Tea in January and the Willow

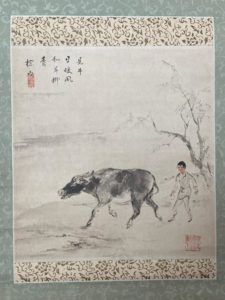

The series depicts the allegorical search for an ox and attaining Buddhist enlightenment, satori, 悟り, understanding. According to the sequence of the Ten Ox Pictures, 3 and 8 refer to before enlightenment and 9 refers to after enlightenment. The river plays a role in the Ten Ox Pictures, and in the brief texts is mentioned and alluded to five times.

The circle of Zen has great interpretations of nothingness. In life, the circle is seen in the sun and moon. The sun is so bright we cannot look at it with the naked eyes, and the circle of the moon is constantly changing. With regard to humans, the circle is found in the eyes, which in Japanese belief were born of the eyes of Izanagi when he bathed after trying to rescue his wife, Izanami, from the underworld.

Left: porcelain plate with painted blue design of a landscape with willow tree, Chinese, early 19th century. Right: ceramic plate with transfer print design of a landscape with willow tree, called Blue Willow pattern, England, late 19th century.

The Blue Willow pattern, developed by Thomas Turner in 1779, eventually became a classic fixture on many tables around the world. The English pattern was based on similar blue landscape designs in Chinese porcelain, and countless interpretations of the Chinese and western patterns produced all manner of objects, made by the thousands of tons. The Chinese products were made for export to the west. The Blue Willow pattern ‘China’ meal service pieces were a fixture in many early Hollywood movies.

Shonzui is the name of a variety of blue and white porcelain, some-tsuke, 染付, dye-attach, that simply has a large amount of blue glaze decoration in the Chinese style. The name Shonzui refers to Go-rō-da-yū Shon-sui, 五郎太夫祥瑞, Five-son-great-spouse Auspicious-congratulatory, who was a Japanese potter who went to China to study the art, and returned to Japan in 1513. After his return he settled in Hi-zen, 肥前, Fertile-fore, western Kyū-shū, 九州, Nine-states, and succeeded in making a ceramic ware decorated in the Chinese fashion with cobalt under the glaze.

The great sea refers to the Buddhist community, sangha, sō-gya, 僧伽, monk/priest-attend, but in nature, Japan has enjoyed the fruits of the sea, including some curious objects. There is a slow-growing, highly regarded coral that from its tree-like appearance is called umi-yanagi, 海柳, sea-willow. It is made into various objects including strings of polished, amber-colored prayer beads, ju-zu, 数珠, number-gems.

The willow in Japanese is yanagi and is written with the Kanji, 柳, which is composed of ki, 木, tree, and u, 卯, hare. The word willow applies to any tree of genus Salix, which includes sallows, poplars, and osiers. ‘Salix’ is derived from the Celtic word ‘sal’ near, and ‘lis’ water, because willows often grow near water. The weeping willow is Salix babylonica. Japanese words for ‘weeping’ willow are shi-dare yanagi, 枝垂柳, branch-hang willow; ito yanagi, 糸柳, thread willow.

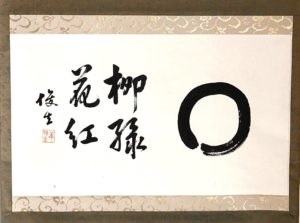

A familiar phrase in Chanoyu is yanagi wa midori hana kurenai, 柳は緑花紅, willow as green flower not bright (red); adapted from the Jū-gyū-zu, 十牛図, Ten-ox-pictures, on the pursuit of understanding, enlightenment.

In Japanese, there are two Kanji for yanagi, willow, yanagi, 柳 and 楊. The Kanji, 柳, is also read ryū, which is borrowed from the Chinese, Liǔ. The Kanji, 楊, is also read yō, refers to the trees willow, poplar, aspen, etc., although the Kanji is used in China primarily for personal names. In Japan, the word for toothpick, yō-ji, uses the Kanji, 楊枝, willow-twig. The Kanji is composed of moku, ki, 木, tree, and yō, 昜, open, sun; which itself is composed of tan, 旦, dawn, and butsu, 勿, not.

In Japanese, the word yanagi means only willow, whereas the word, ryū, has many different Kanji and meanings. The following Kanji that are read ryū, have other readings: tatsu, 竜, dragon, imperial, tatsu, 立, stand up rise, etc, nagare, 流, current, flow, etc. tatsu, 龍, dragon, imperial, etc. The long trailing branches of the weeping willow are likened to serpents, snakes, dragons, eels (unagi), etc.

Weeping willow is called shidare yanagi, 垂柳 , hang-willow, Salix babylonica. The word yanagi means ‘arrow wood/tree,’ as certain willow branches were used to make arrows, but not branches of the weeping willow. There are more than four hundred varieties of willow, in the family Salix. Ao-yanagi, 青柳, green-willow, is one that has budded. A flower bud is a ka-ga, 花芽, or tsubomi, 蕾, bud, a promising young person, etc. Yanagi no tsubomi, 柳の蕾, willow-’s-bud.

The willow originated in China, and was introduced to Japan during the Nara period. In China, arrows were made of willow, which was called in Japanese, ya-no-ki, 矢の木, arrow ’s tree, and later changed to yanagi. There is a curious wordplay on yanagi, ya-na-gi, 八名木, eight-name-three. Names containing yanagi are at times abbreviated to yana, such as Yanagi-bashi, 柳橋, Willow-bridge, becomes Yana-bashi.

