Kagami Mochi

Things that may be displayed on the sanbō for the New Year, include a sen-su, 扇子, fan-of, kon-bu, 昆布, descendants-cloth, kelp, a stick with hoshi-gaki, 干柿, dried-persimmon, ura-jiro, 裏白, underside-white, a primal, un-changed fern, Gleichenia japonica, shi-hō beni, 四方紅, four-direction red, square of white paper with red edge, laid diamond-like on the sanbō to create 8 ‘directions’, and red and white cut paper shi-de, 四手, four-hand, embodying In, 陰, negative, red, and Yō, 陽, positive, white.

San-bō, 三宝, Three-treasures, the Three Jewels, the Triple Gem; Triratna the Three Treasures of Buddhism: Buddha, Dharma (Law), Sangha (Community). In Shintō, san-bō refers to products of the sea foods, mountain plants, and field rice. Typical Shintō offerings are rice, salt, and water. The stand is also called a san-pō, san-bō 三方, Three-directions. The tray and the supporting base may have mitered corners, so that is has 8 sides, and 8 is symbolic of Infinity in Space, omnipresence.

The foods that are displayed on the sanbō are not exactly ‘offerings’ to the kami, 神, deity, because offerings are the property of the deity. Foods that are placed before deity are intended to be blessed by the deity, and then eaten by humans. The foods displayed on the sanbō are designated in the phrase, Kami ni shuku-fuku sareru tabe-mono, 神に祝福される食べ物, deity to celebration-fortune do eat things.

The orange-colored fruit on the top of the mochi is the daidai, 橙, bitter orange, Citrus aurantium. The name daidai is wordplay on 代々, meaning generation-generation, which is auspicious for the New Year. One or more leaves should be attached, which refers to the nature of the fruit which does not fall off the tree even when it is ripe, and therefore is again auspicious; endurance. The small, evergreen tree has many large thorns, toge, 棘, which are symbolic of protection. The peel has been used in Chinese medicine for centuries, and is used in making marmalade.

The mochi after it is displayed and broken is cooked and put into a traditional soup called O-zō-ni, お雑煮, hon.-miscellany-boil. Ozōni is a clear soup made with kon-bu, 昆布, descendant-cloth, (kagami mochi offering), katsuo-bushi, mochi, nin-jin, 人参, person-shrine visit, kama-boko, 蒲鉾, rush-halberd, fish curd, green leaf, mitsu-ba, 三つ葉, three-leaves, Cryptotaenia japonica, yuzu kawa, 柚子皮, Citrus-of peel, (may have originally been daidai). Recipe and ingredients vary. Kagami mochi ingredients for ozōni.

The bitter orange flowers bloom in spring, and are large, white, about 4 cm in diameter, and the upper end is half-opened and inverted. It is curious to note that the Kanji for thorn, 棘, is composed of two joined Kanji, 朿, thorn. Another Kanji that is composed of two thorn Kanji, 朿, one on top of the other is natsume, 棗, jujube, a tree that has many thorns. The fruit of the natsume is the model for the much admired cha-ki, 茶器, tea-container.

Mizu-hiki, 水引, water-draw, is a paper string tied in a bow, musubi, 結, on a gift or offering. The string is usually half red and half white, and may be a single string or several strings bundled together. The mizuhiki is ‘tied’ in a myriad of styles and colors, and shaped into small to large objects of felicitation. In many kagami mochi displays a mizuhiki bow is tied around and between two pieces of mochi. Perhaps the mizuhiki between the two pieces of mochi was to symbolically represent the sun or the moon and its reflection in the ‘water’ of the mizuhiki.

The following has only recently come to light, as the origin of the word mizuhiki has been a question for a very long time. Mizu-hiki originated in China, and during early Heian period, the threads of the ‘mizu-hiki’, 水引, were made of asa, 麻, hemp. The hemp stalks were processed by soaking in water for about ten days to loosen the fibers. This may be the origin of ‘water-drawn’. Mizuhiki has been the name since the Heian period, but before that, it was called kurenai, くれない, 紅, red. After the Muromachi period, the hemp cord was replaced with twisted paper, that has continued to this day.

