the shō-bu, 菖蒲, iris-bulrush. The two Kanji together are also read ayame, which is a blue-purple iris known and beloved in Japan, and everywhere the iris can grow.

A kind of iris that is a favorite in Japan is the kakitsubata, 杜若, grove-young, rabbit ear iris (Iris laevigata). One of Kyoto’s most famous sites for kakitsubata is the iris pond at Ō-ta Jin-ja, 大田神社, Great-ricefield God-shrine. I have made Tea at this shrine several times; a Setsubun offering, and a cha-bako presentation very near the place across the pond. The word kakitsubata is derived from kakitsuke hata, 掻きつけ 機, rub loom, which is an ancient dyeing technique of rubbing flowers, such as the iris and bush clover, onto fabric that was usually hemp.

To make a bamboo futaoki, the bamboo is cut with the root end up so that the lidrest is ‘upside down.’ A hole is cut in the septum making it impossible to hold water, which changes the bamboo from being a container, In, to a support, Yō. The lowest level of the bamboo fushi / node determines the shōmen. The height of Rikyū’s futaoki is 1.8 sun kane-jaku. The measurement between the bottom of the futaoki to the lowest level of the fushi is 8/10th the height of the futaoki. The numbers 8 and 10 are manifestations of ya-ta, 八咫, eight-span, which in Shintō, is found in the Ya-ta Kagami, 八咫鏡, Eight-span Mirror, the sacred symbol of Amaterasu, the sun goddess.

In ken-dō, 剣道, sword-way, various pieces of equipment are wrapped in cloth that has a pattern called ayame kazari, あやめ飾り, iris display. The word shōbu for the iris, is wordplay on shō-bu, 勝負, win-defeat, so that the iris with its long slender blade-like leaves, is emblematic of masculinity, and is displayed on Boy’s Day, Tan-go no Hi, 端午の日, Begin-horse, The original meaning of the Kanji, 午, began with the concept of ‘meeting head on.’

The day of May 5, 2022, is marked with the zodiac sign of Tsuchinoe Uma, 戊午, Earth’s older brother Horse. Ko-domo no Hi, 子供の日, Children’s Day. Ri-kka, 立夏, Start-summer, begins the Mi-no-tsuki, 巳の月, Snake’s Month. Tan-Go, 端午, Begin-Horse, beginning of the month of the Horse: one of the ancient five annual festivals: Go-se-kku, 五節句, Five-season-passage. Originally, tan-go, referred to the emperor’s bullrush-gathering, for the bath. The true and original shō-bu, 菖蒲, iris-bulrush, is the Acorus calamus, which has been a powerful medicine and drug for centuries in Asia. It does not have the familiar iris flower, but a bulrush with a stalk-like flowered stem.

Bundles of shōbu leaves together with sprigs of yomogi, 蓬, mugwort, are put into the bath for healthful benefits; shō-bu-yu, 菖蒲湯, iris-bulrush-hot water. Such bundles are also put on the eaves and roofs above entrances for preventing illness from entering.

Seki-shō, 石菖, stone-rush, Japanese sweet flag (Acorus gramineus), is displayed in the tokonoma for a night-time Tea gathering called yo-banashi, 夜咄, night-conversation. The roots of the whole plant are nestled into a large piece of sumi, 炭, charcoal, in a water-filled bowl placed on a round, black-lacquered usu-ita, 薄板, thin-board, maru-kō-dai, 丸香台, round-incense-support. It is believed that the plant helps to purify the air. The sekishō is a living, water, In counterpart to kō-ro, 香炉, incense-hearth, that is dry, fire, Yō.

