Tea and Moon Viewing

Ku-gatsu, 九月, Nine-moon, is the time for the Japanese to enjoy looking at the full moon, tsuki-mi, 月見, moon-see, in September.

The Kanji for the living rabbit is usagi, 兎, which means both rabbit and hare, whereas the Kanji for the Asian zodiac sign of the hare or rabbit is u, 卯. Susuki, 芒, eulalia, pampas grass flowers open and become fuzzy, and are held up to gaze at the moon through the grass. This effect may be called oboro-zuki, 朧月, hazy-moon, especially on a spring night. The Kanji, 朧, is composed of the Kanji niku, 肉, for flesh, or tsuki, 月, for moon, and the Kanji tatsu, 龍, dragon.

Configurations on the moon, and enhanced interpretation of a rabbit making mochi.

Mochi-tsuki, 餅搗き, mochi-pound: tsuki, pound, is wordplay on tsuki for moon. The configuration on the moon appears to the Japanese to be a hare pounding mochi, which some call the ‘elixir of life’, in an usu, 臼, mortar, with a kine, 杵, pestle, beneath a katsura, 桂, katsura, cinnamon bark tree. All plants grow in moonlight.

Mochi is glutinous rice steamed and pounded into a mass, divided, and formed into various size balls. These are offered to the god of the moon, Tsuki-yomi, 月読, Moon-read, the brother of Ama-terasu, 天照, Heaven-brightener. Mochi in two settled spheres is offered to Amaterasu at the New Year, which is called kagami mochi, 鏡餅, mirror-mochi.

Mochi-tsuki, 望月, full moon-moon. The Kanji, 望, means full moon, ambition, hope, desire, etc. The word mochi may be written with the Kanji, 持, which means to have, hold, possess, own, use, etc. When applied to mochi / rice cake may refer to rice that is prepared as mochi, which is relatively easy to prepare and eat. Rice, which is a main staple in Japan, must be rinsed, soaked, and boiled or steamed in order to be eaten, which takes a long time, whereas mochi is already cooked, and need only be heated in water or over a fire to be ready to eat.

The reason that mochi is offered to the moon and other deities is complex and controversial.

Tsuki-mi, 月見, moon-see, is looking at the moon, especially the full moon in the eighth lunar month. While looking at the moon, people drink sake, which is made of rice, and catch the moon’s reflection on its surface, and so ‘drink’ the moon.

Sui-getsu, 水月, water-moon, is an extraordinary phrase found in the secular as well and the liturgical world. This is especially true in Buddhism, and Zen in particular. The moon is a prime example of In, 陰, (Chinese Yin) negative, receptive, which is complementary to the sun, which is a prime example of Yō, 陽, (Chinese Yang) positive, penetrative, etc. In truth, the moon is called Tai-In, 太陰, Great-Yin, and the sun is called Tai-Yō, 太陽, Great-Yang.

Suigetsu is a familiar and powerful concept in Asian culture, and especially in Buddhism. Water and the moon are prime examples of the negative or In, 陰, principle. In Buddhism, all is illusion, there is nothing that lasts.

A particular image is one of the thirty-three manifestations of Kannon; Sui–getsu Kan-non, 水月観音, Water-moon See-sound, seated upon a rock, gazing down at the reflection of the moon on the water. Kannon is closely allied with water. Kannon is male, as are most Buddhist deities, but is depicted in female form. Even in very feminine guise, the image often is depicted with a moustache. She carries a lotus upon which one is reborn in her paradise, Fu-da-raku Jō-do, 補陀落浄土, Supply-steep-city Pure-land. Together with Dai-sei-shi Bo-satsu, 大勢至菩薩, Great-strong-attain Sacred tree-buddha, they accompany A-mi-da, 阿弥陀, Praise-increase-steep, the Buddha of Compassion.

In some manifestations, Kannon carries a sui-byō, 水瓶, water-bottle, that contains jō-sui, 浄水, pure-water, and Kan-ro, 甘露, sweet-dew. The vase may hold a willow branch, as in the image of Yō-ryū Kannon, 柳楊, Willow-willow Kannon. The willow is a potent medicine, and Kannon is revered for her healing powers. Kannon is associated with dragon. The dragon is a water creature that brings rain. Seishi has on his crown the same sacred suibyō.