Another object that may be included in the kagami mochi is a Japanese spiny lobster, I-se e-bi, 伊勢蝦/伊勢海老, That-force Sea-elder, Panulirus japonicus. Ise Jingū is the great shrine dedicated to Amaterasu. The living crustacean is regarded as being white, and turns red after cooking, which is itself a manifestation of the auspicious term of kō-haku, 紅白, red-white. As a creature of the ocean, the lobster, together with the konbu emphasizes the aspect of the sea of the kagami mochi.

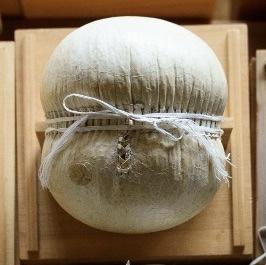

It may have been that original intention to make a single sphere of mochi, and tie mizuhiki strings around the middle, like an obi. Perhaps the original intention was to form mochi into a sphere, but the softness and weight of the mochi sphere causes it to collapse into an oval.

Dan-go, 団子, round-of, small ball of mochi are made to be spherical. It may be that the word ‘mochi’ means to be handled to be kneaded 持, mochi. The Kanji for mochi, 餅, rice cake, is composed of shoku, 食, food, and awaseru, put together. This may be related to the word ‘mochi’, 持, having, which is composed of te, 手, hand, and tera, 寺, temple, and implies ‘handing to deity’. Mochi is kneaded with both hands, and then offered to deity.

The mochi rice is manipulated, handled, kneaded, turned, made round smooth with a matte finish, and is created in part with kata-kuri-ko, 片栗粉, direction-chestnut-flour. Katakuriko is made from the root of the dogtooth violet, but is difficult to find, and so potato starch is substituted. Kagami mochi sags, and through its weight gravity causes the ball to become flattened somewhat. The intention is to make the mochi into spheres. The difference in the sizes of the mochi is an aesthetic choice, and to make the two pieces resemble a hyō-tan, 瓢箪, gourd-basket.

Dried, natural hyō-tan, 瓢箪, gourd-basket, with red cord to secure the stopper. The bottle gourd is sacred to Taoism, and in Buddhism is symbolic of gen-gen, 玄々, mystery-mystery, compounded unknowable.

Gen-bu, 玄武, Black-warrior, is the Buddhist guardian of the north. As a celestial creature of the north quadrant of the heavens is a hybrid turtle and snake. Bi-sha-mon-ten, 毘沙門天, Help-sand-gate-heaven (deva), takes the place of Genbu.

Displays of kagami mochi are placed in various places around the home other than the tokonoma, at businesses, any location where blessings may be wished. Such places include a Kami–dana, 神棚, God-shelf, Butsu-dan, 仏壇, Buddhist-altar, where there is fire as in the kitchen, a potter’s studio, etc. and a water source as a well, the furo bath, etc.

Kagami mochi is primarily composed of three parts: two settled spheres of mochi with a daidai placed on top. The standard snowman is composed of three round parts of snow of varied sizes. There are several aspects of the mochi that have some, if only vague, association with the snowman. White. Orange color citrus – carrot nose. Folding fan – top hat. Mizuhiki tie and bow – scarf. In Chanoyu, sumi, 炭, charcoal – coal eyes. Some kagami mochi have a stick with kushi-kaki, 串柿, skewer-(dried) persimmons, stick arms.

Kushi 串 refers to the line or stick that passes through to skewer objects such as food. The Kanji 串 has different size squares on the ‘skewer’, just as the round kagami mochi pieces are of different sizes.

At Urasenke, and places where Chanoyu is important, pieces of charcoal are displayed on a sanbō. Sumi provides the life of the fire to heat water for Tea. Custom chooses a wa-dō for the ro fire, as the main element of the display. Adornments vary greatly. In the above photograph, the sheet of paper is one of the kami kama-shiki, 紙釜敷, paper kettle-spread. Although the number of sheets of paper varies, the pack of papers may be identified with a Buddhist sutra. The type of paper used for the kami kamashiki is called dan-shi, 壇紙, altar-paper.

The term kagami mochi was used in the Heian period, and is mentioned in the Tale of Genji. It is believed that the present appearance of kagami mochi occurred in the Muromachi period. Ancient Japanese mirrors, originated in China, were round, flat bronze mirrors that had one solid, flat ‘mirror’ side, that needed frequent polishing. The obverse had raised decoration, and a small lug-like handle for a cord. A mochi ‘mirror’ is round, but is more like a settled sphere, and that may give more of a reference to the moon. The sun is Ama-terasu, 天照, Heaven-brightener, and the moon, a reflection of the sun is identified with her brother Tsuki-yomi, 月読, Moon-read. The sun and the moon are spheres, and were born from the eyes of Izanagi, when he bathed after seeking his wife in the underworld. It is thought that the daidai represents the red maga-tama, 勾玉, curved-jewel, and the persimmon skewer represents the sacred imperial sword.