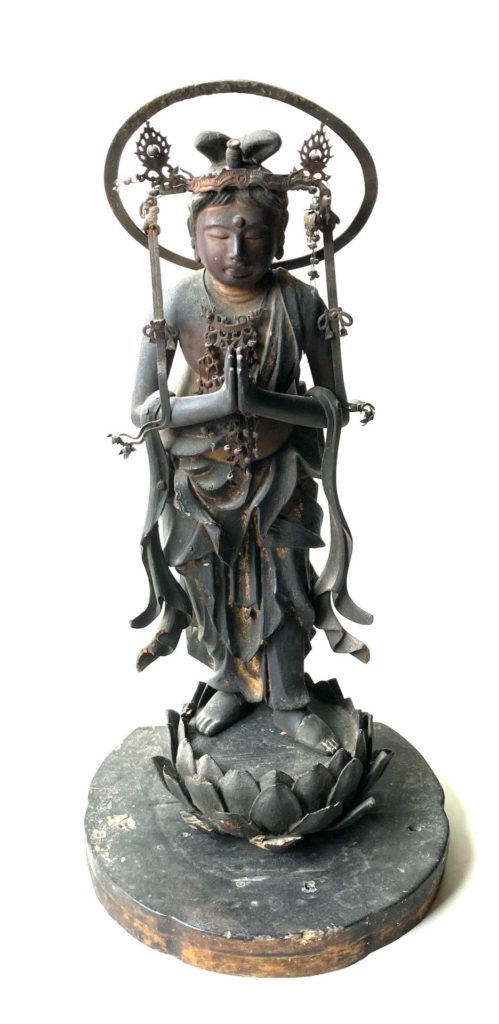

The Buddhist guardian of the fifth month is Sei-shi Bo-satsu, 勢至菩薩, Strength-attain Sacred tree-buddha, is more formally named Dai-sei-shi, 大勢至, Great-strength-attain. Together with Kan-non Bo-satsu, 観音菩薩, See-sound Sacred tree-buddha, they accompany A-mi-da Nyo-rai, 阿弥陀如来, Praise-increase-steep Like-become, the Buddha of Compassion.

The incense smoke-darkened gilt wooden figure of Sei-shi Bo-satsu, 勢至菩薩, Strength-attain Sacred tree-buddha, dates from the Muro-machi Ji-dai, 室町時代, House-town Time-generation, 15th century. Seishi is depicted holding his hands together in a ‘prayer’ manner. An emblem of Seishi, located just above his forehead, is a sui-byō, 水瓶, water-bottle, containing sacred kan-ro, 甘露, sweet-dew. The ornamental headdress with long, pendant streamers and necklace are later additions. Additional central parts of the crown are lost. During the Tokugawa rule, every Japanese person had to be a Buddhist, and at that time, I believe that there was a countrywide movement to adorn Buddhist imagery with almost identical metal and bead ornamentation. So prevalent was this adornment, that later artists included the iconography on new figural votive images.

A more complete crown is located on the figural image of a companion figure of Kannon, pictured above, which contains tiny disks of the sun and moon, ‘phoenixes’, Go-rin-tō, 五輪塔, Five-ring-tower, etc. An original miniscule figure of Amida was located above the forehead, but has been lost, only a tiny metal wire is evidence of its former presence. I believe that the metal ring halos on both figures are original. The crowns and necklaces could be relatively easy to remove, however, they are integral parts of their histories. It is written that the crown of Seishi has five hundred jewel flowers, and each flower has five hundred treasure supports.

Seishi is located in the south, and is identified with the element of Fire, whereas Kannon in the north is identified with the element of Water. The lotus is the emblem of Kannon. It is interesting to note that Seishi carries on his head a bottle of sacred water. Seishi may also be identified with the last of four guests of a Tea gathering in a yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, but does not sit directly on the place of Seishi. The last guest may help and assist the teishu, and even enter the mizu-ya, 水屋, water-room. The last guest is called tsume, 詰, which also means tea master. Seishi may be identified as the last guest. There may be wordplay on tsume, 爪, talon, of the gotoku.

There is a remote possibility that the mizuya is also the realm of Seishi, as there is the essential water vessel, suibyō of Seishi, but is called a mizu-game, 水瓶, by another reading. Kannon in the north and part of the tokonoma, makes it a kind of worship room. The Tea utensils on the ten-mae-za, 点前座, offer-fore-seat, are located in the northwest corner of the Tearoom which is identified with Amida Nyorai, and so identified with the ten-mae, 点前, offer-fore. The area of the Tea utensils is rather like an altar dedicated to Amida. This is especially true when the utensils are displayed on the formal Tea stand, dai-su, 台子, support-of. With these possible arrangements, the Tearoom with the mizuya may be identified as altars for the Raigō of Amida. One of Rikyū’s favorite kettles is the A-mi-da-dō gama, 阿弥陀堂釜, Amida-hall kettle.

It has been said that the suki-gi gama, 透木釜, through-wood kettle, used in April is to cover over the fire in the ro is to lessen the heat escaping into the Tearoom. This does not quite hold true, as Omotesenke uses the tsuri-gama, 釣釜, suspend-kettle, in April, which often reveals more of the fire in the ro. Allowing the concept of covering the fire in the ro is valid, is it possible that the first furo of the season would be rather more closed than open. A closed furo would be the kiri-awase, 切合, cut-together, or the kiri-kake, 切掛, cut-hang, where the kama rests on the color of the furo. An open furo would be like the mayu-bu-ro, 眉風炉, eyebrow wind-hearth, or the Dō-an bu-ro, 道安風炉, Way-peace wind-hearth, which are open bowls with a gotoku to support the kama.

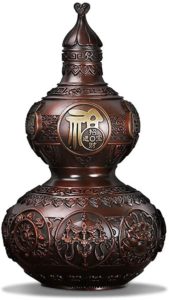

The essential form of the kiri-awase furo resembles a bottle gourd, hyō-tan, 瓢箪, gourd-basket, which is sacred to Taoism. Also, the image of Amida seated on a lotus does, in my mind, resemble a kiri-awase furo. The A-mi-da Rai-gō, 阿弥陀来迎, Praise-increase-steep Come-become, is depicted in countless hanging scrolls, and although not often displayed in the tokonoma for a Tea gathering, it plays an important role in the life of the Japanese.

