Tea in May

The cha-ire, 茶入, tea-receptacle, is made of brown tō–ki, 陶器, ceramic-container, in the form of shiri-bukura, 尻膨, bottom-swell, with mottled, glossy brown glaze, Kyō yaki, 京焼, Capital fired, by Ima-shiro Sato, 今城聡, Now-castle Wise, Ryū-ki gama, 龍㐂窯, Dragon-joy kiln, Kyōto. The chaire is a copy of ‘I-yo Sudare’, 伊予簾, That-previous Blinds, with zō–ge buta, 象牙蓋, elephant-tusk [ivory] lid, and multi-colored striped silk bag, shi-fuku, 仕覆, work-cover, with pattern of ‘I-yo Sudare don–su,’ 伊予簾緞子, That-previous Blinds damask-of.

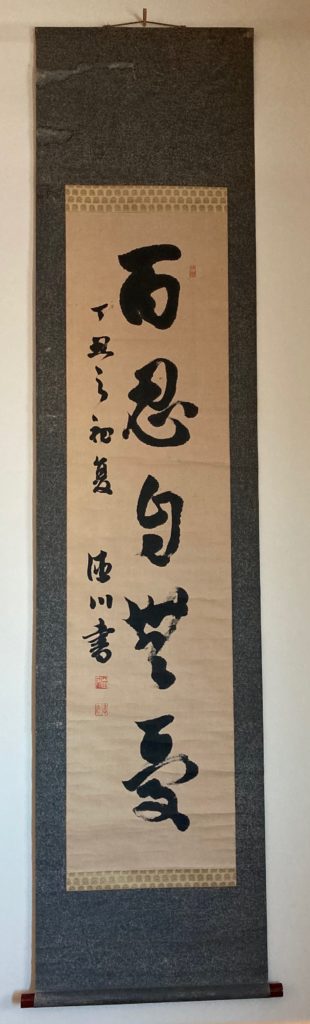

Many years ago, this chashaku was a gift from the proprietor of a Cha-dō-gu-ya, 茶道具屋, Tea-way-tool-house, in Gi-on, 祇園, God-garden, in Kyōto. He told me that it was in the style of En-nō-sai, 円能斎, Circle-art-abstain, XIII Iemoto of Urasenke. Years ago, when I was leaving Japan, I used the chashaku during a Cha-ji, 茶事, Tea-matter, and asked my first teacher and guest, Mori Akiko Sensei, to give it a go-mei, 御銘, hon.-name. She chose ‘Funa-de’, 船出, Boat-out, which means a ferryboat that leaves, but returns. I returned.

Although swords are never allowed in the Tearoom, several Tea masters have used the word for sword, ken, for the pointed tip of the chashaku, which ordinarily is called tsuyu, 露, dew. I have always felt that ‘dew’ was the traces of tea left on the tip of the chashaku. The Buddhist elixir of immortality is called kan-ro, 甘露, sweet-dew, and the Tea garden is called a ro-ji, 露地, dew-ground. The Kanji for dew, 露, also means enlightenment, satori, 悟り.

Gin-kaku-ji, 銀閣寺, Silver-pavilion-temple, was created by Ashi-kaga Yoshi-masa, 足利義政, Foot-benefit Righteous-government, in part, for the veneration of Kannon in the Ginkaku itself, and for Amida in the Tōgudō.

In 1988, I acquired this chawan at Ginkakuji as omiyage, お土産, hon.-earth-product, after I lead a group of Midorikai students on a tour of the Tō-gu-dō, 東求堂, East-request-hall.

A raku, 楽, pleasure, teabowl is not thrown on a wheel, but the clay is formed by hand to roughly form a bowl. It is allowed to age to a leather stage, and then carved by hand using metal and wood tools, some of which resemble a bamboo Tea scoop to finish the shape. It is bisque-fired, covered with glaze, black for example, and fired for a short period of time. When creating a red glaze or other type, after the bisque firing, and glaze firing, a clear glaze is applied and fired again. Depending on the artist, the bowl is fired for three to six hours. It is taken with a self-made pair of forceps red-hot from the kiln, and left to cool in the air. True Raku wares that are taken live from the kiln are not put into anything, such a water or wood chips. Only pieces made by the Ta-naka, 田中, Ricefield-middle, family of Raku potters are true ‘raku’, and they have kept various techniques secret for sixteen generations. While the bowl cools, it makes a tiny pinging sound. It should be remembered that the Kanji, raku, 楽, also means ‘music’.

The quince flowers in late April early May, and although they may have an irresistible beauty, their nearly lethal thorns render them most inappropriate for cha-bana, 茶花, tea-flower. In Kyōto, at Go-ō Jin-ja, 護王神社, Guard-king God-shrine, there is an old sacred quince tree, and the juice made from its fruit is said to alleviate symptoms of asthma. Quince is one of my family names.

For further study, see also: Go-Gatsu, April in Japan: Following Elephants, May: Still Following Elephants