The word yana, could be related to the Kanji, 梁, which is read yana and hari. Yana is a weir, ramp-like structure made of bamboo set in a river to catch fish swimming upstream, and hari refers to a joist or crossbeam that supports a ridge pole. The Kanji, 梁木, is read hari-ki, yana-gi, and yana-ki. The ridgepole of San-jū-san-gen-do, 三十三間堂, three-ten-three-interval-hall, is made of willow. The weir and the joist are not wholly dissimilar in structure.

The pussy willow is neko-yanagi, 猫柳, cat-willow, Salix gracilistyla. The fuzzy growths along the stem are one stage of the flower development, and are for obvious reasons called catkins, bi-jō-ka, 尾状花, tail-form-flower. The flowers of different willows are widely varied, and those of weeping willows resemble caterpillars, and usually fall off after blooming. Some regard willows as messy because of the fallen catkins, and in late autumn they lose their dried, dull brassy leaves in abundance.

Authorities cite that the original Kanji for willow is ryū, zakuro, 榴, which now refers to the pomegranate. The left side of the Kanji, 榴, is ki, 木, tree, and the right side was changed from tome, 留, detain, to u, 卯年, hare, which appears to retain the upper part of tome. The hare represents the movement of flowing and stopping, that is inferred by the character of two doors, that open and then shut. Hares are prey, and their habit is to dash and stop still to avoid detection. However, the change of Kanji may have more to do with the willow tree budding at the spring time of the u, 卯, hare.

There is an ancient tale that Ostara, the ancient Germanic goddess of the spring, transformed a bird into a hare, and the hare responded by laying colored eggs for her festival. The Japanese hare of the east accompanies the moon to the west, which is symbolized by the rooster. The rooster follows the sun and rises in the east symbolized by three-legged rooster of Amaterasu.

The sun is Ama-terasu, born of the left eye of Izanagi, and the moon is Tsuku-yomi, 月読, Moon-count, born of the right eye of Izanagi. Izanagi and Izanami were the two young gods chosen to bring order to the world of chaos in Japanese mythology. Izanagi was as tall and as strong as a willow sapling, while Izanami, his consort, was delicate in manner and speech, and as beautiful as the air that filled the High Plain of Heaven. The Lord of Heaven gave Izanagi his legendary spear, Ama-no-nu-boko, 天之瓊矛, Heaven-’s-red jewel-halberd.

In ancient China, when plants were tried and tested to learn if they were edible, the willow tree must have intrigued people. Especially the weeping willow, as it is so different from other trees. The willow is among the very first plants to sprout buds in spring, and a the very last to lose its leaves. It must have been fascinating to observers, who wondered what powers it might have held. The family of willows, genus Salix, contains salicylic acid that relieves pain, and is found in aspirin. The long-trailing branches moving in the wind may have seemed like the flowing of a river, and willows often grow along the sides of rivers.

The willow tree has inspired poets and artists wherever they grow. In temperate climates, the willow is one of the first to bud in spring, and one of the last to lose its leaves even into early winter. Their thin and pliant branches were, and are, used to make baskets. This is evidenced in the etymology: from Old English welig; related to wilige wicker basket, Old Saxon wilgia, Middle High German, wilge, Greek helikē, helix, twisted. The German word for willow is weide; etymology – that which twines, bends, etc.

Although the ‘weeping’ willow has such a fascinating form, of the hundreds of varieties of willow, only a few are ‘weeping’. Sap drips from leaves, which is likened to weeping. The ‘magic’ of the willow is manifest when it moves so gracefully in the wind. Several other species of trees ‘weep’, including shi-dare zakura, 枝垂れ桜, branch-pendulous cherry. The flowers of willows, yanagi no hana, 柳の花, in English called catkins, are often long and slender, and quite different from cherry blossoms. Willows and cherry trees line the rivers in Kyōto, and are also synonymous with the entertainment district.

The willow has so many properties including Salix, that are anti-inflammatory and relieve pain (long known as antirheumatic, analgesic, and antipyretic herbal medicine). In some thought the willow affords a remedy that encourages the positive potential to forgive and forget past injustices and enjoy life, combat negativity, the consequences of resentment, and regain a sense of humor when life presents shortcomings. There is some consideration on the efficacy of the willow and fertility. The Celts identified the ‘month of the willow’, from April 15th to May 12, is represented by willow. In the willow’s spiritual realm is that of the emotions, water, the moon, etc.

The bark of shiro-yanagi, 白柳, white-willow, Salix alba, contains salicin, which is a chemical similar to aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid). This willow medicine has been used in China for centuries. White-willow grows mostly on the banks of rivers and is called the white willow because of the white underside of its leaves. Its wood is excellent for construction and furniture, its branches are used for weaving, its leaves are used as fodder, and it is often grown as an ornamental.

Among the many varieties of willow is the much-loved neko yanagi, 猫柳, cat willow, pussy willow, Salix gracilistyla. Although the plant bears the name willow, yuki yanagi, 雪柳, snow willow, Thunberg spirea, Spirea thunbergii, is unrelated to the willow genus, but is likely likened to the willow because some varieties ‘weep’.

From the author’s name, it appears that the writer was Chinese, and the reading could be suí-liú. The paper mounting is made of momi-gami, 揉紙, rumpled-paper, which is paper that has been painted, and then crumpled, creating a random pattern of wrinkles. This kind of paper is to emulate the painted paper jackets worn by Buddhist priests, that take on a similar appearance after years of wear. Such no-longer wearable paper jackets were treasured and used variously, including as part of the mountings for Buddhist scrolls. As the look of the paper became popular, the supply of disused paper jackets was very limited, so that artists created paper that had a similar appearance. In time, this paper became expensive to acquire.