Water is another prime example of In, so that together with the moon, they present a heightened sense of the negative. Curiously, the surface of a body of water acts like a mirror and reflects the image of things such as the moon. Illusion upon illusion. The light of the moon is the reflection of the light of the sun. The sun appears constant, while the moon in its phases appears inconstant, illusory. The sun radiates intense heat, the moon gives off no noticeable heat, but has power over water, and is the cause of the ocean tides. Because the moon influences the sea and tides, and with the image of the hare on the moon, the hare and rabbit are thought to have power over the sea, its tides, and waves.

One of the great enjoyments in Autumn in Japan, is the appreciation of kiku, 菊, chrysanthemum. The kiku is the emblem of the emperor, as its petals radiate outward to infinity in all directions, omnipresence. Kiku-sui, 菊水, chrysanthemum-water. From ancient times it was thought that the chrysanthemum bestowed healthful benefits upon water. Dew drawn from the petals of the chrysanthemum were patted on the skin of the face. A popular brand of sake bears its name.

Autumn is the time of the year when kiku, 菊, chrysanthemums, are on lavish display. Chōyō is one of the Five Festivals of the year, each of which is doubled numbers. First month first day is for everyone, its floral emblem is shō-chiku-bai, 松竹梅, pine-bamboo-‘plum’. Three-three is for girls: momo no se-kku, 桃の節句, peach’s season-passage. Five-five is for boys: Tan-go no se-kku, 端午の節句, Edge-horse’s season-passage, its flower is the shō-bu, 菖蒲, iris-flag. Seven-seven is for lovers, Tanabata, 七夕, Seven-night, the plant emblem is take, 竹, bamboo. Nine-nine is for family with chrysanthemum as its emblem. The chrysanthemum is the emblem of the emperor, and the flower has 16 or more florid with 32 petals that radiate to infinity.

There is, for some, the 11th day of the 11th month, which has the floral emblem of the kiri, 桐, paulownia, which is emblematic of ancestors. The flower of the paulownia is emblematic of the 11th month. It has numerous purple flowers on stalks, and large pods filled with a multitude of seeds. It grows rapidly, and a tree is planted at the birth of a daughter, and when she marries, its wood is cut and made into a chest of drawers.

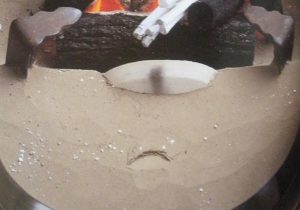

The moon is associated with the do-bu-ro, 土風炉, earthen-wind-hearth, for when building the initial charcoal fire, sho-zumi, 初炭, first-charcoal, the front plane of the ash bed is marred with a tsuki-gata, 月形, moon-shape, cut with a hai-saji, 灰匙, ash-spoon. The ash is let to fall on the back plane of the ash bed. During go–zumi, 後炭, latter-charcoal, re-building the charcoal fire, a small amount of fuji-bai, 藤灰, wisteria-ash, is spooned over the cut in the front of the ash bed. It is said that it is like a cloud passing in front of the moon.

In the most formal presentation of the charcoal fire, the ash bed is covered with many spoonsful of ash that are intended to look like the scales of a fish, uroko-bai, 鱗灰, scale-ash.

Partially hidden in the ash between the upright legs of the go-toku, 五徳, five-virtues, is the mae kawarake, 前土器, fore earth-container.

A mae-kawarake, 前瓦, fore-tile, or, 前土器, fore-earth-container, is placed between the two front talons of the go-toku, 五徳, five-virtues, to deflect the heat of the fire toward the kama, 釜, kettle. Other authorities state that the tile deflects wind from the front opening, hi-mado, 火窓, fire-window.