For a New Year Tea, a kakejiku with an image of the rising sun, Hi no de, 日の出, may be displayed in the tokonoma. The Tearoom is oriented with the tokonoma in the north. Displaying a scroll of the rising sun would ‘change’ the location of the back wall of the tokonoma to the east, the sun rises in the east. The New Year theoretically is the beginning of spring.

Hishi-mochi, 菱餅, rhombus-mochi sweetened pink, flavored with gardenia seeds, white flavored with water chestnut, and green mochi flavored with mugwort, which is served on Hina-matsuri, 雛まつり, Chick-festival, which represents the imperial court. The diamond-shape appears in the Asuka period, exclusively for the imperial court, and is symbolic of Yō, Yang, power in all directions.

Hishi-hanabira-mochi, 菱葩餅, diamond-flower petal-mochi, is a Japanese sweet, wa-ga-shi, 和菓子, harmony-sweet-of, that is usually eaten at the beginning of the year. Hanabira-mochi is also served at Hatsu-gama, 初釜, First-kettle, the first tea ceremony of the New Year. The sweet is made of a disk of white mochi with a pink an lozenge shape, filled with white miso an, nin-jin / red carrot, and go-bō, 牛蒡, ox-burdock, the latter roots are candied over a long period of time. The disk is folded in half with the ninjin and gobō sticking out at both ends. One must learn how to eat this treasured sweet – carefully, as the almost-liquid miso oozes out so easily.

The tokonoma may also have a willow branch displayed for the New Year. Ideally, the musubi yanagi, 結柳, tied willow, is a long-trailing branch held in a bamboo container hung on a hook in the back left corner post of the tokonoma. With the ‘change’ in direction, the post may be identified with the northeast and Risshun, 立春, Start-spring. The budding willow heralds the arrival of spring.

The musubi yanagi has a branch tied in a loop around the other branches. I have learned many things about the meaning of the loop and its significance. There may be other symbolism. The loop or circle may suggest the ensō, 円相, circle-phase, of Buddhism, meaning nothing and everything. This is shown in Picture 8 of the Jūgyūzu, 十牛図, Ten-ox-pictures. The circle may represent a mirror, which is the symbol of the sun and Amaterasu. Kannon Bosatsu is also identified with the willow and the mirror.

When having an image of the rising sun in the tokonoma, perhaps the circle of the willow represents the moon; tsuitachi, 朔, first day of month. The new moon of the first month. This Kanji, 朔, is also identified with the north direction. The willow circle is vacant, only suggesting the concept of the moon that cannot be seen when it is new. The sun is Tai-yō, 太陽, Great-Yang, and the moon is Tai-In, 太陰, Great-Yin. However, a picture is a visual representation of the sun and is therefore In. The willow circle alludes to the moon, and is therefore Yō.

The willow branch is symbolic of the Ama-no-gawa, 天の川, Heaven-’s-river, that is visible at night, but invisible during the day, so that it is Yō. The willow ‘river’ is a physical thing, so that it is In. One may be reminded of the Kanji for Rikyū’s name Eki, 易, Change, which combines sun and moon.

Yugyō means to wander aimlessly, and often refers to Buddhist pilgrimage. An interesting aspect of the production is the pattern of the actor’s coat, which is composed of willow branches and curious balls. The balls are from an ancient Heian court game called ke-mari, 蹴鞠, kick-ball, that is similar to hacky sack and soccer, except that the ball must kept in the air, and the player is not allowed to touch the ball with the hands. The square playing field has different trees at the corners; cherry – northeast, pine – northwest, willow – southeast, and maple – southwest.

The kemari ball has an atypical doubled form. It is made two pieces of deerskin, and stitched together with the leather from the back of a horse, and inflated, with a standard diameter of around 6.6 sun kane-jaku, and painted white. The form of the ball, to some people, may seem a little like the two pieces of kagami mochi.