The calligraphy was possibly written in Kyōto, which helps to identify the source relating to the Ō-baku Shū, 黄檗宗, Yellow-cork Sect of Zen Buddhism. If so, then the writing may have been by a priest at Man-puku-ji, 萬福寺, Ten thousand-fortune-temple, in U-ji, 宇治, Heaven-reign, Kyōto. This was the first Ōbaku Sect temple in Japan. The Chinese style of presenting sen-cha, 煎茶, steeped-tea, was introduced to Japan at this temple that was founded in 1661 by the Chinese priest, Yinyuan Longqi, (Japanese: In-gen Ryū-ki), 隠元隆琦, Conceal-beginning Noble-gemstone. The name ōbaku is taken from the mountain temple’s location in China. Ōbaku, 黄檗, is a kind of herbal medicine present in the obaku berries.

The tree, huáng bò, (Japanese: ō-baku), 黄檗, yellow-amur, is Phellodendron amurense, a species of tree in the family Rutaceae, commonly called the Amur cork tree. It is a major source of huáng bò, one of the fifty fundamental herbs used in traditional Chinese medicine. The Kanji, 檗, is related to a thorny shrub with the Japanese name yanagi-ba ko-baku, 柳叶小檗, willow-‘leaf’ small-cork, Berberis salicaria. Ingen is said to have introduced long, slender string beans, which bear his name, ingen mame, 隠元豆, conceal-origin bean.

Willow trees tend to start to fall apart around 20 years of age. It is possible to have them reach 50 years with proper care. The revered ‘Old Willow’ on Penn State campus fell in 1923 at the age of 64. The oldest black willow ever found in Minnesota was only 85 years old. A weeping willow in Mansfield Ohio is thought to be around 200 years old. So much for averages.

Sacred to the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota is the red willow or polished willow tree, Salix laevigata, that commonly grows along the river ways of the Dakotas, and the inner bark is used for offerings and ceremonial, sacred smoking. In the Lakota and Dakota belief, the ‘Pipe Ceremony in the Stars’ happens each year at sunrise on the Spring Equinox as the Sun, the Red Willow constellation, and the Big Dipper line up along the eastern horizon. The Red Willow is also called the Dried Willow constellation (Triangulum, Aries).

On the vernal equinox, March 20 – 21, the sun rises on the first point of the constellation of Aries. The vernal equinox is when Yin and Yang, In, 陰, negative, and Yō, 陽, positive, are divided in half, so day and night are equal, and winter and summer are equal.

The word yanagi may have origins in the word yana, 梁, (fish) weir, fish trap, because many weirs are made of willow branches: yana-gi, 梁木, weir-tree. The Japanese word for fresh water eel is unagi, 鰻,うなぎ fish that are biologically close to eels, there are conger eels, moray eels, the larva has a transparent, flat willow leaf-like body.

During the New Year presentations of Chanoyu, a long-trailing branch of willow, yanagi, 柳, is held in a length of green bamboo and displayed in the tokonoma. One of the branches is tied around the other branches to form a circle, which is called musubi yanagi, 結柳, tie willow.

One of the many long branches is tied in a loop around all of the other branches, which symbolizes unity such as family ties and the universe. The Kanji musubi, 結 means tie, bind, contract, join, organize, do up hair, fasten, The word musubu, 結ぶ, means to bud such as the budding of the branches in spring. The circle of the loop suggests the moon, the sun, and the mirror of Amaterasu. In some Native American cultures, a dreamcatcher is a handmade red willow hoop, on which is woven a net or web.

A long-trailing willow branch is put into an empty, green bamboo tube, ao-dake zun-dō, 青竹寸胴, green-bamboo measure-body; L. one shaku kane–jaku. It is hung in the back corner of the tokonoma for the first Tea of the New Year. The branch is tied in a loop, musubi-yanagi, 結柳, tie-willow, to represent the unity of life. The willow trees helped to shape the land of Japan, because willow trees were planted along riverbanks to help prevent their flooding. It is curious that the green bamboo tube does not have water in it. Willow branches root very quickly, so that perhaps, the intention is to not give life-giving nourishment to the willow. One of the most famous expressions in Chanoyu is ‘Yanagi wa midori hana kurenai’, 柳緑花紅, willow green flower red.

Corner of a tokonoma, with yanagi kugi, 柳釘, willow nail, black-patinated steel; L. 2 sun kane-jaku.

In the tokonoma, the yanagi kugi, 柳釘, willow nail, should be located in the corner post 5 sun kane-jaku for ko-ma, 小間, small -room, and 7 to 9 sun kane-jaku, for yo-jō-han, 四畳半, four-mat-half, and hiro-ma, 広間, wide-rooms, from the alcove ceiling. The willow hook is under the influence of the trigram for Mountain, Gon, 艮, which also means stopping, northeast and the start of spring. It is also a hypothetical Ki-mon, 鬼門, Demon-gate.

The back wall of the tokonoma is identified with the three months of spring and east. The post in the back left corner of the tokonoma is identified with Ri-sshun, 立春, Start-spring, and from this post hangs the New Year’s musubi yanagi, 結柳, tie-willow. The middle of the back wall is the second month, and the 15th day is the exact center, and the location of the take kugi, 竹釘, bamboo-nail. The 15th day of the 2nd lunar month is Jōdōe and Nehan.

A willow branch is located in the northwest corner of the tokonoma, which is identified with Inu-i, 戌亥, Dog-Boar, also written with the Kanji, 乾. However, when a scroll of the rising sun is displayed in the tokonoma for the New Year, the directions of the tokonoma change. The back wall of the tokonoma changes from the north to the east, the source of the sun. This direction change the corner is identified with the northeast and Ri-sshun, 立春, Spring start, and Ki-mon, 鬼門, Demon-gate, Ko-kū-zō Bo-satsu, 虚空蔵菩薩, Empty-space-keep Grass-buddha, Buddhist guardian of the northeast.