The furo may be used throughout the entire year. When a ro is present, it is opened and used from early November through the end of April of the following year. This is the custom in Kyōto, which is in a temperate zone of the northern hemisphere of the earth. Followers of a particular Chanoyu tradition and school adhere to those procedures. This can pose a concern. The ro is used when it is cold to provide additional heat to the Tearoom. In a modern world, there is heat and cold available at the press of a button, so that there is no real need for special heat or cooling. In modern Japan, many Tearooms are located in air-conditioned buildings, which is especially desired in very hot summers in Kyōto and elsewhere in the country. Nonetheless, furo in summer and ro in winter.

In pre-modern times, regardless of the season or weather, the temperature inside was the same as outside. There weren’t refrigerated or heated buildings. Therefore, in Kyōto, the traditional ‘home’ of Chanoyu, it was only natural to use the furo in summer and the ro in winter. People became used to the current climate conditions. There is a Japanese expression: ga-man, 我慢, self-slow, which means to endure any adversity. Well, almost anything. ‘Slowing’ one’s ego is an aspect of Zen Buddhism.

Tradition has the opening of the ro on the first day of the Wild Boar in the 10th month. But this varies from year to year. Sen no Rikyū was asked when to open the ro. He responded, when the yuzu turns yellow. The yuzu, 柚, citron, (Citrus ichangensis x C. reticulata), which meant when it was cold enough. Again, it is rather subjective. There seems to be no such question put to Rikyū with regard as to when to begin using the furo.

In the traditional mizu-ya, 水屋, water-room, where preparations are made for a Tea gathering, there is a heat source to heat water. There is always a need for hot water independent of that in the Tearoom. Heat is provided by a charcoal fire in a furo, or a gan-ro, 丸炉, round-hearth, that is set in the floor. A much-appreciated source of heat in winter, a possible scourge in summer. In former times, and at present as well, tea was prepared in the mizuya and brought out to guests assembled in the Tearoom. This was the mode of Tea presentations in the 15th century in Ginkakuji’s Tōgudō room named Dōjinsai. Tea was prepared in the adjoining room, and served to guest in the yojōhan, where there was no heat source for hot water. In essence, the manner of preparing Tea in the adjoining room, became the ‘real’ Tea ceremony place, where the maker of the tea became identified as teishu, and the assistants became the kyaku. The ‘guests’ gathered in the ‘tearoom’ became incidental. The room Dōjinsai was created by Ashikaga Yoshimasa to study and practice Pure Land Buddhism. Drinking Tea was a part of his practice. Later, the Dōjinsai became identified as a ‘Tearoom’. The main room of the Tōgudō is the Butsu-ma, 仏間, Buddha-room, which is for the worship of Amida Nyorai.

Koi nobori, 鯉幟, carp streamer; fabric or paper windsock that is modelled on the carp is raised for Tango no Sekku. There is a tradition in Japan when a large black carp streamer is raised at the birth of the first son. The koi is an emblem of victory over adversity, as the fish swims up a taki, 滝, waterfall to spawn. The word nobori also means nobori, 上り, to ascend.

The carp ascending a waterfall is likened to the development of the kundalini, the maturation of the nervous system. The waterfall is likened to the spine, and the fish represents the determination of attaining a goal, the upper pool of water, tan, 潭, deep water pool, which is likened to the brain, where the fish is transformed into a dragon, the emblem of Buddhist enlightenment, satori, 悟り. As another child is born, a smaller koi streamer of a different color is added. A myriad of hanging scrolls bearing an image of a carp swimming up a waterfall have been created for the millions of Japanese to hang in their tokonoma for Tango no Sekku. Also, the waterfall is to give a cooling effect in the increasing heat of summer.

An essential sweet for Tango no Sekku is kashiwa-mochi, 柏餅, oak-sweet rice, which is sweetened, soft mochi filled with azuki an, 小豆餡, red bean-jam, and wrapped in a kashiwa no ha, 柏の葉, oak ’s leaf. Created in the 17th century, and so much loved, that it has a wide range of fabrications. The mochi has a prime addition of shiro mi-so, 白味噌, white miso, that is familiar in the Kyōto area, but almost unknown in other parts of Japan. The leaf has a bit of controversy, and there are several contested varieties. Some leaves are green, some aged but still pliant. Some leaves have smooth backs, while others are fuzzy.

The standard kashiwa mochi filled with red bean an has the underside of the leaf on the outside, while the sweet with the miso filling has the upper surface of the leaf on the outside. The leaf is not eaten, as one does with other types such as the preserved cherry leaf on sakura-mochi. The oak leaf, rife with symbolism as it stays on the tree, until new buds push the old leaves off. Continuation of lineage. The leaf imparts a flavor and taste to the mochi.

For further study, see also: Tea in May, April in Japan: Following Elephants, May: Still Following Elephants