Large suzu, 鈴, bell, shin-chū, 真鍮, true-brass, full H. 5 sun kane-jaku. At the bottom of the bell is a long slit, with a round or ‘heart’ -shaped hole at each end of the slit. The escutcheon is in the form of a kiku, 菊の花, chrysanthemum’s flower; kiku is wordplay on 聞く, listen. The chrysanthemum is emblematic of the emperor and omnipresence.

The objects of the New Year festivities display are for individual senses. Everything is for sight – eye; the mochi is for taste – tongue; the kick ball is for touch – foot; the bell is for hearing – ear; the fragrant daidai citrus fruit is for smell – nose.

Another citrus fruit that is displayed for the New Year is the Bu-sshu-kan, 仏手柑, Buddha-hand-citron. The multiple ‘fingers’ are symbolic of the Buddha’s hand that nothing will escape his grasp. Rikyū said that the ro should be opened when the yuzu, 柚, citron, turned yellow, Citrus ichangensis x C. reticulata. It was the custom to open the ro on the first day of the I, 亥, (zodiac) wild boar, of the tenth lunar month, which is marked with the same sign of the Wild Boar. However, that day occurs with great irregularity, and varies by nearly thirty days.

Adornments and offerings for Shō-gatsu kazari, 正月飾り, Correct-month display, include a nioi bukuro, 匂い袋, fragrance bag. Ka-ri-roku, 訶梨勒, scold-pear-rein, Schizonepetae Herba, is the major ingredient of medicinal herbs, woods, spices, etc. in a sachet, nioi-bukuro, 匂い袋, fragrance-bag, displayed especially at the New Year. The mixture is widely varied with herbs such as cloves, cinnamon bark, and aloeswood with the fruit of the mulberry, which is said to have the power to cure various ailments. Since the Muromachi period, it has been used as a tokonoma decoration to ward off evil spirits. It is said that if you hang the fragrance bag at your front door for the New Year, you will ward off evil spirits for the whole year. The fruit of the kariroku is likened to a pear-shape, which could be extended to gourds.

Objects that are composed of two orbs may have their origins in the hyō-tan, 瓢箪, gourd-basket, the bottle gourd that is sacred to Taoism and symbolic in Buddhism. The essential hyōtan has orbs of different sizes with the larger as a base, the smaller on the top.

Kagami-biraki, 鏡開き, mirror-open; breaking open, with a hammer, the mochi that hardened like stone. The mochi should not be cut with a knife, as it means to sever relationships. Kagami-biraki is held on January 11th. Until the early Edo period, it was held on the 20th day of the lunar 1st month, however, Tokugawa Ieyasu died on 20th day of lunar 4th month in 1651, so the date for kagami-biraki was changed to the 11th day. The 20th day of every month is the en-nichi, 縁日, feast day, of Jū-ichi-men Kan-non Bo-satsu, 十一面観音菩薩, Ten-one-face-see-sound Grass-buddha.

Part of the kagami mochi display may include a large piece of kon-bu, 昆布, descendant-cloth, kelp, laminaria. Konbu is a prime ingredient of soup stock, kon-bu-dashi, 昆布出し, kelp-out. The word konbu is also pronounced kobu, and there is wordplay on yorokobu, 喜ぶ, joyful. Ishi-uchi Kobu Kannon, 石打こぶ観音, Stone-hammer kobu See-sound. The meaning of ‘kobu’ seems vague as it is written in Kana. Homonyms are, 子生, Rat-born, Kannon is the protector of the Ne-doshi, 子年, Rat Year; 子宝, Rat/Child-treasure; kobu, 瘤, swelling.

Konbu grows in the sea, and has been used in making dashi for soup and for cooking other foods. The sheet of konbu displayed on the kagami mochi on the sanbō represents the sea its salt is one of the three Shintō offerings. Some kagami mochi displays the konbu between the two pieces of mochi, which may suggest the sun or the moon with its reflection on the water. This is the mirror of ‘mirror’ mochi. In lieu of the konbu

There is a hot beverage, ko-bu-cha, 昆布茶, kelp-tea, made of dried kelp that is popular around the world. One of the brands of kobucha is named Kannon Kobu, that is available near temples dedicated to Kannon. Originated near a Kannon temple on Chiku-bu-shima, 竹生島, Bamboo-live-island, in Lake Biwa. The image of Kannon is imprinted on the square of konbu. It is curious that the Kannon temple is identified with ‘stone hammer’, which is used to break the New Year’s mochi that is hard as stone.