The hanaire may be placed on the floor in the middle of the tokonoma. In addition there are hooks in various locations in the tokonoma for displaying hanaire: toko-bashira, 床柱, bed-post – hana ori–kugi, 花折釘, flower fold-hook; in the center of the back wall of the tokonoma – mu-sō kugi, 無双釘, not-both hook, push in and pull out; ten–jō, 天井, heaven-well – hana hiru-kugi, 花蛭釘, flower-leech hook. The leech is identified with Ebisu, the first-born of Izanagi and Izanami, who could not walk even by the age of three, and was called Hiru-ko, 蛭子, Leech-child. He was put in a boat of camphor wood and set adrift on the Ama-no-kawa, 天の川, Heaven’s River.

The leech hook, hana hiru-kugi, is set into the tokonoma ceiling, which in Japanese is called ten-jō, 天井, heaven-well. The hook looks like a black leech, and is curved like the maga-tama, 勾玉, bent-jewel, one of the three objects of the sacred imperial regalia. Ebisu is one of the Shichi-fuku-jin, 七福神, Seven-fortune-gods, and the only deity whose origins is Japan.

In the back left corner pillar the yanagi kugi, 柳釘, willow hook, is located one shaku below the ceiling, which is for the New Year’s willow branch. It seems remarkable that there is a particular hook for the willow.

The musubi yanagi, 結柳, tie-willow, in the tokonoma has a long-trailing branch that often is accompanied by a cluster of suzu bells on the sanbō. The red and white cord is tied in bows, which is unusual, as the bells have long five-color ribbons attached to the handle. There may be a connection between the bells and the Isuzu-gawa, the bell-river near the sacred shrine of Amaterasu. The sound of wind blowing through the long trailing willow branches makes a sound of rustling paper. Could this be the sound of the suzu bells? Is it the sound of the word suzu? The musubi circle of the willow, is it the yata-kagami? The moon? The spring willow buds are as though to join the stars of the Milky Way. The New Year’s foods, special for many healthful reasons, are eaten with yanagi bashi, 柳箸, willow chopsticks, that should be discarded into a river that flows into the Ama no Gawa, 天の川, River of Heaven, the Milky Way.

In the traditional Japanese Tearoom, light is provided by an oil lamp called a tan-kei, 短檠 , short-lampstand, that is modeled on Chinese bow display stand. The oil, usually na-tane abura, 菜種油, rape-seed oil, is held in a ceramic bowl called a suzume-gawara, 雀瓦, sparrow-tile. Its name is derived from the full rounded form that resembles a stylized fukura suzume, 脹雀, fluffed sparrow.

The bowl is supported on a ceramic dish, shita kawara-ke, 下土器, down earth-plate, that rests on a metal ring attached to the upright post. On the supporting box, is another dish, shita-zara, 下皿, down-dish, that catches drips, also called an abura-zara, 油皿, oil-dish.

To provide light, wicks, tō-shin, 灯芯, lamp-wick, are made of the pith of tatami grass, i-gusa, 藺草, rush-grass. These wicks are long, and when lit, the wick is not consumed, as the oil is simply carried to through the wick. The wicks are gathered together and one of the wicks is loosely tied around the bunch to form a circle, musubi, 結び, knot. Musubi also means to unite as well as to bud as a leaf or flower. The willow branch is alive and is identified with water, which is In, and the lamp wicks are dead, burning, and identified with Yō.

The tankei that was preferred by Sen no Rikyū is red-glazed Raku yaki, 楽焼, Pleasure fired. The oil bowl is called suzume/sparrow, and a red sparrow may be called su-jaku, 朱雀, red-sparrow. Sujaku and/or Suzaku is the name of the southern quadrant of the Asian astrological heavens. Each quadrant is identified with mythical creatures called Shi-jin, 四神, Four-gods: Sei-ryū, 青龍, Green-dragon, Byak-ko, 白虎, White-tiger, and Gen-bu, 玄武, Black-warrior. In Asia, there are twenty-eight constellations, so that each quadrant is composed of seven constellations.

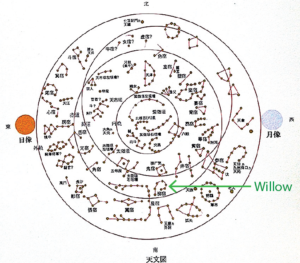

In a four and a half-tatami room, the number of wicks is seven. I believe that the wicks represent the seven constellations in each quadrant. One of the constellations of the Sujaku, Red-sparrow, quadrant of the heavens is named Ryū, 柳, Willow. The constellations of the Sujaku group are named Well, Demon, Willow, Star, Net, Wing, and Chariot.

Su-zaku, 朱雀, Vermilion-sparrow, is described as a red bird that resembles a pheasant with a five-colored plumage and is perpetually covered in flames. The tankei, with its fire light and association with the fiery Suzaku, is appropriately placed near the hearth.

When researching the tankei and the suzume gawara, I sensed a relationship between the tōshin, wicks, of the tankei and the musubi yanagi of the New Year. Both have a loop in them. The willow has a long willow branch made into a loop to encircle the other branches, and one of the long wicks is made into a loop to encircle the others. One of the seven constellations of the sky quadrant, Su-zaku, 朱雀, Red-bird, is Yanagi, 柳, Willow. Are the wicks of the tankei a representation of the Ama no Gawa?

Suzaku is part of the western constellation of Hydra, which is a water snake, and is the largest of all the constellations. In depictions of the hydra snake, the creature is shown with a coil or loop in its body. Could there be a connection between the Hydra/Willow constellation, the New Year willow and the tankei loop in the wicks? In Asian thought, the circle is the symbol for water, which is represented as a sphere in the Go-rin-tō, 五輪塔, Five-ring-tower. The circle is In, 陰, negative, receptive, the straight is Yō, 陽, positive, penetrative. The oil, like water, is In, and the fire is Yō.