Still others state that the front opening was originally to empty cinders from the hearth, which is relatively unnecessary when using charcoal. The tile is round and slightly dished, with one small segment removed from the bottom to create a flat edge. This form, when upright, allows some leeway between it and the bottom of the kettle and the bottom of the furo. This tile originated with the shallow saucer kawarake, 土器, earth-container, used in the Shintō service of sacred sake, o-mi-ki, お神酒, hon.-sacred-sake. After the saucer is used for drinking omiki, it is discarded and may become broken, which gives rise to the missing segment of the mae–kawarake. Having the Shintō sake saucer in the furo lends some Shintō sanctity. In modern times, the mae-kawarake is intentionally made with the segment missing.

The kawarake in my collection was retrieved from the refuse pile at I-sei Jin-gu, 伊勢神宮, That-strength God-palace. The saucer has a diameter of san sun kane-jaku, 三寸曲尺, three-sun bend-shaku. The kane shaku equals one linear foot, and is made up of ten sun; one sun is ten bu, and one bu is ten rin. The round mae-kawarake originating in the rites of Shintō may evoke the round aspect of the sun. The sun is personified by Ama-terasu Ō-mi-kami, 天照大御神, Heaven-brightener-great-hon.-god, the supreme deity of Shintō. She is also made manifest in a mirror, kagami. 鏡. Some ancient Japanese mirrors are round, while others are eight-sided. Can the mae-kawarake be identified with the Sun? Perhaps this identification is possible if one considers the ash in the furo being identified with moon.

The crow is featured in one of Japan’s most familiar haiku, that every school child learns:

kare eda ni karasu no tomarikeri aki no kure

枯朶に烏のとまりけり秋の暮

dry branch on crow ’s stopover autumn ’s ending

– Matsu-o Ba-shō, 松尾芭蕉, Pine-tail Banana-plantain

The Ya-ta Garasu, 八咫烏, Eight-span Crow, is a three-legged crow said to have guided Jin-mu Ten-nō, 神武天皇, God-war Heaven-emperor, the first emperor of Japan, from Kuma-no, 熊野, Bear-field, to Yamato, 大和, Great-harmony. The Ya-ta garasu, 八咫烏, Eight-span Crow, is believed to be the messenger of the gods of Kumano. This crow became the emblem of the sun and Ama-terasu, 天照, Heaven-brightener, the sun goddess This mythical black bird has three legs and flies from east to west. There may be some association between the three-legged crow and the go-toku, 五徳, five-virtues, and its three tsume, 爪, talons. Even the Kanji for talon resembles the form of the gotoku trivet. Rikyū wanted to use the gotoku. Kagami bishaku puts furo in the ‘west’. Crow appears, in some depictions, with two legs in front one in back, like the gotoku.

Left: steel te-shoku, 手燭, hand-lamp, candlestick, and iron go–toku, 五徳, five-virtues, trivet for ro, 炉, hearth. Right: same utensils except that the gotoku is inverted. Although the two utensils have similarities, they also have marked differences. The teshoku’s finish is smooth and relatively shiny, and looks new, while the gotoku has a rough, dull, aged surface. When the gotoku is in the hearth, the ring is buried in the ash, the ring of the teshoku is visible and seemingly without purpose. These are aspects of In, 陰, negative, receptive, and Yō, 陽, positive, penetrative, and exhibit aspects of Wabi, 侘, (comparisons), and Sabi, 寂, (loss). When asked to translate wabi and sabi, I respond with wasabi.

The Japanese te-shoku, 手燭, hand-lamp, has three legs, a ring to hold a paper shade, and a pricket for a hollow end candle, ro-soku, 蝋燭, wax-light. Its purpose is to hold a candle, and to be moved, and at night it is carried through the roji, and eventually placed in the tokonoma of the Tearoom. It is black, and with its features, may evoke Amaterasu’s black Ya-ta garasu, 八咫烏, Eight-span crow, which is black and has three legs.

The teshoku is generally used at night, and for a Cha-ji, 茶事, Tea-matter, is placed in the tokonoma during the shō–za, 初座, first-seating, to illuminate the kakemono. During go-za, 後座, latter-seating, it is placed near the hearth to illuminate the Tea proceedings. Illuminating the ‘word’ and the ‘tea’ seems to have a profound and deeper significance. For a Yo-banashi Chaji, 夜咄茶事, Night-talk Tea-matter, flowers are not displayed, but replaced by the plant, seki-shō, 石菖, stone-flag.