The origin of the name Japan, Ni-ppon, and Ni-hon, 日本, sun-origin, is from China’s perspective, the land where the sun rises in the east. A kakemono with a image of the rising sun displayed in the tokonoma, identifies the back wall as being in the east. The kagami mochi displayed before the image of the sunrise, is a physical manifestation of the sunrise. Perhaps the daidai represents the sun, and the two pieces of mochi are reflections of the sun. In the photograph above, reflections of the sun in the water appear larger nearer the observer. The konbu, growing in the sea, represents the sea. The orange-color daidai of the kagami mochi is above the konbu and mochi, that may be likened to the reflections of the sun on the waves of water.

After the mochi has been broken open with a hammer, kagami biraki, the daidai may be put into the fu-ro, 風呂, wind-spine, bath. Or it may be cut in half to squeeze out the juice mixed with hot water to drink. When discarded, the daidai should have salt sprinkled on it, and be wrapped in paper with a grateful spirit.

According to custom, the konbu and the umeboshi are put into tea, which called Ōbukucha. In Chanoyu, the konbu and umeboshi are eaten separately before drink the Ōbukucha which is matcha not sencha. The konbu, tied in a knot, musubi, and koume/umeboshi are served to guests on a sanbō, and each guest takes one of each.

Musubi kon-bu, 結び昆布, tied descendant-cloth, are small pieces of kelp, salted, tied in a knot, and dried. Ko–ume, 小梅, small-prunus, are similar to ume-boshi, 梅干, prunus-dried, except that the ume are small, less salty, and have a crunchy texture. Ka-chi-guri, 搗栗, pound-chestnut, and ka-chi–guri, 勝栗, victory-chestnut. These foods are intentionally hard and challenging to eat so that eating them will strengthen the security of the teeth, and the jaw muscles. These dried nuts are eaten before battle, Shō-gatsu, 正月, Correct-month, eat or drink Ō-buku-cha, 大福茶, Great-fortune-tea, sen-cha, 煎茶, steep-tea, on the third morning of New Year, recite the Nenbutsu.

Ōbukucha was first drunk at Roku-ha-ra-mitsu-ji, 六波羅蜜寺, Six-wave-spread-secret-temple, Buddhist temple in Kyōto, in 951 introduced by emperor Mura-kami, 村上, Town-above, to help ward off an epidemic ravaging the capital. Roku hara refers to the six realms of Buddhist existence from hell to heaven, with six different manifestations of Jizō in each of the six realms. Hence the importance of reciting the Nenbutsu, “Na-mu A-mi-da-butsu”, 南無阿弥陀仏, South-not Praise-increase-steep-buddha.

Ōbukucha is primarily sen-cha, 煎茶, steep-(leaf)tea, made with tea leaves shaped like yanagi–ha, 柳葉, willow-leaf, musubi konbu and kō-ume, 小梅, small-prunus. At Urasenke in Kyōto, Ō-buku-cha is made with ma-tcha, 抹茶, powder-tea. The musubi konbu and the ume are eaten separate from the tea.

Jo-ya gama, 除夜釜, end-night kettle, is the last Tea of the year presented in the Ryū-sei-ken, 溜精軒, Gather-spirit-eave. The wall at the end of the dō-gu, 道具, way-tool, tatami, has a lattice made of old handles of hi-shaku, 柄杓, handle-ladle. This six-tatami room is the main hallway of Konnichian, that is used as a Tearoom only on New Year’s Eve. The ro is gyaku-gatte daime-giri. After the Tea is concluded, a large amount of charcoal is added to the ro, which is then covered over with a ceramic cover in the form of a Kara-ji-shi, 唐獅子, Tang-lion-of. On the morning of the 1st day, at the hour of the Tiger, the charcoal fire is moved from the ro in Ryūseiken to the ro in the Rikyū-dō, the On-so-dō, 御祖堂, Hon.-ancestor-hall, which is a shrine and Buddhist temple of the Urasenke family, and a Tearoom named Sei-jaku-in, 清寂院, Pure-tranquility-(memorial temple).

On New Year’s Day, at the hour of the Tiger, Tora no koku, 寅の刻, Tiger ’s time (the time between 3-5 am, around 4 am), the charcoal fire is moved from the ro in Ryūseiken, the ro in the Rikyū-dō. The family assembles, and Iemoto prepares Ōbukucha, which is first offered to Rikyū’s spirit, and then shared by the family.