Nuriko-boshi, ぬりこ星, Willow-star, also Nuriko-boshi, Ryū–shuku, Yanagi-juku, 柳宿, Willow-mansion, one of the Asian 28 constellations called mansions. In the western vocabulary, the constellation is in Hydra. The Willow constellation, composed of 8 stars, is one of the 7 constellations in the south quadrant of the heavens called Su-zaku, 朱雀, Red-sparrow, in which the Willow constellation is the beak of the bird.

From the southeast corner of the yojōhan tearoom toward the west, are the constellations of the I, 井, Well, Oni, 鬼, Demon, Yanagi, 柳, Willow, Hoshi, 星, Star. These are in the same location as the nijiri-guchi, 躙口, crawl in-opening, to the yojōhan Tearoom. If the red sparrow tankei is identified with the south, perhaps the location of the tied willow is also metaphorically identified with the south. The constellation of the Willow is slightly east of due south, a sort of mirror reflection of the tied willow in the tokonoma, slightly east of due north.

The tankei is used at night to provide light, just as the night sky is filled with stars. I believe the suzume gawara and its seven wicks represent the southern Suzaku quadrant and its seven constellations. The tankei is placed to the ‘north’ of the ro, and is identified with the Suzaku which metaphorically establishes the south direction. The tankei in the ‘south’ locates the guests in the west which emulates Amida’s Jō-do, 浄土, Pure-land.

Drawing of sho-in kazari, 書院飾り, write-institute display, depicting various utensils used in calligraphy, and other implements. Included is a mirror hanging on a hook in one of the supporting posts, which may prompt questioning as to its purpose at a writing desk. The mirror is associated with the moon as well as the sun of Amaterasu. Note the vase-like pitcher containing a willow branch. The willow is also strongly associated with the moon and water, which are both the essence of In, 陰, negative-receptive. It is interesting to note the relationship of the moon and water to calligraphy and how ink is made, mixed, and used.

Drawing of sho-in kazari, 書院飾り, write-institute display, depicting various utensils used in calligraphy, and other implements. Included is a mirror hanging on a hook in one of the supporting posts, which may prompt questioning as to its purpose at a writing desk. The mirror is associated with the moon as well as the sun of Amaterasu. Note the vase-like pitcher containing a willow branch. The willow is also strongly associated with the moon and water, which are both the essence of In, 陰, negative-receptive. It is interesting to note the relationship of the moon and water to calligraphy and how ink is made, mixed, and used.

The willow is closely associated with Kannon, as one of her 33 manifestations is the Yō-ryū Kannon, 楊柳観音, Weeping willow-willow Sound-see. Kannon, with her willow branch, sprinkles the divine nectar of life, compassion, and wisdom, which is held in the bottle, upon the devotees as to bless them with physical and spiritual peace. The willow branch is also a symbol of being able to bend (or adapt) but not break. The willow is also used in shamanistic rituals and has had medicinal purposes as well.

Tan-zaku, 短冊, short-volume, with a painting of a branch of yanagi, 柳, willow; L. 12 sun kane-jaku, by Ue-shima Masaki, 植島まさき, Plant-island Masaki, Kyōto. Mounted temporarily on a tan-zaku kake, 短冊掛, short-volume hanger, sugi, 杉, cedar, and take, 竹, bamboo; L. 20 sun kane-jaku.

Kake-mono, 掛物, hang-thing, with picture with calligraphy that had been removed from a shikishi and mounted as a hanging scroll. The picture is of a boy, an ox, and a willow tree, with the calligraphy: ‘Ken-gyū’, 見牛, See-ox, Nichi-dan fu-wa kishi yanagi-ao, 日暖風和岸柳青, sun-warm wind harmonious shore willow-green, from picture 3 of the Jū-gyū-zu, 十牛図, Ten-ox-pictures. Stamps illegible. There is a familiar adage: yanagi ni kaze, 柳に風, willow in wind, handling things without making waves; taking in one’s stride.

According to tradition, there are things that a Buddhist may have, the Bi-ku Jū-hachi-motsu, 比丘十八物, Compare-hill Ten-eight-things. The first one of the Eighteen Things a Buddhist monk may have is a willow toothpick.

楊枝, 歯をみがくとき使用する.

Yō-ji, ha o mi-ga-ku to-ki shi-yō-suru.

Willow-branch, use when brushing teeth.

Toothpicks in former times were made of small twigs of willow, yanagi, 楊, as the willow has healthful benefits. A toothpick is an essential possession of a Buddhist monk. The piece is decorated with a gold-leaf design of a sprig of nan-ten, 南天, south-heaven, nandina: the word nanten is wordplay on nan-ten, 難転, difficulty-turn around.

About the origins of the name of Buddhist monks called Sha-mon, 沙門, Sand-gate – one source called them ‘wandering monks’. Also, Buddhist priests are called Sō–mon, 桑門, Mulberry-gate. Buddha said that his followers would be in numbers equal to the sands of the Ganges River. In ancient China, a mulberry tree should not be planted in front of a dwelling-house, nor a willow at the back, because sang, mulberry, has the same sound as sang, sorrow, and the willow being symbolic of frailty and lust, may exercise an unhealthy influence on the ladies who generally occupy the rear apartments. “A Buddhist monk does not spend more than three nights under the same mulberry tree, for fear of emotional attachment.”

The toko-bashira is located in the middle of the north wall of the yojōhan. This location in the center of the north is identified with the sign of Ne, 子, Rat, and Sen-ju Kan-non Bo-satsu, 千手観音菩薩, Thousand-hand See-world Grass-buddha.