In the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, the central element is the tsukubai, 蹲踞, crouch-down, which has a stone basin, chō-zu bachi, 手水鉢, hand-water bowl, for purifying the hands and mouth before entering the Tearoom. Behind the chōzubachi is an ishi dō-rō, 石灯籠, stone light-basket, which establishes the north direction. To the right of the chōzubachi is the te-shoku ishi, 手燭石, hand-lamp stone, that is designated for the candlestick, which is located in the east. On the left side is the yu-oke ishi, 湯桶石, hot water-bucket stone, in the west. Hot water is provided when the weather is very cold.

The iron go-toku, 五徳, five-virtues, is a ring with three legs with turned-in tsume, 爪, talons, and a blackened finish. The above picture on the right, with the ring of the gotoku on top, shows the manner in which the gotoku was originally used to support a cooking pot over a fire. It was Rikyū who turned the gotoku over to have the talons upright to support the kama. It may have been one of the reasons why the furo was changed from the kiri-kake bu-ro, 切掛風炉, cut-hang wind-hearth, which did not need a gotoku to support the kama. It may have been that Rikyū wanted to use a gotoku to emulate the three-legged Ya-ta garasu of Amaterasu. When the teishu takes up the hishaku to ladle hot water, he or she holds the hishaku upright which is called kagami bi-shaku, 鏡柄杓, mirror handle-ladle. The mirror is the sacred emblem of Amaterasu. It may be that Rikyū wanted to evoke the mirror and crow of Amaterasu.

In addition to the manifestation of the mirror, by handling the hishaku, the teishu is metaphorically moved to be in the north. At the beginning of the Tea presentation, the teishu faces north, which is established by the daisu, and the arrangement of the Tea utensils. The mirror ladle moves the teishu to the north, a mirror of the north, which is the seat of deity. With the teishu in the north, the furo on the left is ‘moved’ to the east, and is more closely identified with the location of the Yata Garasu.

It is interesting to note that the ends of the legs of the teshoku turn out, while the talons of the gotoku turn inward. With the gotoku turned over, the talons are upright and the ring is down, opposite the same features as the teshoku. One is meant to be moved, the other is fixed, stable immoveable. The teishu may represent Fudō, 不動, whose name means ‘no-move’. Fudō is depicted seated on a rock set in water, and surrounded by fire.

There are great similarities between Amaterasu Okami and Fudō Myō-ō. Amaterasu is the central deity of Shintō, and although Fudō is one of the lower levels of Buddhist deities, he is a manifestation of Dai-nichi, 大日, Great-sun, the central deity of Buddhism.

The Ya-ta-garasu, 八咫烏, Eight-span-crow, has three legs each with three talons, it is also black and is symbolic of the sun. In Asia, the number three is symbolic of heaven earth and mankind. As symbolic of the sun, the Yatagarasu is also identified with the east, and were an image of the sun/crow be displayed in the tokonoma, it would identify the tokonoma as being in the east, making the Tearoom in the west. The furo as a crow, would locate the furo in the east, so that the charcoal fire dō-zumi, 胴炭, body-charcoal, would have its ‘head’ toward the left or the north.

Te-nugui, 手拭, hand-wipe, white cotton with print text and image of two crows and red circle of the sun, and the name of the shrine; L. 2.8 shaku kane-jaku. Souvenir of Kuma-no Hon-gū Tai-sha, 熊野本宮大社, Bear-field Origin-palace Great-shrine.

Text from right:

I-se ni nana tabi, 伊勢に七度, That-strength to seven-times

Kuma-no mitsu tabi, 熊野に三度, Bear-field to three times

do chi ra ka ke te mo, どちらかけても, either way as well

kata mairi, 片詣り, side (shrine) visit

The pair of crows are Ya-ta Garasu, 八咫烏, Eight-span Crows, flying before the red ‘sun’.

Within the red square is the name of the shrine: Kuma-no Hon-gū Tai-sha, 熊野本宮大社, Bear-field Origin-palace Grand-shrine.