The post in the back left corner of the tokonoma is where a yanagi-kugi, 柳釘, willow hook, is placed near the ceiling to hang an ao-dake zun-dō, 青竹寸胴, green-bamboo measure-body to hold the musubi yanagi, 結柳 , tie-willow. The willow is identified with Kannon, Yō-ryū Kan-non, 楊柳観音, Willow-willow Kannon. Willow Kannon also holds a sui-byō, 水瓶, water-bottle, that contains kan-ro, 甘露, sweet-dew, the Buddhist elixir of life. This vessel may be identified with the hana-ire, flower-container, that hangs from the ori-kugi, 折釘, flower-fold-hook, in the side of the tokobashira.

In Japanese culture, women are likened to the willow, and men are likened to bamboo. In the willow display, the willow is put into the bamboo, so that the willow is identified with the positive aspect of Yō, 陽, masculine. The bamboo is a container, which is identified as In, 陰, feminine.

Senju Kannon Bosatsu is one of the 33 manifestations of Kannon, and the main object of worship at San-jū-san-gen-dō, 三十三間堂, Three-ten-three-interval-hall, in Kyōto. The muna-gi, 棟木, ridgepole-wood, of the structure is made of willow wood. Sculpture of Buddhist deities are at times made of willow. Because of its molecular structure, willow wood does not readily split.

The origin of the building of Sanjūsangendō came through a dream had by Emperor Go-shira-kawa, whose headaches he believed were dispelled by the Yanagi no Sei, 柳の精, Willow’ s Spirit.

Willows flourish alongside of water, especially rivers. Spirits as little lights fall from the weeping willow into the flowing stream that wends its way to the sea, and eventually to the Ama-no-gawa, 天の川, Heaven’s-river, the Milky Way.

The weeping willow, Salix Babylonica bears the name which came from its perceived origin in Babylon cited in the Judeo-Christian Bible.

In Psalm 137: “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.”

The Hebrew word for willow is arab, which comes from a root word meaning to braid as in wattle and daub construction.

The ancient Hebrew for harp is nebel, which may refer to the lyre. The portable instrument was made of cypress or sandalwood with 10 or more gut strings, that was plucked with the fingers, and struck with a little stick. Its form is the subject of great debate. Its form may come from key words in the Psalm, hung up our lyres. The weight of the lyres caused the willow branches to droop. This act seems unlikely if the willow branches were already drooping, so the Israelites willow must not have been of the weeping sort. Their ‘lyre’ willow became the weeping willow, in Babylon. As it happens, the tree was not the ‘weeping’ or not willow, but a kind of poplar; the Euphrates poplar, Populus euphratica, with willow-like leaves on long, drooping shoots.

The Kanji yanagi, 柳, willow, Salix babylonica, is composed of moku, 木, tree, and u, 卯, mortise, rabbit. It is one of 12 branches, meaning early morning, east, 6 am, sunrise, and originated in human and animal sacrifice cut in half letting the blood flow, hence ‘weeping’, and association with death, mourning. U-no-hana, 卯の花, hare’s-flower, is so named because it blooms in U-zuki, 卯月, Hare-month.

Hi-shaku, 柄杓, handle-ladle, bamboo, for fu-ro, 風炉, wind-hearth; with the furo, the hishaku is handled with references to handling a bow and arrow: yumi, 弓, bow, ya, 矢, arrow. Oki bi-shaku, 置き柄杓, place (arrow), kiri bi-shaku, 切柄杓, cut (release arrow, pictured), hiki bi-shaku, 引き柄杓, draw (bow).

At the beginning of a Tea presentation, the hishaku is handled by the teishu in such a manner that is likened to a mirror: kagami bi-shaku, 鏡柄杓, mirror handle-ladle. The hishaku is held upright so that the cup of the ladle is in front of and parallel to the heart. The mirror is for the heart, not the face.

There is an unspoken reference to the connection between the mirror, which is sacred to Shintō and Taoism, and the arrow, which is also deemed sacred to some beliefs.

There is the ha-ma yumi, 破魔弓, defeat-evil spirit bow, which is a ceremonial bow used to drive off evil. Such arrows, adorned with other charms, are sold at Shintō shrines for the New Year as amulets to dispel evil. In addition, there is the Yō-kyū, 楊弓, willow-bow, about 7 kane-jaku long, and made of willow wood.

There is an archery contest called Toshi-ya, 通し矢, through-arrow, that is held annually in mid-January, at San-jū-san-gen-dō, 三十三間堂, Three-ten-three-interval-hall, Kyōto. The willow is sacred at Sanjūsangendō, where sacred water is sprinkled with a willow branch, for health bestowed by Kannon, the principal image of the temple.

Japanese things made of willow wood include yanagi ge-ta, 柳下駄, willow down-burden, low clogs made of willow wood. Wooden geta are worn primarily when it rains or snow, or in their aftermath of puddles.

Geta have many forms and styles, however, they are made of a variety of wood, rectangular for men and oval for women, and are raised on two cross pieces that are called teeth, ge-ta no ha, 下駄の歯, down-burden’s tooth. Geta are often made of a single piece of wood, as with koma ge-ta, 駒下駄, colt down-burden, low wooden clogs made of a single piece of wood, or three pieces; sole and two separate ‘teeth’. There are geta with only one tooth, which are made for increasing the wearer’s strength and balance. There are also geta made of metal, again for increasing strength and discipline.

For Chanoyu, special geta made of aka-sugi, 赤杉, red-cedar, are worn in the ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground, garden of a Teahouse. Rikyū believed that geta should be worn in the roji because the ground is wet, however, he felt that zori should be worn, because people didn’t know how to walk properly wearing wooden geta.

The strap that holds the geta to the foot is called a hana-o, 鼻緒, nose-strap. The strap is made of straw, leather, fabric, plastic, etc. In the world of Chanoyu, the hana-o is white. The strap or thong is secured by three holes cut into the sole plate; one toward the toes and two at the sides. The front strap goes between the big and second two. Curiously, regarding the three holes – one hole is forward, and could be regarded as shō-men, 正面, correct-face, the front.

The impression that geta leave in snow or mud resembles the number two, ni, 二, and an equal sign, 〓. Coincidentally, the two lines resemble the two lines that form the divination sign of Tai-Yō, 太陽, Great-Yang, of the Eki-kyō, 易経, Change-sutra. In number symbolism, the number 2 is In, negative, as it can be divided equally in half, and the number 3 is Yō, positive, as its cannot be equally divided.

A popular card game is Hana-fuda, 花札, flower-cards, which has 4 cards in 12 suits that are identified with the 12 months of the year. The cards have designs of plants, flowers, etc. of each suit. The suit of Yanagi, 柳, Willow, is identified with the 11th month. Depicted in the first card on the left is the Heian calligrapher poet, O-no no Tō-fū, 小野道風, Little-field Way-wind, in the rain. The suit is also called Ame, 雨, Rain, suit. He was dis-spirited about his calligraphy, and saw a frog trying in vain to leap onto a willow branch. Finally, the frog succeeded in getting on the branch, which encouraged the poet to try more diligently in his art. Note the stream, which is where willow trees grow. The second card has a tsubame, 燕, swallow, the third has a blank tan-zaku, 短冊, short-volume, and the fourth is the dramatic lightning card, Oni-fuda, 鬼札, Demon-card. The standard pattern of the modern hanafuda, is called Hachi-hachi-bana, 八八花, eight-eight-flowers.

Ha-go-ita, 羽子板, feather-of-board, often made of kiri, 桐, paulownia; 8.5 x 2.4 sun kujira-jaku, hane, 羽, feather, 2.5 sun kujira-jaku, equipment used in the game ha-ne–tsuki, 羽根突き, feather-root thrust.

During the New Year festivities, some Japanese people play a kind of shuttlecock and battledore game called ha-ne–tsuki, 羽根突き, feather-root thrust. Two players use a wooden paddle, ha-go-ita, 羽子板, feather-of-board, to strike a hane, 羽, feather, and to keep it from falling to the ground. The hane is made of a soapberry seed and bird feathers. The play originated at Shintō shrines during the Nara period. It is thought that batting the ‘ball’ at a shrine drives away evil spirits. World history is filled with the activity of hitting something with a stick: baseball, tennis, ping-pong, hockey, stickball, etc.

The game of cricket, which is thought to have begun in Britain long ago, and now popular around the world is played with a flat bat that is used to hit a ball to strike a wooden stake. The bat is made of willow wood that is produced in England and called English willow. Willow wood also comes from India, Pakistan, and elsewhere, and is called Kashmir willow. English willow is quite white wood, and Kashmir willow is darker. Some bats are made of other woods including teak and saal. Cricket bats are available in lengths for children to adults which has a maximum length of 34 3/8 inches. The various measurements with fractions seem arbitrary, when compared to traditional Japanese measurements. The measurement of 34 3/8 transposed to kane-jaku, is 2.8 shaku, which falls within the Japanese tradition of including the number 8. This is not to conclude that the cricket bat originated in Japan. However, why the cricket’s bat fractioned lengths?

The lawn game of croquet is believed to have been first played by 13th century French peasants, who used simple wooden mallets to hit wooden balls through hoops made of willow branches stuck in the ground.

Traditionally, the gift was mochi in the form of small balls. Mochi-dama, 餅玉, mochi-jewel, are small balls of mochi left white and often some are colored pink, and may include other colors.

These balls that are also called mochi-bana, 餅花, mochi-flowers, are attached to willow branches especially for Ko-shō-gatsu, 小正月, Little-correct-month, called Little New Year is a festival held during the 14th to the 16th of the New Year. Originally, Koshōgatsu was held according to the old calendar on the full moon of the first lunar month. After the Lunar New Year is over, in some areas of the country, the mochibana are roasted and eaten, to ensure good health for the entire year. Yaki-mochi, 焼き餅, fired-mochi has been enjoyed in Japan for centuries.

A variation of putting mochi balls on willow branches is the tradition of putting the mochi on upright branches of giant dogwood called mizu-ki dan-go, 水木団子, water-tree round-of, dogwood mochi balls. Mizuki is identified as Cornus controversa. The origin of the Japanese name comes from the sap that comes out like water, mizu, when the branches of the tree, ki, are cut. The colors of some mizuki dango represent the four seasons: red for spring cherry blossoms, green for summer plants, yellow for autumn foliage, and white for winter snow. The black drupes of cornus controversa are very bitter and sour, and are not eaten by humans, but are eaten by birds that disperse the seeds. The flowers of the mizuki are tiny off-white clusters on branches that are in layered tiers, unlike the showy, large four-petal crosses of common dogwood.

Mochi dumplings are attached to the branches of a kind of dogwood tree, and called Dan-go no ki, 団子の木, round-of ’s tree. This dogwood tree grows on the water edge, and absorbs water as well. The buds of a dogwood tree come out facing upwards. Therefore, it also contains a wish that good fortune will arise. In addition, since it is a tree that grows quickly, there is also a wish that children will grow up quickly.