Tenugui are frequent souvenirs of shrines and temples, this one from Kumano Nachi is where there is one of the tallest waterfalls in Japan, and where one might bathe in purification, and need a towel to dry. The main deity of the Kumano shrine is I-za-na-mi no Mikoto, 伊邪那美(の)命,That-wicked-what-beauty of Lady, the primal goddess who created the land and gods of Japan. It is most interesting to note that both Ise and Nachi have women as their main deities.

Kuma-no Na-chi Tai-sha, 熊野那智大社, Bear-field What-wisdom Great-shrine, is one of the great Shintō shrines. The sacred emblem of the shrine is the Ya-ta Garasu, 八咫烏, Eight-span Crow, which is sacred to Amaterasu.

According to the Jū-ni-shi, 十二支, Ten-two-branches, the Asian zodiac, the 9th month is identified with the sign of the Tori, 酉, Cock. The Buddhist guardian of sign of the Tori and the 9th month is Fu-dō Myō-ō, 不動明王, Not-move Bright-king. Fudō is the wrothful manifestation of Dai-nichi Nyo-rai, 大日如来, Great-sun Like-become.

Printed image of Fudō Myō-ō, 不動明王, No-move Bright-king, seated upon a rock in turbulent water. The flame halo behind him, kō-hai, 光背, light-back, is in the stylized shape of bird’s head. It is called Ka-ru-ra-en, 迦楼羅焔, (sound)-tower-spread-flame, as it resembles the wings of a fire deity named Karura. Others identify the bird as a niwatori, 鶏, chicken, and Fudō is the guardian of the sign of the Tori, Chicken. The scroll is from the temple at Nari-ta-san, 成田山, Become-ricefield-mountain.

Fudō is often depicted together with Kan-non Bo-satsu, 観音菩薩, See-sound Grass-buddha, accompanying A-mi-da Nyo-rai, 阿弥陀如来, Praise-increase-steep Like-become. These three deities are metaphorically located in the northwest corner of the yojōhan, which may be seen in the yojōhan diagram.

This bowl was probably made in great numbers for a Buddhist temple. This teabowl is a Japanese adaptation of the Chinese U-san tenmoku, 烏盞天目, crow-cup heaven-eye, one of the seven types of Tenmoku chawan. The term ‘crow’ is intended to mean ‘black’.

The bowl is placed on a three-part keyaki, 欅, zelkova wood dai, 台, support, and because it is often offered to nobility, and to Shintō, Buddhist, and other deities, it is called a ki-nin dai, 貴人台, noble-person support. The dai is based on Chinese models, that are often lacquered black, or with colorful and decorative finishes.

Ten-moku cha-wan, 天目茶碗, heaven-eye tea-bowl, were and are often made for and used by Buddhist temples, for their clergy and visitors. Because the Chinese tea bowls were expensive, they were generally the priority of the wealthy, which are called ki-nin, 貴人, noble-person. In the practice of Chanoyu, there are Tea presentations that are designed to serve nobility called Kinin date, 貴人点, Noble-person offer. Although the tradition uses Tenmoku chawan for kinin, any suitable bowl can be used. After the Tea presentation, the chawan is given to the kinin.

The cha-shaku, 茶杓, tea-scoop, is made of wood from a sacred keyaki, 欅, zelkova, tree at Kuma-no Hon-gū Tai-sha, 熊野本宮大社, Bear-field Origin-palace Great-shrine, and named ‘Hi-ryū’, 飛龍, Flying-dragon, after the sacred waterfall at the shrine. Acquired at the shrine; box stamped, Na-chi Tai-sha, 那智大社, What-wisdom Great-shrine. Although many people may prefer a chashaku made of bamboo, and by a noted Buddhist priest, chashaku are also made of other materials. This chashaku has associations with one Japan’s most important Shintō shrines, which lends some profound spirituality.

The dense, black stone in the Nachi area is famous for its use in making Go-ishi, 碁石, Go-stone, for the 2500 year-old Chinese board game played with white and black stones. The standard Go board has a 19×19 grid of lines, creating 18 x 18 squares. There are 180 white stones and 181 black stones. The stones are placed, alternately, where lines cross, there are 361 intersections. It is curious that the number 18 was prominent in Asia 2500 years ago.