The mochi decoration also may include mayu, 繭, (silk) cocoon, that are also dyed pink and white, kō-haku, 紅白, red-white. These may be real mayu, or mochi in the form of a cocoon. In the past, many people raised silkworms to make cocoons used in the silk industry. The willow’s mochi bana display was to ensure a bountiful harvest of mulberry leaves to feed the worms, and for an abundant rice crop. Traditionally, the branch of mochi-bana is put into a green bamboo tube. This willow is very like the musubi yanagi displayed in the tokonoma for the New Year. The word musubi, 結び, also refers to triangular, cooked rice balls wrapped in nori. Perhaps, the mochi bana willow is to represent the blooming of the buds on the musubi yanagi. The loop in the musubi yanagi is absent with the mochibana willow. The word musubu, 結ぶ, means to bud, bear fruit, etc. The triangular rice musubi is to emulate the shape of the sacred mountain to which it is offered.

After eating the New Year’s food, the yanagi bashi are discarded into a river. It is curious to note that mochi that is attached to willow branches for the New Year, and is eaten with willow branches at the end of the New Year festivities.

Willow water, is plain water in which willow twigs are steeped to be infused with auxin hormone that increases plant root growth. Willow water is made by placing about a cup of willow twigs the diameter of a pencil, and one inch long, in around a half-gallon of water, bringing to a boil, and letting them steep for 24 to 48 hours. The twigs are removed, the water is cooled and used at once or stored in a sealed container in the refrigerator.

In the above drawing of the shoin kazari, a willow branch is put into a pitcher, that is ostensibly filled with water. One might wonder for what purpose. Perhaps the willow water is used to wet the suzuri, 硯, inkstone, which is located nearby. Why willow water?

Yanagi no mizu, 柳の水, willow ’s water, is the name of an ancient well in Kyōto. The well is located near San-jō, 三条, Three-article [street], and Nishi-no-tō-in, 西洞院, West-cave-institute, on the site of a 12th century imperial palace, and later the mansion of Oda Nobunaga’s son. Sen no Rikyū drew the well’s clear, icy water for preparing Tea. The well is so highly prized, that the surrounding area is named Ryū-sui-chō, 柳水町, Willow-water-town. Other important places in the near vicinity include Hon-nō-ji, 本能寺, True-ability-temple, and Ro-kkaku-dō, 六角堂, Six-corner-hall, which are closely associated with Oda Nobunaga.

Japanese calligraphy is done with sumi, 墨, ink, and a fude, 筆, brush, on kami, 紙, paper. Traditional Japanese ink is made of susu, 煤, soot, from plant oil including na-tane abura, 菜種油, rape-seed oil, and animal glue, formed and dried to a stick or paste. Soot is often taken from the underside of the roof-like element of an ishi dō-rō, 石灯籠, stone lamp-basket. Although plain water is used to make the ink, sometimes tsuyu, 露, dew is gathered from lotus leaves or other leaves.

Characters are written with the dew-made ink. Ink and calligraphy are curious aspects of In, 陰, negative, receptive, and Yō, 陽, positive, penetrative. The oil as a liquid is In, and when burning, the fire is Yō. The soot is dry – Yō. Ink is made with water – In. After the ink is used to write or draw, it dries – Yō. The teishu reads the writing aloud, although science can identify sound as having some physical aspect, the sound, incorporeal, exists only in time and space and therefore is Yō.

Perhaps the cutting and displaying a willow branch in the tokonoma for the New Year, has something to do with pruning a willow tree. In Japanese, tree and plant pruning is sen-tei suru, 剪定する, clip-determine to do. For willows, pruning should be done while the tree is dormant, in either early winter or very early spring before catkins appear and any growth begins. This is around the time when the willow is cut for the New Year display. In former times, the New Year would be later in January or early February. Pruning will produce much regrowth, and getting rid of old, damaged, dead, or crossing branches helps to increase sunlight and air flow.

Tsuma yō-ji Sei-taku, 爪楊枝贅沢, claw willow-branch Luxury-swamp, translated as Toothpick indulgence. On the third Sunday in January, is the most important memorial service at temple of San-jū-san-gen-dō, 三十三間堂, Three-ten-three-interval-hall, which is said to have a tradition dating back to the Heian period, introduced from India. In the ceremony, the sacred waters of the willows, which are considered sacred trees, are touched with a wet willow stick, or sprinkled onto the worshipers to pray for Kannon. The rite is believed to be particularly effective against headaches.

During purification rituals that have Kannon as the central deity, willow leaves are dipped in ‘sanctified’ water, and sprinkled to purify people and places. This is similar to the aspergillum, holy water sprinkler, used from ancient times in Judeo Christian rites. There are many origins of the aspergillum, including a wooden handle to which is tied branches of hyssop. The identity of ‘hyssop’ is also obscured by time, although it is thought to be a kind of mint-like herb that has healing properties. There are similar properties found in the sacred Shintō bells, suzu, 鈴, used for purification in shrines.

Yanagi sumi, 柳炭, willow charcoal; artists’ charcoal drawing sticks made from willow twigs; lengths vary although a standard is about 5 inches, 4.2 sun kane-jaku, the same length as furo eda-zumi, 枝炭, branch-charcoal, made from tsutsuji, 躑躅, azalea twigs.

Kō-gō, 香合, incense-gather, porcelain, covered container in the form of a 9-scallop ball with a tiny figure of an usagi, 兎, hare, with geometric patterns in some-tsuke, 染付, dye-attach, blue and white, in the style of Shon–zui, 祥瑞, Auspicious-congratulatory, Kiyo-mizu yaki, 清水焼, Pure-water fired, by Taka-no Shō-a-mi, 高野昭阿弥, High-field Shine-praise-increase; diam. 2 sun kane-jaku.

2023 is an U-doshi, 卯年, Hare-year; Mizunoto-U, 癸卯, Water’s younger brother Hare, which is also read ki–bō.